Before the Opium Wars

advertisement

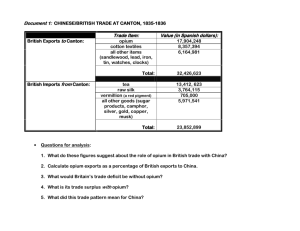

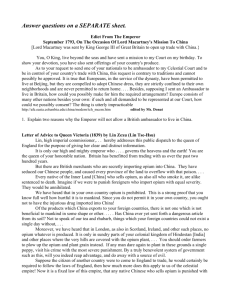

Table of Contents Before the Opium Wars.................................................................................................... 3 Trading System ............................................................................................................. 3 Opium ............................................................................................................................ 5 Rising Tensions ............................................................................................................. 5 Pre-Opium War China ..................................................................................................... 7 Silver and British Demand for Tea ............................................................................. 7 Charter Act and Napier Affair .................................................................................... 7 Key Players ........................................................................................................................ 8 Works Cited..................................................................................................................... 10 2 Before the Opium Wars Trading System Though China was considered a closed country until the 19th century, the British had been trading goods with tributary system at the ports of Zhoushan, Xiamen, and Canton since 1635. After the 1680s, about four decades after the start of the Qing dynasty, China relaxed maritime trade restrictions by legalizing foreign trade. Though this may have appeared to the world that China was becoming more open, the Qing’s original intention of legalizing foreign trade was to increase profit from taxation on trade and Chinese oversea voyages. With legal permission, trade expanded with Britain, United States, Turkey, India, and Southeast Asia. Most trade occurred with the English, Dutch, and French East India Companies. These trade agreements seemed like they would flourish into established relationships. However, the Qing Emperor issued a decree in 1757 to explicitly limit foreign trade to one port in Canton. Despite the restrictions, British fascination with the products from China prompted Great Britain to become one of the biggest trading partners. The Chinese established the “Canton System” from 1700-1842, during which foreign maritime trade flourished at the port in Guangdong (formally known as Canton). There were three major trading establishments within the Canton System: the Chinese trade with the rest of southeast Asia; the “country” trade in which goods from other countries, such as India, were used as currency by some Europeans; and lastly, “China trade” between Europe and China. Within China, merchants established firms to monopolize trade at the port. The westerners knew each merchant firm as a “cohong,” also known as “hong” to the native Chinese. Merchants that paid the Emperor to monopolize their power regulated each firm. Though merchants were given the sole trading rights, they also were responsible for any debts and the accommodations for their trading partners. The firms were responsible for each foreign ship that arrived and the traders aboard the ships. The cohong had the liberty to determine prices, collect duties, and levy fees on foreign traders. Accordingly, foreign merchants were under Chinese jurisdiction when trading at the Canton port. Foreign merchants were not allowed to interact with local residents nor learn Chinese for communication with those other than the cohong. Both parties agreed on this simplified convention of communication called pidgin. This was a type of verbal communication formally used to conduct trade between foreigners and Chinese. Moreover, foreigners who arrived to trade had to land in Macao and take a separate river trip with Chinese transportation to 3 the final harbor. The only location in which the foreigners were allowed to reside was the Thirteen Factories district (so named because of its thirteen resident housing warehouses). No permanent residency was allowed, and foreigners were only permitted to reside in the warehouses from March to November of each year. Furthermore, no extraterritorial agreement was settled, so all infractions by foreigners were tried through the Chinese judiciary system. Other regulations also prohibited foreign warships, firearms, and women. Despite these reductions in freedom for the merchants, trade continued, as European countries still desired Chinese merchandise. On the British end, the East India Company was responsible for all the British ships and traders that engaged in trade in Canton. The Chinese and British governments were not involved as the intermediary merchant groups handled the trades themselves. As such, no formal diplomatic relationships were established between China and the Western countries with which it traded. As a result of British fascination with Chinese goods, the British sought Chinese tea, rhubarb, silk, spices, and porcelain. In exchange, the Chinese were only satisfied with silver as payment. Products made in China were advanced compared to the British goods and made in abundance. As the Chinese had no need for the British goods, they saw no value in the manufactured goods the British offered to trade. Tea exports grew from 92,000 pounds in 1700 to 2.7 million pounds in 1751. By 1800, the East India Company was trading 23 million pounds of tea annually for 2.6 million pounds of silver. Silver was hard to acquire as the British had to seek other countries for supply. In desperation to continue trade with China, the British started to import opium illegally instead of silver. In 1793, a British statesman Lord George Macartney journeyed to the Chinese capital of Peking (present-day Beijing) to expand trade and reduce the isolationistic regulations the Chinese established. Sir George Staunton and Staunton’s son, a linguistic genius, accompanied Macartney. Once Macartney and his associates were granted permission to speak with Emperor Qianlong, Staunton’s son spoke with the officials in fluent Chinese. Macartney brought many gifts, including Europe’s latest astronomy technology, along with a letter from King George III. The letter asked the Emperor to add a position called British Resident Minister in Beijing. This would initiate trade and a political alliance between Britain and China. After a few days, the Emperor declined the addition of such a British position as this would incite extraterritorial disputes. Macartney then attempted to negotiate with the court to open more ports, but to no avail. He also failed to abide by Chinese cultural customs, specifically the kowtow, where one bows his head to the ground to show respect. This offence proved to be unfavorable for his negotiations. In 1816, Lord Amherst tried to accomplish the same goals as Macartney, again without success. 4 Another major event in Sino-English relations was the Napier Affair, which occurred in 1834. During the affair, Lord William John Napier attempted to decrease the restrictions of the Canton System through negotiations at Macao. However, Napier failed to alleviate any of the harsh regulations due to his lack of diplomacy and proper communication. Napier attempted negotiate with the governor-general of Liangguang, Lu Kun, but he was not even given the opportunity to meet the governor-general in person. With no progress and increasing tension, Napier resorted to military tactics that resulted in fatalities on both sides. The skirmish ended in a stalemate, and Napier was forced to retreat due to his deteriorating health. Thus, the strict restrictions imposed by the Chinese sparked initial tensions between the British and Chinese. Opium Turkish and Arab traders first introduced opium as a medicinal ingredient in the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD). However, by the 15th century, opium was mixed with tobacco and smoked recreationally. In time, opium dens were established so that it could be smoked socially, but this leisure activity eventually had a detrimental impact on society. Addicts resorted to selling personal possessions in order to feed the habit. By 1729, Emperor Yongzheng banned the sale and the smoking of opium given its addictiveness and negative personal consequences. Nevertheless, opium legalization was an ongoing debate even after the ban. India, Bengal, and other regions under the British East India Company also produced opium. The Portuguese were the first to discover the profit of selling opium to China. Later, by 1773, the British monopolized the opium cultivation and used this opium to trade for Chinese tea in place of the diminishing supply of silver. Because of the ban, the British imported opium through “country traders” or private licensed traders. Smugglers along the coast of China illegally imported the opium from the country traders. To aid the smuggling, a network of corrupt officials efficiently distributed the product throughout China. By the end of the 18th century, the British traded over six million pounds of tea annually from Canton by the trade of opium, not silver. In 1834, the monopoly was passed on to private entrepreneurs, and the newborn competition decreased prices of opium and increased sales. By 1836, China received thirty thousand chests (1 chest = 140 pounds) of opium from India annually through British trade. The British managed to increase earnings from China despite the lack of silver. 5 Rising Tensions In 1838, the British were selling around 1400 tons of opium annually while the Chinese government sentenced all opium traffickers to death. Lin Zexu was appointed as the Special Imperial Commissioner in 1839, in hopes of eradicating all opium trade in Canton. His role was to enforce the opium ban. Lin accomplished two goals successfully: Lin effectively forced addicts to be treated off the drug and punished domestic drug dealers. Lin also attempted to enforce the ban of opium sales, confiscate supplies, and force foreigners to sign a “no opium trade” agreement. However, these three regulations incited conflicts between the Chinese and the British. The British prospered from the illegal business to addicts. This act was seen as a major infringement of the Chinese laws and disrespect to the Emperor. In addition to the conflict Lin caused with the opium ban regulations, tensions were already building up as Western countries implored China to open up more ports and further expand trading. China’s isolationistic policies did not alleviate the tension. Also, British ships started exploring further north, causing unease amongst the Chinese. Furthermore, missionaries started arriving with Christian teachings, which only exacerbated Chinese hostility toward foreigners. Finally, extraterritoriality became an impending issue as the British pushed their influence beyond trade. The simulation will begin in January of 1836. Any events in history occurring after this date will not have taken place yet. Delegates representing the leaders of China and Britain will respond to domestic and international crises that arise from the rising tension brought on by the opium ban while promoting his or her self-interests, as well. The key issues and delegate roles in the Chinese party are summarized below. Extensive research beyond this background will be necessary to fully present each delegate’s portfolio with accuracy. 6 Pre-Opium War China China committee will comprise of delegates taking on various roles as representatives of the Qing government. Use this topic guide as backgrounder to the important issues that can be debated during committee session. This is not a research report, nor a source that should be referenced during debate. Additional sources and links have been provided at the end of this guide to help you with your research and understanding of this topic. Silver and British Demand for Tea Silver was the only accepted method of payment for goods in China. Britain’s gold standard meant that silver had to be purchased from other countries to pay for Chinese goods, which were in high demand. One good in particular, tea, contributed to Britain’s large trade deficits. As attempts to negotiate better trade terms and access to China all failed, the British decided to counter-trade opium of Indian origin. Opium destined for China was grown in India under a British East India Company monopoly. British traders bought and shipped auctioned opium to China. The opium trade with India was profitable and reversed the flow of silver. Charter Act and Napier Affair The Charter Act of 1833 ended the British East India Company’s monopoly on the opium trade with China. New sources of opium increased competition, which led Lord William John Napier to attempt the establishment of a direct relationship with the Viceroy of Canton. Because direct contact with Chinese officials was banned under the Canton System, the Viceroy of Canton refused Lord Napier’s attempt, which forced the British to accept the loss of the opium trade monopoly by the British East India Company. 7 Key Players Lin Zexu – An imperial commissioner sent to halt and confiscate the illegal importation of opium by the British. Lin used force to confiscate, destroy, and ban the sale of opium. Huang Juezi – A scholar-official and petitioner to the Daoguang Emperor to stop the opium trade. Tao Zhu – A scholar-official who championed open market principles to end the Qing salt monopoly in order to stem the outflow of silver due to the opium trade. Daoguang Emperor (chair) – The eighth Emperor of the Qing dynasty who presided over the First Opium War and massive increase in the inflows of opium during his reign. Keying – Official who negotiated the Treaty of Nanking and subsequent unequal treaties of Whampoa, Wanghia, and Canton. Howqua – The leader of the Canton Cohong who oversaw the growth of Canton and accompanying trade prosperity. Prince Gong (Yixin) – A prince in the Qing Dynasty who campaigned for friendly relations between China and Western powers. Ye Mingchen – A Qing official and governor of Guangdong noted for his resistance to British forces and demands. Sengge Rinchen – A Qing general of Mongol heritage who was in charge of the fighting the British and French invasion in China. Qishan – A Qing official of Manchu heritage tasked to negotiate peace with the British by Lin Zexu. Guan Tianpei – The commander of Chinese naval forces in the First Opium War. Yishan – A military commander tasked to defend Guangzhou against invading British troops. 8 Yijing – A Qing prince of Manchu heritage who served as a military officer in the First Opium War. Yang Fang – A Qing military general and diplomat opposed to peace negotiations advocated by Qishan. 9 Works Cited Allingham, Philip. "England and China: The Opium Wars, 1839-60." The Victorian Web. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Sept. 2014. <http://www.victorianweb.org/history/empire/opiumwars/opiumwars1.html>. "China Trade and the East India Company." China Trade and the East India Company. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelpregion/asia/china/guidesources/chinatrade/>. "Historical Collections Exhibit." After the Opium War: Treaty Ports and Compradors. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/heard/treaty-ports-compradors.html>. "List Of First Opium War Battles." Ranker. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Sept. 2014. <http://www.ranker.com/list/list-of-first-opium-war-battles/reference>. "MIT Visualizing Cultures." MIT Visualizing Cultures. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/opium_wars_01/ow1_essay01.html>. "Opium in China - The Downfall of Imperial China - HistoryWiz." Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.historywiz.com/downfall.htm>. "Opium Wars." Opium Wars. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www2.uhv.edu/fairlambh/asian/opium_wars.htm>. "[Regents Prep Global History] Imperialism: China." Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.regentsprep.org/Regents/global/themes/imperialism/china.cfm>. Szczepanski, Kallie. "The First and Second Opium Wars." About.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Sept. 2014. <http://asianhistory.about.com/od/colonialisminasia/ss/China-Opium-Wars_2.htm>. "The Canton System of Trade." By Ralph Heymsfeld. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.thepeacefulsea.com/canton-system.html>. 10 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Canton System (Chinese History)." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/93224/Canton-system>. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Opium Trade (British and Chinese History)." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/430160/opium-trade>. "The Old China Trade: Before 1842." Penobscot Marine Museum. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.penobscotmarinemuseum.org/pbho-1/maine-and-orient/old-china-trade1842>. "The Opening to China Part I: The First Opium War, the United States, and the Treaty of Wangxia, 1839–1844 - 1830–1860 - Milestones - Office of the Historian." Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <https://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/china-1>. "The Opium War and Foreign Encroachment | Asia for Educators." Columbia University. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Sept. 2014. <http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/china_1750_opium.htm>. "1856 - 1860 - Second Opium War - The Late Qing - Jianshixue." 1856 - 1860 - Second Opium War - The Late Qing - Jianshixue. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://xiaoshixue.squarespace.com/the-late-qing/1856-1860-second-opium-war.html>. 11