Pay Modernisation: A new contract for NHS consultants in England

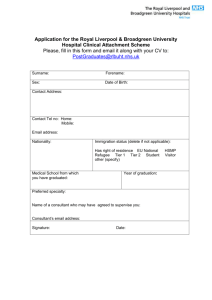

advertisement