Robin Osborne, “Law, the Democratic Citizen and the

advertisement

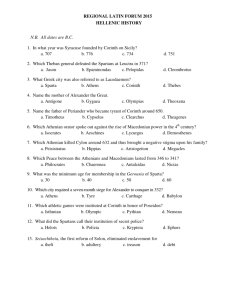

Law, the Democratic Citizen and the Representation of Women in Classical Athens Robin Osborne Past and Present, No. 155. (May, 1997), pp. 3-33. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-2746%28199705%290%3A155%3C3%3ALTDCAT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Past and Present is currently published by Oxford University Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oup.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. http://www.jstor.org Sun Dec 2 17:57:21 2007 LAW, THE DEMOCRATIC CITIZEN AND THE REPRESENTATION O F WOMEN IN CLASSICAL ATHENS* Do new laws actually bring about social change? Or do they simply reflect changes that have already taken place informally? Greek political analysts were prone to assume that laws do change things. The first half of the account of the Athenian constitution written as part of an Aristotelian research project in the 320s B.C. structures its history of the development of the constitution according to a series of moments of reform.' Modern historians of Athens have followed this example, with only rare attempts to highlight the continuities uninterrupted by apparently reforming legislation.' More recently cynicism has set in as historians have argued that many, if not all, legal changes in classical Athens simply confirmed what had already become established pra~tice.~ In this article I look at one particular law, passed in the middle of the fifth century B.C., which changed the formal qualification for Athenian citizenship to insistence upon descent from an Athenian mother as well as an Athenian father. In the first section of the article I review the evidence for the law and the possible reasons for passing it. I argue that there is a strong sense in which the law did merely reflect the possessive and exclusive attitude towards Athenian citizenship which had already developed as Athens acquired, and increasingly imposed her rule upon, the * I first explored these ideas at a conference, 'Democratie athenienne et culture' in Athens in 1992, and later developed them in a lecture at Trinity College Dublin. I am grateful to the participants in the discussions on both occasions, and to Karen Stears and Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood for helping me to turn the ideas into this article. 'See the summary [Aristotle], Constitution of the Athenians, 41. See, for example, the chapter divisions of C. Hignett, A History of the Athenian Constitution to the End of the FiJth Century B.C. (Oxford, 1952). A clear, if trivial, example of this is provided by the law which made the Ionic alphabet (which included eta and omega) Athens' official script, rather than the Attic alphabet: Theopompos, 115 F155, in Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker, ed. F. Jacoby, 16 vols. in 3 pts (Berlin and Leiden, 1923- ). Inscriptions show that Ionic letters had been increasingly employed by official stonecutters years before the law was brought in. 4 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 tribute-paying Aegean allies of what we call 'the Athenian empire' in the years after the Persian Wars. I suggest that the evidence for any marked effect on Athenian marriage patterns is so scant that we would be wise to regard the law as bringing about only limited changes in the situation with which it directly concerned itself. In the second section, however, I argue that the law did have important consequences, which the Athenians themselves were unlikely to have foreseen: the law changed not who became the wives of Athenian citizens, but how Athenian citizens thought of their wives in particular, and of their families more generally. In arguing this I will base my case not, primarily, on literary sources, but on sculpted funerary monuments. I suggest that the transformation of funerary monuments from displaying only men to regularly and most prominently displaying women is best understood not in terms of artistic development, nor in terms of attitudes to death, but in terms of women's newly important place in citizen identity. The law's insistence that citizens have Athenian mothers led to men advertising both their mothers and their wives in the only place where the public display of a respectable woman was acceptable: in the cemetery. The display of women led to the display of men in a domestic context, and I suggest that by doing so it appreciably altered the agenda for masculinity and redefined which aspects of life were politically relevant, moving the boundary between public and private life. In the course of this enquiry I hope to reveal some of the ways that political and social life were mutually implicated in classical Athens, and to show how archaeological material can illuminate even political aspects of Athenian history. I PERIKLES' CITIZENSHIP LAW AND ITS CONTEXT In 45110 B.C. the Athenians passed a measure, proposed by Perikles, to limit citizenship to those freeborn persons whose mothers, as well as fathers, were Athenian. This law is mentioned by a number of ancient sources, but only the report in the Aristotelian Constitution of the Athenians (26.4) attempts to explain why such a law was passed: 'because of the number of citizen^'.^ P. J. Rhodes, A Commentary on the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeta (Oxford, 1981; repr. with selected addenda, 1993), 331-5, 775, admirably summarizes both ancient evidence and modern scholarship. LAW AND THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN ATHENS 5 Although a recent study has attempted to show that there was indeed a rapid increase in the number of Athenian citizens in the decades immediately before the passage of the law,5 the Aristotelian explanation seems unlikely to have been based on any accurate knowledge of Athenian demographic history. In Politics (1276a26-34), written before the Constitution of the Athenian~,~ Aristotle posits the general rule that cities define citizenship generously when short of men, strictly when citizen numbers are buoyant: the explanation of Perikles' Law in the Constitution of the Athenians may simply be an application of this rule.7 That the Athenian citizen population grew abnormally fast between 500 and 430 B.C. is not in itself improbable, but population growth is an inadequate explanation of Perikles' Citizenship Law. Our best evidence for Athenian citizen numbers in the fifth century comes from Thucydides' account (2.13) of Athenian human resources at the outbreak of the war with Sparta in 432 B.C. A. W. Gomme long ago calculated a citizen population of 47,000 on the basis of these figures; M. H. Hansen has more recently suggested that the figures would be compatible with a citizen population as high as 60,000.8 Neither figure seems very plausible for the citizen population seventy years earlier in 500 B.C., particularly if the infantry numbers at Marathon in 490 B.C. (9,000 or 10,000)9 are compared to those given for 432 B.C. (13,000, 'not counting the oldest and youngest'). A growth-rate of about one per cent per annum during the first half of the fifth century seems quite probable. That Perikles' Law was seen to relate to population is suggested by its suspension during the Peloponnesian War, when taking more than one wife seems to have been legally permitted in order to maintain or increase C. Patterson, Perikles' Citizenship Lau' of451-0 B.C. (New York, 1981). Rhodes, Corn~tlentaryon the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeia, 58-61. ' Ibid., 333. As Rhodes points out, Perikles' Law does not conform to Aristotle's other 'rule' in Politics (1319b6-ll), that democracies strengthen the popular classes by being generous with citizenship. A. W. Gomme, The Population of Athens in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries B.C. (Oxford, 1933); M. H. Hansen, 'Athenian Population Losses 431-403 B.C. and the Number of Athenian Citizens in 431 B.C.', in M. H. Hansen (ed.), Three Studies in Athenian De~tlography(Historisk-filosopfiske Meddelelser, lvi, Copenhagen, 1988). See also Thucydides. History I I , ed. with trans. and commentary P. J. Rhodes (Warminster, 1988), 271-7. 9,000 Nepos, Miltiades 5.1; 10,000 Justin 11.9. Cf. Herodotos 9.28.6 and Plutarch Aristeides 11.1: 8,000 Athenians at Plataia in 479 B.C. 6 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 citizen numbers. But insistence on both parents being Athenian would have only affected the citizen population if either men with no Athenian parent or with only a n Athenian mother had previously been accepted as citizens, or if female infanticide in Attica was prevalent enough to mean that after the law was passed there were insufficient Athenian women to provide all Athenian men with wives. Neither suggestion is plausible as a description of what was, or was believed by Athenians to be, the situation in Athens. lo If Perikles' Citizenship Law was not occasioned by a concern with population, what did motivate it? Some modern scholars have held that the motivation was narrowly political: Perikles' political opponents included men whose mothers andlor wives were not Athenian, most notably the general Kimon." Since Kimon himself may well have died while serving as Athenian general in 451 B.c.," and since those sons of Kimon who may have been born of a marriage to an Arkadian woman retained Athenian citizenship (Perikles' Law seems not to have been retrospective, as its re-enactment in 40312 B.C. certainly was not), the facts tell heavily against such an explanation. l 3 More commonly, scholars have taken the law to be antiaristocratic. Marriages to foreign women seem to have been particularly prominent among the Athenian elite, who established their status outside their own citv and their claims on valuable material resources elsewhere by these links with families in other Greek cities. Herodotos tells the story (6.126-31) of Kleisthenes, the sixth-century tyrant of Sikyon, who married his daughter Agariste to the Athenian Megakles after holding a year-long international competition between suitors. Other fathers were not in a position to scrutinize prospective bridegrooms so closely, but numerous examples of elite marriages across political boundaries can be traced.14 Perikles' own mother, Agariste, was the granddaughter of the Sikyonian Agariste after whom she was named. lo Cf. D. Ogden, Greek Bastardy in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods (Oxford, 1996), 64-9. l 1 Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker, pt 3b (supplement), i, 477-81. l 2 On the date of death of Kimon, see R. Meiggs, The Athenian Empire (Oxford, 1972), 124-8. l 3 J. K. Davies, Athenian Propertied Families (Oxford, 1971), 302-5. l4 L. Gernet, 'The Marriages of Tyrants', in L. Gernet (ed.), The Arrthropologj~of Ancient Greece (Baltimore, 1981; J.-P. Vernant, 'Marriage', in J.-P. Vernant (ed.), Myth and Society in Ancient Greece (Brighton, 1980). I discuss Vernant's views further below. LAW AND THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN ATHENS 7 But if such marriages were common in the years before the Persians Wars, and non-existent after Perikles' Law was passed, was it Perikles' Law that caused the change? While it is not difficult to find examples of Athenian men marrying foreign women in the years down to 480 B.C., examples of such marriages after 480 are lacking. Since we are in general not well informed about the identity of wives, the argument from silence is not strong, but a change in marriage patterns in the early fifth century would not be difficult to understand. Foreign birth and treachery are two of the allegations which Athenians scrawled on the potsherds they used to ostracize individual politicians for ten years (a procedure first used in 487 B.C.), and prominent foreign links are one of the features that link the various men known to have been ostracized in the following quarter century. Calling on foreign friends for help had been employed in the sixth century by Peisistratos to establish himself as tyrant at Athens, by the Alkmaionidai in their attempts to dislodge the Peisistratid tyranny, and by the political opponent of the democratic reformer Kleisthenes in his attempts to block those reforms. It would not be surprising if Athenians as a whole were suspicious of the foreign connections of members of the elite. Renouncing foreign brides gave members of the Athenian elite the opportunity to continue showing off on the international circuit, while also claiming that they did so not for personal glory, but for the glory of Athens. Athenians in the sixth century who competed for honour in the playgrounds of the grand panHellenic festivals, converted athletic success into direct personal material advantage by exchanging its symbolic capital for a good marriage. In the fifth century, Athenians could reasonably maintain, as Alkibiades is famously made to do in Thucydides (6.16.2), that athletic victories brought as much honour to the city of origin as to the individual. The belief that the Athenian elite may have grown markedly less keen on foreign marriages quite independently of Perikles' Citizenship Law is reinforced by increased Athenian sensitivity about links of 'ritualized friendship' with men in other cities, links which were quite unaffected by legislation. Gabriel Herman has shown how the cross-polis links which guest-friendship involved came to be seen as potentially subversive to the interests of the city, and how official state friendships in the form of proxenies, which did not themselves promote the individual 8 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 1.55 interests of particular wealthy Athenians, were promoted as an alternative means of maintaining friendly contact with other cities.15 Perikles himself shows a sensitivity to Athenian suspicion of the political implications of guest-friendships when he offers to make over his property to the city in the event that his own guest-friend, the Spartan king Archidamos, might flagrantly avoid it during the first Spartan invasion of Attica in the Peloponnesian War. l6 That the elite may have already decided that it was politic to forego foreign marriages does not mean that the Athenian people found the prospects of formally undermining elite links with the rich and powerful abroad unattractive in 451 B.C. Nevertheless, Perikles' Law is a rather indirect and partial means of cutting the elite off from foreign links, and there must be some doubt as to whether reservations about elite marital behaviour can have been its sole origin. It is possible that marriages to non-Athenian women were coming under material as well as political pressure. Alan Boegehold has recently proposed that Perikles' Law arose from successes in inheritance cases by Athenians who argued that descent from two Athenians was better than descent from one, and should give prior claim to property.17 There was certainly an Athenian law describing the important religious duties of the wife of the archon basileus that insisted that she be Athenian and not foreign ([Demosthenes] 59.75-6). There are also signs that Athenians with foreign mothers could be treated as a distinct group before 451 B.C.: Herodotos (5.94) refers to Peisistratos' son Hegesistratos, born of an Argive woman, as a bastard (nothos), although other sources make the Argive woman Peisistratos' properly married wife; similarly, Plutarch (Themistokles, 1) records that Themistokles was a nothos because he had a foreign mother, and then connects this claim with the existence o f a group of nothoi who exercised at the Kynosarges g y m n a ~ i u m . ' ~ G. Herman, Ritualised Friendship and the Greek City (Cambridge, 1987). Thucydides 2.13.1. This is the earliest case of what comes to be recognized as a standard ploy by enemy generals: see S. Hornblower, A Co~tl~tlentary on Thucydides: Vol. 1, Books I-111 (Oxford, 1991), 251. l7 A. Boegehold, ' "Perikles" Citizenship Law of 45110 B.C.', in A. Boegehold and A. Scafuro (eds.), Athenian Identity and Civic Ideology (Baltimore, 1994). l 8 D. Ogden, Greek Bastardy in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods (Oxford, 1996), 44-58, discusses both these cases. He also argues that the 'impure of descent' of [Aristotle], Constitutzon of the Athenians, 13.5, were the children of foreign mothers and citizen fathers, and that the law on phratries recorded by Philokhoros (Die l5 l6 Iconz. onp. 91 LAW AND T H E REPRESENTATION O F WOMEN I N ATHENS 9 Perikles' Law may well have appealed to popular Athenian prejudice, but this far from demonstrates that it was simply a piece of legal tidiness, a de jure acquiescence to what court decisions had already made de facto. The issue of whether Perikles' Citizenship Law was a recognition of realities or an innovation is an important one. Plutarch (Life of Perikles, 37.3-4) mentions the law in the context of the removal of non-citizens from the citizen register at the time of Psammetikhos' gift of grain to Athens in 44514 B.C. Although this particular connection is highly impla~sible,'~ the suggestion that the law was deliberately designed to limit future access to the material and other advantages of being an Athenian citizen is not without attractions. The Athenian organization of continued Greek resistance to Persian influence i n Asia Minor and the Aegean in the Delian League had brought increasing involvement of Athenians in relatively long-term service abroad. As military activity declined and as Athens exerted ever tighter control over her allies, large numbers of Athenians came to reside abroad in order to administer the cities of what was increasingly an empire, and to maintain Athenian military control by permanently residing in Athenian settlements on allied territory. Athenian men who did not belong to the traditional elite thus acquired new opportunities for forming more or less permanent liaisons with non-Athenian women. Athens was the elite city within the Delian League and her insistence on retaining all of responsibility within the League - for her own members meant that all Athenians were effectively promoted to elite privileges with regard to the allied cities. Perikles' Citizenship Law prevented personal liaisons from acquiring political significance, and prevented families in allied cities from tapping Athenian resources through the citizenchildren of daughters who had married visiting Athenian soldiers or officials.20 n. 18 conc. Fragmente dergriechischen Historiker, 328F35) belongs before 451 B.C. and was designed to protect the rights of aristocratic children of foreign mothers. The former claim seems to me improbable - one would expect more explicit reference to Kleisthenes' foreign mother had this been a factor in his political fortunes following the fall of the tyranny; furthermore, the latter remains far from proven. Even the two cases cited in my text are less than completely compelling, given the dangers of anachronism, whether deliberate or accidental, in authors writing after 450 B.C. l9 Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker, pt 3b (supplement), i, 462-70. 20 From then on, Athenian men abroad for long periods, for example as kleroukhs, could only acquire local wives if they could persuade the Athenians explicitly to allow them the right of intermarriage, something we know to have happened (only) in the 10 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 15.5 There is little doubt that the position of allied cities with regard to Athens was becoming more closely defined in the years around the middle of the fifth century B.C. Our grip on the changing nature of Athenian overlordship is somewhat tenuous, because of the dearth of inscriptional evidence for Athenian relations with her allies prior to the middle of the 450s B.C., but there seems little doubt that c.450 B.C. Athens began to demand that allies perform roles normally expected of Athenian citizens, but without citizen privileges. When the Athenians restored their control to Erythrai after a revolt, probably c.45312 B.C., they insisted that the people of Erythrai bring grain to the festival of the Great Panathenaia." By perhaps 447 B.C. all allies were expected to provide a cow and a panoply for the Great Panathenaia and, probably by the middle of the 440s B.C. certain allies, at least, were having to refer all their capital trials to at hen^.'^ Athenian exclusiveness can be seen also in the development of the doctrine that Athenians had always lived in Attica and were not immigrants. This doctrine of autochthony may have been a specifically fifth-century invention; it was certainly promoted in the second half of the century in a way it had not been previously. The idea was perhaps entirely absent from the work of Aiskhylos, but it is certainly most prominent in tragedy in the works of Euripides written during the Peloponnesian War (particularly Ion and Erekhtheus). A staple of Funeral Orations, at least from the oration which Thucydides puts into the mouth of Perikles in the winter of 43110 B.C. onwards, the doctrine may indeed have been first promoted in those speeches over the war dead.23 Although it acquired a particular force by contrast with the history of the n. 20 coni. case of the Euboians (Lysias 34.3) and of the Lemnians, where the law created a changed situation for Athenians who had been resident on that island since at least 500 B.C. (Isaios 6.13). In neither case are the dates or circumstances of the grant certain: see further Ogden, Greek Bastardy in the Classzcal and Hellerristic Periods, 70-1. '' A Selection of Greek Historical Irrscriptiorrs to the End of the Fzyth Century B.C., ed. R. Meiggs and D. M. Lewis (Oxford, 1969), no. 40. 22 Ibid., nos. 46.41-3, 52.70-6. 23 V. Rosivach, 'Autochthony and the Athenians', Classical Quart., 2nd ser., xxxvii (1987), has stressed the absence of pre-fifth-century evidence for the doctrine. His case is further supported by the way that Kleisthenes made Erekhtheus one of the ten eponymous heroes of his new tribes, something which would hardly have been possible had Erekhtheus enjoyed in the late sixth century the particular role as father of all Athenians which he came to enjoy in the later fifth century. On autochthony, see also N. Loraux, The Children of Athena (Princeton, 1993); N. Loraux, The Invention of Athens (Cambridge, Mass., 1986), 148-50. LAW AND T H E REPRESENTATION O F WOMEN I N ATHENS 11 invading Dorians in the context of the propaganda battles of the Peloponnesian War, it was also a doctrine which distinguished the more ancient Athenians from their Ionian allies in the Delian League, who were held to have set out from Athens to conquer the cities they now inhabited.24Equally important was the theoretical basis which autochthony gave to equality between Athenian citizens. Perikles' Citizenship Law fits well into this context, whereby the Athenians advertised their difference from all other Greeks and expected to demand services from others without giving rewards in return. It ensured that Athenian relations with those in other cities were never more than temporary, and that Athenian relatives were all Athenian. Democracy was in any case hostile to the claims of kinship and was keen to advertise, as again the Funeral Orations did (Thucydides, 2.37.1), that merit was the prerequisite of power and influence. Perikles' Citizenship Law ensured that claims of kinship would not cross the boundaries of the city, but also that no amount of merit on the part of those with whom the Athenians had close political dealings could ever lead to power or influence at Athens. I1 CITIZENSHIP AND T H E REPRESENTATION O F WOMEN If the analysis above is correct, Perikles' Citizenship Law was primarily a symbolic statement. Few Athenians will have had to change their marital intentions, and all Athenians will have had their sense of belonging to an exclusive group reinforced. In what follows, I suggest that this symbolic statement did, however, have an effect on how the Athenians symbolized their own identity, by encouraging public acknowledgement of Athenian wives and mothers. And I suggest that the new symbolic language in turn affected Athenian attitudes. Women had a major place in the symbolization of relations between humanity and the gods in archaic Athens, but virtually no place at all in the symbolic language in which the loss of human life was marked.25 Women are very infrequently represented in Both are mentioned in Thucydides 1.2. The mentality displayed by archaic grave monuments is most thoroughly explored by C. Sourvinou-Inwood, 'Reading' Greek Death to the End of the Classical Period (Oxford, 1995), 140-297. 24 25 12 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 Athenian funerary monuments before c.500 B.C. From the midfifth century onwards, however, the symbolic language in which the dead are commemorated is dominated by women. Women are very frequently represented, both on Athenian funerary monuments and on the white-ground lekythoi (oil flasks) which were deposited in graves. First the crude data.26 Of the 79 funerary reliefs that G. M. A. Richter catalogued, 45 figure men (Plate 1) and 3 figure a man and a woman; none figure just a woman (31 currently figure neither man nor woman).27Similarly, according to the epigraphic data collected by L. H. Jeffery, 54 archaic Athenian grave inscriptions commemorate men, 1 commemorates a man and a woman, 6 commemorate women, and in 8 cases the sex is unclear.28 The relief and free-standing sculptural monuments associated with these inscriptions figure men in 54 cases, women in 8 cases, and, in their current state, neither man nor woman in 20 cases.29 Of figured monuments to the dead, only painted funerary plaques, depicting actual scenes of mourning and parts of the funerary ritual, regularly show women (Plate 2).30 Whatever the reason, women were both rarely commemorated and rarely figured in sculpted commemorations in sixth-century Attica. This situation seems to have been exceptional within the Greek world, since 26 With the argument that follows, cf. K. Stears, 'Dead Women's Society: Constructing Female Gender in Classical Athenian Funerary Sculpture', in N. Spencer (ed.), Time, Tradition and Society in Greek Archaeology: Bridging the 'Great Divide' (London, 1995), esp. 113. 27 G. M. A. Richter, The Archaic Gravestones ofAttica (London, 1961), nos. 35, 37, 59. Strictly speaking, no. 59 shows a woman with a child, where it is the child who is the deceased. This stone comes from Anavyssos, as also did the stele by the same sculptor showing two young men, one deceased, not known to Richter: J. Frel, Death of a Hero (Malibu, 1982). 28 L. H. Teffrev, 'The Inscribed Gravestones of Attica', Annual of the British School at Athens, lvii (1962). 29 I exclude kouroi of uncertain provenance from these figures. Reliefs and freestanding sculptures construe death in rather different ways, but my aim is to show that all the various sculptural representations of death equally eliminate women in archaic Attica. On the difference between reliefs and kouroi, see A. M. D'Onofrio, 'Aspetti e problemi del monument0 funerario attico arcaico', AION, x (1988). 30 J. Boardman, 'Painted Funerary Plaques and Some Remarks on Prothesis', Annual of the British School at Athens, 1 (1955), catalogues 39 plaques or plaque series, in 37 of which it is possible to determine the sex of the figures shown: only women appear in 10, only men in 9, and women and men together in 18. For the relatively unchanging imagery of funerary ritual on vases, see D. C. Kurtz, 'Vases for the Dead, an Attic Selection 750-400 B.C.', in H. A. G. Brijder (ed.), Ancient Greek and Related Pottery (Amsterdam, 1984). 1. Stele of Aristion from Velanideza in Attica, last quarter of sixth century B.C. (Athens National Museum [29]) (Courtesy of Hirmer Fotoarchiv, Munich) 14 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 funerary reliefs of women survive from a number of other archaic cities. 31 Around 500 B.C. Athenians stopped putting monumental markers on graves. The reasons for this are not entirely clear: it is possible that legislation referred to, but not exactly dated, by Cicero (De Legibus, 2.26.64-5) may be relevant; more general resistance to elitist display in the young democracy may also have been a factor. When funerary reliefs reappear in the archaeological record, at a date that is disputed but probably in the third quarter of the fifth century, they look very different (Plate 3). Among the monuments depicting adults in C. W. Clairmont's recent catalogue of classical Athenian tombstones, there are 628 monuments figuring women, 468 figuring men and 1136 figuring both men and women.32Women outnumber men in all the various compositional formations: among reliefs featuring just one figure there are 131 women and 117 men; where reliefs have two adults, there are 241 cases where both are female as against 187 where both are male; where reliefs have three adults, there are 66 cases where all three are women, 29 where all three are men, and so on. Only in the case of reliefs showing children on their own do males outnumber females: where one child appears, that child is male in 80 cases, female in 49.33 What is more, the change B. S. Ridgway, The Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture (Princeton, 1977), 164, 174, 176; also monuments from Crete: J. Boardman, Greek Sculpture: The Archaic Period (London, 1978), figs. 246, 252 (this last is not certainly funerary). Note also D. C. Kurtz and J. Boardman, Greek Burial Customs (London, 1972), 220-2. For a small corpus with a pattern which does seem similar to that at Athens, see P. M. Fraser, Rhodian Funerary Monurnents (Oxford, 1977), 8-9. C. W. Clairmont, Classical Attic Tombstones, 6 vols. (Kilchberg, 1993). I have not counted monuments which are cross-listed by Clairmont. 33 The full statistical breakdown is as follows: stelai with one standing figure: figure male 97, figure female 101; stelai with one seated figure: figure male 15, figure female 30; stelai with single figure kneeling or on horseback: 5 male; stelai with one adult and one child: adult male 74, adult female 96; stelai with two adults: both male 187, both female 241; stelai with one male and one female: 428; stelai with two adults plus child(ren): adults both male 54, adults both female 78, one male one female 120; stelai with three adults: all male 29, two male and one female 157, two female and one male 231, three female 66; stelai with three adults plus child(ren): adults all male 2, two male and one female 31, two female and one male 45, all female 11; stelai with four adults: all male 3, three male one female 21, two male and two female 47, three female and one male 29, all female 2; stelai with four adults plus child(ren): adults all male 0, three male and one female 0, two male and two female 6, three female and one male 9, four female 2; stelai with five adults: all male 0, four male and one female 0, three male and two female 1, three female and two male 4, four female and one male 0, all female 1; stelai with five adults plus child(ren): three male adults and two female 1, four male and one female 1; stelai with six adults: four female and two male 1, three female and three male 1; stelai with six adults plus child(ren): five '* fconz. onp. 16) Scale in inches 2. Fragment of a funerary plaque by Exekias, middle of the sixth century B.C.: dead woman on bief with a woman mourner by her head. (Staatliche Museen, Berlin p18111) (Courtesy of Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin -Preussischer Kulturbesitz) 16 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 in emphasis is apparent from the earliest fifth-century monuments.34 This sculptural evidence can be extended, and perhaps corroborated, by the evidence from the iconography of the whiteground lekythoi. Although lekythoi in other techniques, both black-figure and red-figure, and pots of other shapes were deposited in graves, it is lekythoi with scenes painted on a white ground that seem to have been most closely associated with burial: not only are white-ground lekythoi found only in graves, but also their iconography is dominated by scenes relevant to death and burial. A breakdown, by gender and type of scene, of the images on white-ground lekythoi catalogued by J. D. Beazley broadly charts the chronological change in the iconography of these flasks from about 470 B.C. to the end of the fifth century (Table).35 The earliest white-ground lekythoi, which may not have been exclusively funerary in use, show a more-or-less even distribution between men and women, but women predominate in the work of Beazley's 'Painters of Slight Lekythoi', which includes a large number of figures of Victory and 'white lekythoi'. The Sabouroff Painter, active around 460 B.C., most frequently shows men and women, and has as many lekythoi with just men as with just women. But on the white-ground lekythoi of the Achilles Painter, most of which seem to date to after 450 B.C., women are in the majority (Plate 4). There are also more women on the slightly later lekythoi of the Phiale Painter (Plate 5) and his contemporaries, who are considerably fonder of scenes of women at tombs than the Achilles Painter.36 The latest lekythoi catalogued by ;ri. 33 conr., female adults and one male 1, three female and three male 1; stelai with seven adults: six female and one male 1. "Richter, Archaic Gravestones of Attica, 54 n. 12, lists five reliefs as Periklean: three figure women, and two men. 35 J. D. Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vases, 2nd edn (Oxford, 1963). 'Myth' here includes personifications. All scenes figuring Nikai, Charon, Maenads, Hermes, Sleep and Death, have been classified as 'myth'. Figures of the living and the deceased cannot be systematically distinguished: J. Bazant, 'Entre le croyance et l'experience: le mort sur les lecythes a fond blanc', in L. Kahil, C. Auge and P. Linant de Bellefonds (eds.), Iconographic classique et idelltitis rigionales (BCH Supplement, xiv, Paris, 1986). It is notable that only women and children, and never adult males, are shown with Charon the ferryman who takes the souls of the dead over the Styx: C. SourvinouInwood, 'Images grecques de la mort: representations, imaginaire, histoire', AION, ix (1987). 36 Cf. the similar but differently divided statistics in D. C. Kurtz, 'Mistress and Maid', AION, x (l988), 145. On the Achilles Painter, cf. the remarks of F. Lissarrague, 'La Stele avant la lettre', AION, x (1988), 102: 'These lekythoi, totalling almost 60 ~corir.onp. 1 8 , 3. Stele of Hegeso and a maid, from Athens, c.400 B.C. (Athens National Museum [3624]) (Courtesy of Hirmer Fotoarchiv, Munich) PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 TABLE IMAGES ON WHITE-GROUND LEKYTHOI (C.470-400 B.C.)* Mythic Scenes Non-Mythic Scenes && Beazley Chapters Men Women Both Men Women Both Chs. 21, 36-8 11 14 2 22 25 0 86 1 54 2 21 Ch. 39 12 Ch. 40 4 5 3 73 162 26 9 0 22 28 72 1 Ch. 46 Ch. 50 0 2 1 4 74 33 20 16 6 1 2 Chs. 51, 53, 58, 61 4 62 159 Ch. 64 18 0 2 32 Ch. 74 20 0 6 29 36 200 *Source: J. D. Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vases, 2nd edn (Oxford, 1963), ch. 21, 'Painters of Small Vases'; ch. 36, 'The Villa Builia Painter and his Group'; ch. 37, 'Painters of Nolans and Lekythoi'; ch. 39, 'Painters of Slight Lekythoi and Alabastra'; ch. 40, 'White Lekythoi'; ch. 46, 'The Sabouroff Painter'; ch. 50, 'The Achilles Painter'; ch. 51, 'The Phiale Painter'; ch. 53, 'Other Classic Pot-Painters'; ch. 58, 'Other Classic Pot-Painters'; ch. 61, 'Painters of Lekythoi'; ch. 64, 'Classic Painters of White Lekythoi'; ch. 74, 'Late Fifth-Century Painters of White Lekythoi'. Beazley mainly show men and women (particularly 'youth and woman at a tomb'), but scenes depicting only women still outnumber those of only men. Throughout the history of whiteground lekythoi, mythic scenes never decorated more than a minority of pots; consequently, mythical women make a negligible contribution to women's overall iconographic predominance. These data show that women were acceptable objects of representation on Athenian classical grave monuments and on vases associated with burial in a way that they were not acceptable in Athenian archaic grave monuments. Thus, Athens rejoined other Greek cities that had never adopted the Athenian iconographic limitation of representing only men, even when they had adopted the peculiar form of archaic Athenian reliefs.37 Two questions arise: first, why does Athens differ from other cities in its archaic ~n 36 corrr in number, have an iconography that is essentially feminine - musical scenes, domestic scenes, scenes of preparation for visits to the tomb. Scenes showing the funerary stele are much rarer, just 18 examples, and in 15 of those at least one woman is shown at the tomb, carrying offerings'. 37 Note B. S. Ridgway, The Severe Style in Greek Sculpture (Princeton, 1970), 45-8, 51: 'funerary stelai stop in Attica but spread elsewhere in the Attic format. Yet the content, with its intimacy and its representations from real life, seems m direct continuation of Ionic tradition, or at least alien to earlier Attic gravestones' (51). 4. Woman and departing warrior: white-ground lekythos found at Eretria and attributed to the Achilles Painter, c.440 B.C. (Athens National Museum [1818]) (Courtesy of Himer Fotoarchiv, Munich) 20 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 practices? and secondly, why does Athens change her own practices between the archaic and classical periods? Classical Athens was more repressive in its dealings with women than other Greek cities, particularly in matters of property rights: Athenian women could not acquire property contractually or deal with it, and are not found among Athenian landowners, moneylenders or slave owners.38 These limitations on women's rights were already in place in the sixth century B.C., and in explaining women's different place in archaic Athenian funerary monuments this difference in legal status would make a promising place to start. But since the legal position of women in Athens did not change significantly between the sixth and the fourth centuries, I shall concentrate in this article on the question of why women's place changed in Athenian funerary monuments. Whatever the reasons for Athens keeping women peculiarly tightly restricted in the archaic period, I suggest that it is the classical decision to bring women into the fore in funerary imagery, while not at all relaxing the restrictions on women's rights, which most urgently demands explanation. We might posit three possible changes in Athens: changes in attitudes to women, attitudes to death, or in artistic habits. Only those who subscribe to the view that art has its own momentum which is independent of society at large will be attracted by the last possibility. It has been suggested that it was the surplus of sculptural skill released by the completion of the Parthenon project which brought about the reinvention of the sculpted grave relief at Athens, but such an explanation cannot explain the iconography adopted in those stelai: males predominate in the Parthenon frieze, which is stylistically closest to the early ~ t e l a i . ~ ~ Can some change in attitudes to death explain the new prominence of women? Archaic reliefs tend to focus on the life lived: the hoplite (Plate 1) or the athlete is paraded before our eyes. Archaic free-standing sculptural monuments for dead men take the form of kouroi: naked male figures with feet flat on the ground, one leg advanced, hands by their sides and face staring directly ahead. Here the sculpture gives no sense of the 38 See the succinct statement by G. E. M. de Ste Croix, 'Some Observations on the Property Rights of Athenian Women', Classical Rev., 2nd ser., xx (1970); D. M. Schaps, Economic Rights of Women zn Ancient Greece (Edinburgh, 1979), esp. ch. 7. Schaps stresses the gap between law and practice in the classical evidence. 39 For that explanation, see C. M. Robertson, A History of Greek Art (Cambridge, 1975), 365. 5. Dead woman shown beside her own tomb which is being visited by another woman. White-ground lekythos found at Oropos and attributed to the Phiale Painter, c.440-30 B.C. (Museum Antiker Kleinkunst, Munich) (Courtesy of Hirmer Fotoarchiv, Munich) 22 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 individual's achievements, but the invitation to the viewer to 'stand and weep', which is found on some of the inscriptions accompanying funerary kouroi, is not inappropriate: the male viewer finds his gaze mirrored by a figure with whom he shares everything except his death.40 Virtually no classical monuments figure a 'context-free' individual in the way the archaic kouroi do, and only a few classical grave reliefs, such as those which show cavalrymen in action, focus on the achievements of the life lived. The vast majority invoke the social setting of the deceased by showing a man talking with his contemporaries or in a domestic setting, or a woman with her family or another female in attendance (Plate 6). By putting the figure of the deceased into a setting in which relationships rather than actions are most prominent, the classical reliefs do not so much commemorate the achievements of a life as register the scale and nature of the loss to others, and to the family circle. These are scenes which are easily universalized and they speak the language of virtue which is a public language, as associated funerary epigrams make clear.41 If we are seeking an explanation of the change in iconographical emphasis in terms of changing attitudes to death, then it would seem to entail a shift from seeing death as ending the more-or-less public achievements of an individual, to seeing death as disrupting the face-to-face society of family and friends.42 We might want to go further than this. The emphasis which J. Reilly has laid on the connections between the iconography of 'mistress and maid' scenes on white-ground lekythoi and the iconography of marriage also has implications for the 'mistress and maid' iconography which is common in grave stelai (Plate 3).43These scenes do not simply evoke the household from 40 I depart here from the views expressed by Sourvinou-Inwood, 'Reading' Greek Death, 252-4, for whom the nakedness of kouroi is the nakedness of the athlete. That thesis seems to me difficult to sustain considering that athleticism is marked in reliefs by the addition of an attribute, particularly an aryballos (266). 4 1 See G. Hoffmann, 'La Jeune Fille et la mort: quelques steles a epigramme', AION, x (1988). 42 Cf. R. G. Osborne, 'Death Revisited, Death Revised: The Death of the Artist in Archaic and Classical Greece', A r t Hist., xi (1988), and Sourvinou-Inwood, 'Reading' Greek Death, 247, on the way fifth-century scenes conflate Charon (the boatman who conveys souls across the Styx) and a visit to the tomb to represent 'death seen as both a personal experience and a family affair'. 43 J. Reilly, 'Many Brides: "Mistress and Maid" on Athenian Lekythoi', Hesperia, lviii (1989). See also I. Jenkins, 'Is There Life after Marriage? A Study of the Abduction Motif in Vase Paintings of the Athenian Wedding Ceremony', Bull. Instit. Classical Studies, xxx (1983); Kurtz, 'Mistress and Maid'; R.-M. Moesch, 'Le Mariage et la mort sur les loutrophores', AION, x (1988). 6. Marble grave marker in shape of a lekythos, from Salamis, c.375 B.C. (Glyptothek, Munich [498]) (Courtesy of Hirmer Fotoarchiv, Munich) 24 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 which the deceased woman has gone. They invite comparison between the departure from the marital household in death and departure from the natal household in marriage and, in doing so, they also evoke the sense of promise cut short by portraying the woman at her most promising. What archaic grave monuments there were to women seem to have taken the form of korai, the female equivalent of the kouroi, and to have made the link between marriage and death. Korai were standing figures of young women, variously and often elaborately clothed, usually with some object or offering in one hand, staring straight ahead. They were much used as dedications in sanctuaries, where it is attractive to see not only the offering held, but also the nubile woman herself, as symbolizing the exchange between men and the gods.44 The two korai known to have been used as grave markers in Attica both explicitly connect death and marriage. In the case of the kore now in Berlin (Plate 7 ) ) the link is made by the pomegranate that the figure holds in her right hand. The pomegranate was a symbol of fertility, but it also had mythological associations with death: it was eating a pomegranate while abducted to Hades that prevented Persephone, daughter of the goddess Demeter and also known as Kore, from returning permanently to life above earth.45 In the case of the kore monument for Phrasikleia, the link is made by the epigram which declares that she 'will always remain a kore having obtained that name from the gods instead of marriage'.46 In as far as classical stelai exploit the analogy between marriage and death, they only take up something which had been available also in archaic monuments. That finding is further supported by literary evidence. There too the link between death and marriage is prominent, but although we know it most clearly from tragedies written in the second half of the fifth century B.C., it is apparent that it was already present in plays R. G. Osborne, 'Does the Sculpted Girl Speak to Women Too?', in I. Morris (ed.), Classical Greece: Ancient History and Modern Archaeology (Cambridge, 1994), 92-5; cf. Sourvinou-Inwood, 'Reading' Greek Death, 244-6. 45 In the iconography of the classical lekythoi and reliefs it is curious that no use is made of the parallel with Persephone, just as no allusion is made to either Dionysiac or other mystery cults which were interested in the afterlife: S. G. Cole, 'Voices from beyond the Grave: Dionysus and the Dead', in T. H. Carpenter and C. A. Faraone (ed.), Masks of Dionysus (Ithaca, 1993). I~zscriptionesGraecae, i3, 1261. 1 7. Kore from Keratea, c.550 B.C. (Staatliche Museen, Berlii [1800]) of Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin -Preussischer Kulturbesitz) 26 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 early in the century.47 The story of Alkestis, who agrees to submit to an early death herself in order that her husband should be exempt from death altogether, was put on stage by Phrynikhos in the first quarter of the fifth century; it figures similarly in the extant play by Euripides, which dates from the third quarter of the century. If changing ways of thinking about death lie behind the new prominence of women on grave monuments, it can only be a case of new emphasis, not of the adoption of some view of death that had been unheard of in the sixth century. If we turn to attitudes to women, what change in attitudes to women would adequately explain the new iconography? There was no general reluctance to put women on display in works of art in archaic Athens. The Athenian Acropolis displayed numerous dedications in the form of korai, and women also appeared in Athenian votive reliefs. It would seem, therefore, not to be women that the society was loathe to display, but the death of women, which it rarely regarded as worthy of prominent commemoration. Should the move from commemoration of individual achievements to the marking of loss and the disruption of the family be seen as consequent upon a change in attitude towards women? Where individual achievements in the public eye are seen as most important, in a society where public life is the preserve of men, men rather than women are bound to be the focus of attention. Where the family group is important, both women and men are likely to be commemorated. Women might appear in dedicatory sculpture because their exchange in marriage conveniently figures the exchange with the gods. They would be absent from archaic funerary monuments, however, because individually they played no role which it was important for the society as a whole to commemorate. They would appear in classical grave sculpture because the qualification for commemoration was no longer individual achievement for the society at large, but the role played within the family and immediate social group. I have explored two possible types of explanation for the changing prominence of women in sculpted grave monuments at Athens: first, that it became much more common for death to be thought of as a force disrupting the family group, perhaps like a 47 R. Seaford, 'The Tragic Wedding', J l Heller~ic Studies, cvii (1987); R. Rehm, Marriage ro Death: The Conflation of Wedding and Funeral Rituals in Greek Tragedy (Princeton, 1994). The unity of wedding and funeral in Euripides' Alkesris is brought out most clearly at lines 918-22. LAW AND THE REPRESENTATION O F WOMEN IN ATHENS 27 second marriage, rather than simply as something ending the achievements of an individual life; and secondly, that what was seen as important about individuals came to be less what they achieved personally on the city stage, and more what they contributed to the constituent elements of the city, the households. As a result, therefore, women came to be more highly valued and so more readily commemorated. Is it possible to demonstrate the plausibility, or otherwise, of either explanation? Funerary display was a political matter. Concern for the impact of elaborate funerals is reflected in Solon's legislation to curb funerary display, and the subsequent law referred to by Cicero attests a concern about funerary r n o n ~ m e n t s .Whether ~~ as a direct result of the law or not, sculpted funerary monuments disappear from the archaeological record around the end of the sixth century B.C. When they reappear in the second half of the fifth century B.C., we must suppose that, whether or not the law had been repealed, public concern had lessened. Did fifth-century funerary reliefs differ from sixth-century monuments in ways that would make them less politically offensive to the city? The problem with sixth-century funerary monuments cannot have been an objection to marking past lives as such. Increased deposition of painted pottery in tombs actually makes graves more visible archaeologically just at the moment that sculpted monuments disappear.49 Moreover, at least from the 460s B.C. onwards, the city itself erected monuments to those who died in war. The objection must have been to the sort of monuments put up in the sixth century. Sixth-century monuments primarily commemorate the deaths of young rneny5Oand they most commonly commemorate them by evoking the world of the gymnasium. The disappearance of archaic sculpted monuments coincides with the arrival of democracy, and it is not difficult to see that the young democracy might view these commemorations of the lifestyle of wealthy young men as potentially divisive, points around which family groups might be rallied with politically subversive intent. Objecting to individual display and encouraging all b S P l ~ t a r ~ Life h , of Solon, 21.5; Cicero, De Legibus, 2.26.63-5. See further R. Seaford, Reciprocity and Ritual: Homer and Tragedy in the Developing City-State (Oxford, 1994), 74-86. j9 I. Morris, Burial andAncient Society: The Rise o f t h e Greek City-Stare (Cambridge, 1987), 73, fig. 22; I. Morris, 'Everyman's Grave', in Boegehold and Scafuro (eds.), Athenian Identitj~and Civic Ideology. On this point, see esp. Sourvinou-Inwood, 'Reading' Greek Death, 285-94. 28 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 Athenians to ape those aspects of elite burial which they could afford to copy seem perfectly consistent. If classical grave reliefs promoted a vision of death which stressed not the lifestyle of the jeunesse dore'e but the disruption caused to the family by the loss of an individual member, then that vision might well be seen as less hostile to democracy. It might indeed be seen to promote democracy, since such losses were paralleled in all households, poor as well as rich. If funerary display was political, so too, as we have seen, was marriage. The end of the archaic sculpted funerary monument more or less coincides with the end of high profile marriages between the Athenian elite and the elites of other Greek cities. J.-P. Vernant noted: 'In the Athens of the period after Cleisthenes, matrimonial unions no longer have as their object the establishment of relationships of power or of mutual service between great autonomous families; rather, their purpose is to perpetuate the households, that is to say the domestic hearths that constitute the city, in other words to ensure, through strict rules governing marriage, the permanence of the city itself through constant r e p r o d u c t i ~ n ' .Because ~~ family links and family claims to fame had traditionally been a basis for asserting political power, the democratic city had an interest in the nature of matrimonial unions, just as it had an interest in the nature of funerary display. Because claims to belong to the city, like claims to belong to a particular family, depended on descent and hence on marriage, politically acceptable marriage and politically acceptable domestic relations needed to be promoted. But if the elite began to change their marriage patterns soon after the inception of democracy, it is only after 450 B.C., rather than after 507 B.C., that emphasis on women and the household becomes apparent in the archaeological record. As we have seen, women dominate the iconography of white-ground lekythoi from about 460 B.C., and they dominate classical grave stelai from their reappearance sometime in the third quarter of the fifth century. That women in a domestic context should appear for the first time in Athenian grave monuments in the second half of the fifth century simply as a trickle-down effect from legislation in the last decade of the sixth century seems highly improbable. We need a further trigger some time in the middle of the fifth century. 51 Vernant, 'Marriage', 50. LAW AND T H E REPRESENTATION O F WOMEN I N ATHENS 29 The changed pattern of elite marriage became embodied in legislation with Perikles' Citizenship Law of 451 B.C. If Kleisthenic democracy asserted the reproductive function of marriage at the expense of marriage as a way of enhancing status or forging diplomatic links (among other things), the law made it important to identify exactly who the marriage was to and who the mother of the legitimate children was. It was no longer just politic to avoid having a foreign wife: advertising the identity, citizen status and marriage of parents became vital to maintaining one's own status. But how could a claim to citizen status be advertised in a democratic city? To publicize one's father in death as in life was, in a patrilineal society, to promote the family line. Democratic Athens took its opposition to claims based on lineage so far as to suppress patronymics on public monuments to the war dead. Advertising the particular identity of the father is something which the Aristotelian tradition holds Kleisthenes himself to have been worried in any case, once both parents had to be citizens, advertising one's father's identity was no longer sufficient. By insisting that the household conform to a specific model, Perikles' Law effectively sanctioned the display of conformity. The classic grave stele provided a means for that display that had unique advantages. To promote one's wife and the mother of one's children appropriately drew attention to the household as an ephemeral unit rather than as a long lineage. But in a society where women of status were not displayed to unrelated men except in the controlled circumstances of religious festivals, opportunities to draw public attention to wives and mothers were few. The death of a wife or mother became the prime moment for advertising her identity and anchoring claims-to citizenship: death and marriage acquired a political as well as a structural c o n n e c t i ~ n .Grave ~~ reliefs, which were private monuments 5 2 Cf. [Aristotle], Constitution of theilthenians, 21.4, with T. F. Winters, 'Kleisthenes and Athenian Nomenclature', Jl Hellenic Studies, ciii (1993), 162-5. 53 Many funerary monuments figuring women, including some early ones, are to metics, who would not have had the same political interests; however, the pressures on the metic community to conform to local practice, and indeed the expectations of sculptural workshops, will have ensured that metic monuments were shaped iathe image of citizen monuments. That classical Athenian monuments share many iconographical features with those of the cities from which metics came will have made conforming further to Athenian citizen practice unproblematic. Metic monuments do not emphasize metic status; rather than employing official nomenclature, which referred to the deme of residence of the metic, the reliefs identify metics by their ethnics. 30 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 displayed to the public at large, often in family enclosures within the cemetery, provided the opportunity to display a female relative's identity without breaching those protocols which otherwise surrounded the naming of women.54 The date at which women become dominant on white-ground lekythoi supports the view that Perikles' Citizenship Law only instantiated the logic implicit in earlier democratic arrangements; however, the date at which sculpted grave reliefs reappear suggests that it might nevertheless have played a major part in bringing about a distinctly female dominance of figurative memorials to the dead. Did it also effect a revolution in the lives of women themselves? The contrast between the experience of visiting a sixth-century B.C. Athenian cemetery, dominated by images of athletic young men and the occasional older warrior (Plate I), and the experience of visiting a late fifth-century B.C. cemetery, dominated by domestic scenes and by women (Plate 3), is marked. The depredations made on Athenian cemeteries in the interests of the rapid building of fortifications after the Persian Wars meant that no Athenian would have had this 'before-and-after' experience, but the sculpted and painted funerary images cannot but have impressed their ideals upon those who regularly observed them none the less. Funerary monuments ascribed status and value, and established expectations. In the late fifth century B.C. those expectations firmly embedded the woman in the household and offered her only a heavily gender-stereotyped role. But because the same reliefs so often displayed men with women, and also displayed men in a domestic context, they laid down markers of the partnership between men and women in the home and their joint role in defending and perpetuating the city. We should contemplate the possibility that the changing appearance of the cemetery may have begun by changing the representations of women, but that it became a means of changing attitudes towards women. Can the change from living in a society where images of women were never present in cemeteries to living in one where women were predominant have failed to raise issues which went well beyond the legal question of whether a woman was born to Athenian 54 The protocols changed on the death of a woman, but were not abolished: D. Schaps, 'The Woman Least Mentioned: Etiquette and K'omen's Names', Classical Quart., 2nd ser., xxvii (1977). LAW AND THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN ATHENS 31 parents, and hence a possible wife for a man born of Athenian parents? If classical grave reliefs mark, in part, a politically occasioned change in emphasis in attitudes to women, this should be visible in other aspects of Athenian self-expression. It is unfortunate that among all the rich remains of fifth-century Athenian literature only the tragedies of Aiskhylos date to before the middle of the century. The literary factors shaping the works of the tragedians are complex, and comparisons between the work of Aiskhylos before, and the work of Sophocles and Euripides after, Perikles' Citizenship Law are thus perilous in the extreme. Certain observations can be offered, nevertheless. Running through the whole of fifth-century tragedy is a 'disruptive interplay of civic and familial discourses in which the specific roles of women play an essential part'.55 Powerful female figures are to be found in Aiskhylos as much as in later writers, and issues of marriage dominate Aiskhylos' Persians and Suppliant Wornen, as they later dominate Euripides' Medea and Hippolytos. Women's involvement in ritual, though not a major concern in Aiskhylos extant plays, is well-attested in surviving fragments of early tragedy, as well as in Euripides' Bacchae. It is as true of the plays of Sophokles as it is of Aiskhylos' Oresteia that the household is shown to be essentially linked to, and understood in relation to, the wider society of the city.56Against these continuities, however, we might ask whether it is by chance that it is Aiskhylos' Oresteia that has become the classic text for discussions of patriarchy, outside the study of classics as well as within it.57 Is it simply coincidence that the classic comparison between the man standing in the line of battle and the woman bearing the pain of childbirth, which brings out the way in which the woman too fights for the city by producing the citizens of the future, comes in Euripides (Medea, 250-1)?58 Part of the 'deglamorization' of myth59 in Euripides involves building up illusions of reality in which mythical women are presented in domestic contexts: mark the contrast between the homely setting which Euripides provides for his Elektra, and the setting of Elektra in S. D. Goldhill, Readtng Greek Tragedy (Cambridge, 1986), 115. Ibzd., 152-3. 57 Ibzd., 51-6. N. Loraux, The Experzence of Tezrestas: The Femzntne and the Greek M a n (Princeton, 1995), 23-44. 5 9 W. G. Arnott, 'Double the Vision: A Reading of Euripides' Electra', Greece and Rome, xxviii (1981), 181. 55 56 32 PAST AND PRESENT NUMBER 155 Aiskhylos Choephoroi, a play with which Euripides directly invites comparison. The public presentation of illusions of domestic reality on stage directly parallels the display of the household at home in the grave reliefs. The possibility should at least be entertained that the greater prominence of domesticity, and the greater importance of the Athenian wife, may have encouraged such changing tragic images. CONCLUSION In 45110 B.C. an Athenian mother was added to the official requirements for Athenian citizenship. This requirement may well have been presented as a democratic move, clipping the romantic politics of the elite, though these were in fact largely a thing of the past; it may well also have appealed to popular prejudice against men with non-Athenian mothers and have coincided with arguments in the law-courts that men with two Athenian parents should have priority in inheritance. The law certainly fitted in with other moves by the Athenians to establish their exclusiveness and superiority over other Greeks, and particularly over their allies in the Delian League. The very variety of possible reasons for voting for Perikles' Citizenship Law may itself have been a factor in seeing it passed. Whatever factors contributed to the conception and passage of the law, I have tried to show that the effects of the legislation extended well beyond what anyone involved was likely to have foreseen. Formal exclusion of non-Athenian mothers from Athenian political society led to an emphasis on Athenian wives and mothers, and brought women literally into the public eye: men secured their own claims to citizen status by advertising that their wives and mothers conformed to the ideals of Athenian womanhood, and that their homes were models of domestic regularity, unsullied by the exotic. Such advertisement reinforced the stereotype of the Athenian woman but it also promoted the domestic setting as the chief source of citizen status and made it acceptable to put the man, so frequently previously figured in the gymnasium or on the field of battle, back into that setting. By doing so the agenda of masculinity was alteredY6O the household b0 I explore the changing agenda of masculinity further in 'Sculpted Men of Athens: Masculinity and Power in the Field of Vision', in L. Foxhall and J. Salmon (ed.), Thinking Men: Masculinity and its Sey-Representation in the Classical Tradition (London, 1997). LAW AND THE REPRESENTATION O F WOMEN IN ATHENS 33 acquired a new and different place in Athenian ideology and, if women's work itself remained essentially unaltered, it had at least ceased to be unseen and unsung. Corpus Christi College, Oxford Robin Osborne http://www.jstor.org LINKED CITATIONS - Page 1 of 2 - You have printed the following article: Law, the Democratic Citizen and the Representation of Women in Classical Athens Robin Osborne Past and Present, No. 155. (May, 1997), pp. 3-33. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-2746%28199705%290%3A155%3C3%3ALTDCAT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H This article references the following linked citations. If you are trying to access articles from an off-campus location, you may be required to first logon via your library web site to access JSTOR. Please visit your library's website or contact a librarian to learn about options for remote access to JSTOR. [Footnotes] 7 Do Bureaucratic Politics Matter?: Some Disconfirming Findings from the Case of the U.S. Navy Edward Rhodes World Politics, Vol. 47, No. 1. (Oct., 1994), pp. 1-41. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0043-8871%28199410%2947%3A1%3C1%3ADBPMSD%3E2.0.CO%3B2-K 23 Autochthony and the Athenians Vincent J. Rosivach The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 2. (1987), pp. 294-306. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0009-8388%281987%292%3A37%3A2%3C294%3AAATA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-R 38 Some Observations on the Property Rights of Athenian Women G. E. M. de Ste. Croix The Classical Review, New Ser., Vol. 20, No. 3. (Dec., 1970), pp. 273-278. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0009-840X%28197012%292%3A20%3A3%3C273%3ASOOTPR%3E2.0.CO%3B2-N 43 Many Brides: "Mistress and Maid" on Athenian Lekythoi Joan Reilly Hesperia, Vol. 58, No. 4. (Oct. - Dec., 1989), pp. 411-444. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0018-098X%28198910%2F12%2958%3A4%3C411%3AMB%22AMO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Q NOTE: The reference numbering from the original has been maintained in this citation list. http://www.jstor.org LINKED CITATIONS - Page 2 of 2 - 54 The Woman Least Mentioned: Etiquette and Women's Names David Schaps The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 27, No. 2. (1977), pp. 323-330. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0009-8388%281977%292%3A27%3A2%3C323%3ATWLMEA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-6 NOTE: The reference numbering from the original has been maintained in this citation list.