The Quebec Court of Appeal Recognizes Certain Powers

advertisement

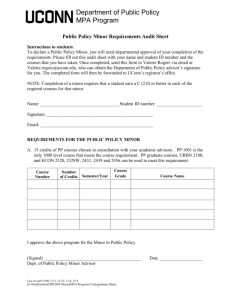

August 2014 Commercial Real Estate Bulletin The Quebec Court of Appeal Recognizes Certain Powers of Municipalities with respect to the Location of Radiocommunications Towers On May 30, 2014, the Quebec Court of Appeal rendered judgment regarding several appeals from a decision made by the Superior Court on 2 July 2013. In doing so, the Court of Appeal found that the municipality of Châteauguay was acting within its powers when it issued a notice of land reserve that in effect prevented Rogers from installing a radiocommunications tower at a particular address for which Industry Canada had granted authorization, where that authorization also permitted construction at an alternative site. Facts Rogers Communications Inc. (“Rogers”) is a Canadian corporation that controls and manages a wireless communications network. In Autumn of 2007, Rogers undertook a survey of the Châteauguay area with an view to finding propitious locations for the installation of a new wireless communications tower, in order to fill existing gaps in its network coverage. In December 2007, Rogers negotiated a lease with the owner of 411 St-Francis for the installation of a tower. In March 2008, Rogers advised Châteauguay of its intention to install a new tower at 411 St-Francis, a process that requires a 120day public consultation as specified in the Industry Canada circular. Rogers also published a notice in a local newspaper and sent a letter to each resident and property owner within a designated area surrounding the proposed tower. McMillan LLP Vancouver Calgary Toronto Ottawa Montréal Hong Kong mcmillan.ca Page 2 On April 28 2008, Châteauguay informed Rogers that it opposed the project, giving as reason the lack of conformity to applicable zoning regulations, the unappealing aesthetic of such installations, and fears for the safety and health of nearby residents. Châteauguay proposed that Rogers add a new tower at an existing installation or augment one of its existing towers with a stronger signal, or build its new tower at another location, 50 Industriel. Rogers responded on 28 August 2008, arguing that the existing sites were inadequate and that 50 Industriel was unavailable. Rogers assured Châteauguay that the tower would comply with Health Canada’s edict on exposure limits to radiofrequency electromagnetic energy, Safety Code 6.1 Châteauguay, despite reiterating its disagreement with Rogers, delivered a permit for construction at 411 St-Francis in February 2009. Following a petition by Châteauguay’s citizens, further consultation and various discussions took place in September of 2009, following which Industry Canada advised Châteauguay and Rogers that the public consultation had been completed to its satisfaction and that the project would have no negative impact on the environment. Industry Canada also advised, however, that it would prefer Châteauguay and Rogers to agree on a site, and would not render a final decision on the dossier until Châteauguay had had an opportunity to find an alternative site. Rogers and Châteauguay attempted to find an alternative site and eventually settled on 50 Industriel. The owners of that property were negotiating its sale when Rogers and Châteauguay approached them and they expressed little interest in dealing with Rogers, leaving 411 St-Francis as the only effective alternative. It should be noted that both the 50 Industriel and the 411 St-Francis sites were located within the research area designated by Rogers for the purpose of erecting its new tower. Rogers agreed to consider the alternative site at 50 Industriel if Châteauguay could complete an acquisition (by expropriation or private agreement) within 60 days from December 15, 2009. Châteauguay adopted a resolution to expropriate the site on January 18, 2010, but in the meantime, Ms. Christine White had acquired the property from the previous owners. Châteauguay moved ahead with the expropriation, publishing the notice in the land register on February17, 2010 -- outside the 60-day period required by Rogers. 1 See “Safety Code 6: Health Canada's Radiofrequency Exposure Guidelines”, online: < www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ewhsemt/pubs/radiation/radio_guide-lignes_direct/index-eng.php >. McMillan LLP mcmillan.ca Page 3 On March 8, 2010, Ms. White deposited a motion challenging Châteauguay’s notice of expropriation. After several months and considerable discussion among Industry Canada, Châteauguay, and Rogers, Industry Canada granted Rogers permission to proceed with the installation of a new tower at 411 St-Francis; Rogers advised Châteauguay of its intent to proceed. Châteauguay continued to request that Rogers install its new tower at 50 Industriel, if its expropriation turned out to be successful. Châteauguay promised not to contest Rogers’ moving forward with the installation at 411 St-Francis if the municipality lost to Mme White’s challenge. Rogers rejected Châteauguay’s offer, and on October 12, 2010, Châteauguay served a notice of land reserve in respect of 411 St-Francis. On October 27, 2010, Rogers filed a motion to contest the notice. The notice was renewed October 2, 2012. First Instance Decision Relying on Spraytech,2 the trial judge concluded that Châteauguay had exercised its power of expropriation at 50 Industriel with a view to protecting the well-being of its citizens, and had not done so abusively or to favour a private enterprise. The judge also concluded that the expropriation had purpose, since Rogers’ refusal of the offer to build at 50 Industriel was not definitive. Châteauguay’s actions did not trench on federal powers either, since there was no obligation upon Rogers to use 50 Industriel. However, while recognizing Châteauguay’s right under the Cities and Towns Act3 to take possession of buildings for purposes of creating a land reserve, the judge concluded that in the case of 411 St-Francis, Châteauguay acted in bad faith: its only goal was to prevent Rogers from constructing a tower. He concluded, in consequence, that the reserve taken by Châteauguay on 411 StFrancis was null. All three parties appealed. 2 114957 Canada Ltée (Spraytech, Société d'arrosage) v. Hudson (Town), 2001 SCC 40 [“Spraytech”]. 3 Cities and Towns Act, CQLR c C-19. McMillan LLP mcmillan.ca Page 4 The Appeal Rogers contended that the notices of expropriation and reserve were unconstitutional and that the trial judge erred in allowing the expert evidence on the safety of electromagnetic fields. On the opposite, Châteauguay argued that the judge erred in finding that Châteauguay had acted in bad faith and abused its power. Lastly, Ms. White asked the Court to assess whether the expropriation order at 50 Industriel was made without object, given that Rogers no longer wished to install its tower at that location. In a nutshell, the Court had to determine whether the municipality had the right to take steps, in the particular circumstances of this case, to influence the location of the tower within the designated area determined by Rogers. The Constitutional Questions (a) True Nature (Pith and Substance) The Court noted that the constitutional issue amounted to whether the true nature of Châteauguay’s notices of expropriation and reserve, taken together, were ultra vires, trenching on the federal radiocommunications power. To that end, the issue was whether Châteauguay acted in service of legitimate municipal purposes. The Court of Appeal invoked the application of constitutional doctrines raised by the Supreme Court of Canada in Canadian Western Bank,4 noting the Court’s favouring of the doctrines of pith and substance, double aspect, and federal paramountcy over the notion of interjurisdictional immunity. The Court of Appeal also called on the notion of cooperative federalism endorsed in PHS Community Services,5 stating that the modern tendency is to find a just balance between the two orders of government. The Court noted that Châteauguay’s expropriation of 50 Industriel, a site for Rogers’ installation that would have the least impact, was motivated by the goals of protecting the well-being of citizens and the harmonious organization of the municipal territory. The Court also noted that these were both legitimate municipal goals, sharing the view of the trial judge that the power of expropriation may be exercised by a municipality in service of the well-being of citizens. In this case, the municipality was unable to find conclusive evidence showing the harmlessness of electromagnetic fields of the type 4 Canadian Western Bank v. Alberta, 2007 SCC 22 [“Canadian Western Bank”]. 5 Canada (Attorney General) v. PHS Community Services Society, 2011 SCC 44 [“PHS Community Services”]. McMillan LLP mcmillan.ca Page 5 generated by Rogers’ equipment. In order to address the concerns of citizens regarding their health, whether the concerns were wellfounded or not, Châteauguay was within its rights to put an end to a controversy that was creating uneasiness by expropriating 50 Industriel. The Court disagreed with the trial judge, however, as to the finding of bad faith on the part of Châteauguay with respect to the notice of reserve. The Court noted that the trial judge had recognized that Châteauguay’s goal in making the notice of reserve was in service of the well-being of the citizens, which is a legitimate municipal purpose. Without putting such a notice in place, all of Châteauguay’s efforts in creating an alternative for Rogers at 50 Industriel would have been in vain. In consequence, the Court concluded that Châteauguay acted in the interests of its citizens and for legitimate municipal goals, and that the true nature of the notices taken together did not trench on federal competence. (b) Interjurisdictional Immunity The Court also held that, contrary to Rogers’ pleadings, there was no precedent for applying the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity to the specific placement of radiocommunications antennae within an area already found suitable. The Court noted that the Privy Council determined in Bell6 that municipal councils had a voice in determining the placement of telephone poles, concluding that the placement of radiocommunications towers was not an indivisible core element of the federal radiocommunications power suitable for the application of interjurisdictional immunity. (c) Federal Paramountcy The Court of Appeal also concluded that there was no reason to apply the doctrine of federal paramountcy in the instant case. In its reasons, the Court spelled out the two forms of conflict that can lead to the application of paramountcy: a conflict of application between federal and provincial law, or a conflict arising where a provincial law frustrates the purpose of a federal law. The Court found no conflict of application, stating that Industry Canada’s authorization allowing Rogers to build a new tower permitted construction at either of 411 St-Francis or 50 Industriel. It was possible, therefore, for Rogers to comply both with the 6 Toronto Corporation v. Bell Telephone Co. of Canada, [1905] A.C. 52 (C.P.) [“Bell”]. McMillan LLP mcmillan.ca Page 6 federal authorization and the requirements of Châteauguay regarding the placement of the tower within the relevant area. The Court also found no conflict arising from frustration of federal purpose. The Court described the purpose of the Radiocommunication Act7 as permitting the deployment of radiocommunication networks while respecting the needs of local populations. In addition, the Court remarked that Châteauguay’s purpose in respect of the expropriation and reserve notices was to protect the well-being of its citizens and the harmonious development of its territory, both objectives that can be attained without frustrating a federal purpose. Here, Châteauguay did not prevent the installation of Rogers’ tower altogether, but merely designated an alternative location. Conclusion The Court of Appeal has confirmed certain powers conferred on municipalities to self-determine the development of their territories and to protect the well-being of their citizens, despite the federal nature of radiocommunications towers and the issuance of authorizations by the federal government. The threshold for the demonstration of bad faith and abuse of power in expropriation and issuance of land reserve notices is a high one and the onus is on the expropriated. Consequently, according to the Court of Appeal’s reasoning, it is difficult for one to successfully argue that a municipality’s decision to relocate a proposed tower is null by reason of abuse of right or bad faith, especially in the presence of a legitimate municipal purpose. Unlike aerodromes,8 in certain circumstances, the location of a radiocommunications tower does not constitute an essential and indivisible core of a federal power. Therefore, a municipality does not necessarily infringe on federal jurisdiction by merely requiring a tower to be erected at a different location on its territory, where such additional location is located within the research area of the telecommunications company. by Stéphanie Hamelin and Pierre-Christian Collins Hoffman 7 Radiocommunication Act, R.S.C. 1985, c R-2. 8 Quebec (Attorney General) v. Canadian Owners and Pilots Association, 2010 SCC 39. McMillan LLP mcmillan.ca Page 7 For more information on this topic please contact: Montréal Stéphanie Hamelin 514.987.5085 stephanie.hamelin@mcmillan.ca Montréal Pierre-Christian Collins 514.987.5062 pierre-christian.hoffman@mcmillan.ca Hoffman a cautionary note The foregoing provides only an overview and does not constitute legal advice. Readers are cautioned against making any decisions based on this material alone. Rather, specific legal advice should be obtained. © McMillan LLP 2014 McMillan LLP mcmillan.ca