Untitled - Academic Journal of Southeast Asian Studies

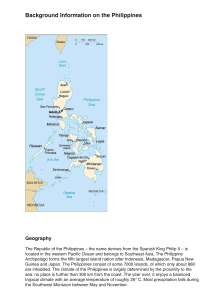

advertisement