puad 662 – national budgeting - School of Policy, Government, and

advertisement

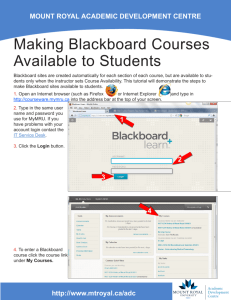

PUAD 662 – NATIONAL BUDGETING, SPRING 2016 Joseph J. Minarik jminarik@gmu.edu 202-469-7816 – office 703-435-0936 – home 703-509-3244 – cell Please e-mail to arrange appointments. 1. Course Description This course will focus on how the national government raises revenue and spends it. That sounds simple enough, just like your family budget – except unlike your family budget, the participants don’t love each other. In fact, there are thousands of participants, each with differing interests and preferences for the use of scarce resources. How much of the economy to devote to government through taxes, and how to allocate those revenues, are the most important decisions that political leaders at all levels of government must make in every year. They can decide to avoid some tough choices – reforming immigration and social security are two recent major policy choices that leaders ducked for fear of the political consequences. But unlike some other issues, decision-makers must choose the size and distribution of the pie every year, whether they like it or not, by commission or omission. Budgetary choices carry large economic and political stakes. From an economic perspective, the federal budget bottom line constitutes the nation’s fiscal policy – the primary tool for federal elected officials to manage the economy and deliver on campaign promises to create full employment with low inflation. The budget’s bottom line – the size of the deficit or surplus both now and in the future – has important consequences for the growth of the economy and for the distribution of economic resources among various interests. Individual budgetary decisions also have important economic implications. The decision to invest public resources in a particular area can have profound effects on private investments. For example, the decision to provide federally subsidized flood insurance has set in motion the settlement of beaches and other low-lying flood plains throughout the country, because home owners, realtors and developers are indemnified from risk by federal insurance payouts. While economically important, the budget is at its heart a political document. However officials try to hide it, the budget reveals their underlying priorities about two important values – how much government should extract from the economy, and which claimants deserve more or less of the scarce resources that are raised. To raise the stakes even more, not only are resources for public programs limited, but claims of need are virtually infinite. Generals testify about the woeful state of military armaments and readiness with the same earnestness and drama with which highway engineers attest to the many bridges about to collapse – and both can cite figures denominated in trillions of dollars for the investments needed to mitigate the risks to the public and the republic. Making tradeoffs among competing claims for limited resources is an inherently political process. No one has figured out a magic analytic formula – on which everyone would have to agree – to determine the relative merit of these competing claims. Elected policymakers sometimes obfuscate about the overall bottom line to appear to provide sufficient resources for each of the many interests that petition for budgetary largesse, but such claims inevitably collide with the unavoidable resource constraint. Thus, budgeting is at its heart a political process. But it is also a technical and managerial process. Making the choices requires seemingly mind numbing processes to weigh competing claims and ensure that all the numbers add up. The technical jargon and cost accounting involved with budgeting at times seems to mask the underlying political stakes involved. But the manipulation of budget concepts, accounting and processes is as infected with politics as the actual choices that are made with those tools. Savvy interest groups have their own litanies of budget process reforms which, while always argued as saving the republic from imminent harm, have the fortunate side effect of just happening to benefit their own interests. Thus, for example, it is no surprise that highway lobby organizations advocate a capital budget – a budget structure designed to highlight and presumably more fully fund the vast inventory of perceived unmet needs in this area. Budget processes are not just about how we make choices, but also about how we track and implement those choices. Legislators and Presidents alike are held accountable not just for the choices they make but for the results (both macroeconomic and microeconomic) of the programs and operations they fund. The execution phase of budgeting is important because it determines how agencies, the President and the Congress ensure that actual spending is effective, efficient and, above all else, legal. This course will help you better understand how budget systems address these political, economic and managerial issues. We will work together to explore the following major areas: --The conceptual basis for the government’s role in the economy and the society --The economic rationale for and implications of national budgeting decisions --The political processes shaping budgetary choices --The role played by various institutions in federal budgeting --The design and implementation of the budget formulation and execution process at the federal level --Potential reforms that are proposed for changing the budgetary process 2. Course Expectations Students will be expected to gain a conceptual understanding of the budget process in general as well as a familiarity with key features of budget formulation and execution. Students will deal with these issues through a combination of readings, class discussion, group projects and exams. A series of short (two-page) essays will be required periodically to test students’ mastery of readings and concepts. Midterm and final take-home exams will be administered. Students will be responsible for participating in discussion of course readings each week. In addition, students will form teams in class to complete a report on key budget policy issues. Teams will be responsible for presenting case studies to illustrate budget trends: the implications of health care; social security; infrastructure investment; and other components of the budget. Grading will follow these weights: Final exam – 35% Midterm – 25% Two-pager memos – 20% Class presentation and general oral participation – 20% 2 One basic text book is assigned: Allen Schick, Federal Budget: Policy, Politics and Process, 3rd edition (Washington, D.C.: Brookings, 2007) Considerable reliance will be placed on budget documents and reports issued by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, the Congressional Budget Office and the U.S. Government Accountability Office which can be accessed on line at those agencies’ web sites (omb.gov; cbo.gov; gao.gov). Three particularly useful documents are --The GAO’s budget glossary that provides a handy definition of budgetary terms with which you may not be familiar. (U.S. Government Accountability Office, A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process (GAO-05-734SP) www.gao.gov) --The CBO’s annual Budget and Economic Outlook (January 19, 2016) (www.cbo.gov) --The OMB’s FY2017 Budget documents, particularly the Analytical Perspectives and the Historical Tables (expected soon) (www.whitehouse.gov/omb) In addition, various handouts will be provided through the University’s Blackboard. You will be given instructions to access these materials. Students should notify the instructor if they are unable to attend a particular class by email either before or immediately after class. Unexplained absences will be duly noted in determining the student’s grade. Students will be required to complete all assignments on time. Should students be late, the grade will be lowered by one half of a grade in deference to those students who submitted work on time. Plagiarism: Students must adhere to the honor code of George Mason University, including the university’s policy on plagiarism. Using the words or ideas of anyone other than yourself, and pretending those words are your own, constitutes serious academic dishonesty and will not be tolerated. Any words or ideas presented in your paper which are not your own must be properly quoted and/or cited. To guard against plagiarism and to treat students equitably, written work may be checked against existing published materials or digital databases available through various plagiarism-detection services. Accordingly, electronic forms of submitted materials may be requested. The Honor Code policy endorsed by the members of the Department of Public and International Affairs for the types of academic work indicated below is set out in the appropriate paragraphs: 1. Quizzes, tests and examinations: No help may be given or received by students when taking quizzes, tests, or examinations, whatever the type or wherever taken, unless the instructor specifically permits deviation from this standard. 2. Course Requirements: All work submitted to fulfill course requirements is to be solely the product of the individual(s) whose name(s) appears on it. Except with permission of the instructor, no recourse is to be had to projects, papers, lab reports or any other written work previously prepared by another student, and except with permission of the instructor no paper or work of any type 3 submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of another course may be used a second time to satisfy a requirement of any course in the Department of Public and International Affairs. No assistance is to be obtained from commercial organizations which sell or lease research help or written papers. With respect to all written work as appropriate, proper footnotes and attribution are required. 3. CLASS READINGS AND ASSIGNMENTS Lecture 1, January 25, and Lecture 2, February 1 – What is a budget, anyway? Basic concepts; structure; the state of the budget ASSIGNMENT DUE ON THE FIRST DAY OF CLASS (OR IMMEDIATELY THEREAFTER): Submit before the first class a brief memo (maximum two pages – this memo will not be graded – submit to the instructor by e-mail) answering two questions: (1) Why did you enroll in this class? (“It is required for my job” or “For career advancement” are perfectly acceptable answers, but please elaborate so that the instructor will know better how to meet your needs.) (2) Why do you consider this subject matter important, and / or what do you consider intellectually interesting about it? (The answer to this question may of course in effect be the answer to question (1).) Also, if you have a personal CV or resume readily available, please provide it to help me to understand the background of the class. This session will discuss the overview of the course: the criteria for shaping the government’s role in the national economy and society. Public finance and public choice literatures will be discussed as well as historical data comparing U.S. experience with other OECD nations. We will discuss the differences between budgeting for federal government, states, private firms and the family. (“Why can’t the federal government be run like a business?”) We will take a close look at the current status of the federal budget as a motivation for the course. High-Priority Reading: Joseph J. Minarik, “What Is the Structure of the Budget?” prepared for the National Press Foundation – on Blackboard Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook PBS Frontline http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tentrillion/view/ Office of Management and Budget, “Stewardship,” in Analytical Perspectives, Fiscal Year 2001 Budget http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BUDGET-2001-PER/pdf/BUDGET-2001-PER-4-2.pdf, box beginning on pdf page 2 (printed page number 18) Bipartisan Policy Center, Restoring America’s Future, “Executive Summary,” “Summary of Recommendations” http://bipartisanpolicy.org/sites/default/files/BPC%20FINAL%20REPORT%20FOR%20PRINTER%2 002%2028%2011.pdf ASSIGNMENT due on the date of Lecture 3: Before the class, each student will play a “budget game” to familiarize ourselves with federal budget choices. http://crfb.org/stabilizethedebt/ Imagine that you work for a Member of Congress. Write a two-page memo for your boss (submitted to the instructor by e-mail), discussing the lessons you have learned about what it will take to close the fiscal gap discussed in the movie that is assigned above, informed by playing the budget game. 4 Lecture 3, February 8 – Macrobudgeting: The Economic Effects of the Federal Budget Continuing from the previous classes, discussion will place the economic role of the federal budget in perspective, including a primer on macroeconomics and the role of fiscal policy in influencing macroeconomic performance. Recent historical experiences and models of long-term economic outcomes will also be discussed. High-Priority Reading: Van Doorn Ooms et. al., The Federal Budget and Economic Management – Blackboard Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook GAO, Federal Debt: Frequently Asked Questions http://www.gao.gov/special.pubs/longterm/debt/index.html Alan Blinder on “Job-Killing Spending” http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303635604576392023187860688.html John Hayward, “How Government Spending Kills Jobs” http://www.humanevents.com/2011/06/21/how-government-spending-kills-jobs/ Suggested Reading: Alan Auerbach, “American Fiscal Policy in the Post-War Era: An Interpretative History” – Blackboard Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Fiscal Year 2017, “Interactions Between the Economy and the Budget” Benjamin Friedman, “Deficits and Debt in the Short and Long Run” http://www.nber.org/papers/w11630.pdf?new_window=1 Carlo Cottarelli, et.al., “Default in Today’s Advanced Economies: Unnecessary, Undesirable and Unlikely” (Washington, D.C.: IMF, 2010) http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/spn/2010/spn1012.pdf ASSIGNMENT due on date of Lecture 4: Deficits exploded seven years ago to the highest levels ever recorded in peacetime; but some argue now that the deficit is declining and the urgency of the problem is reduced, if not eliminated. Assume you work for a Member of Congress, and write a memo discussing whether the current deficit is “too high,” “two low” or “just right” for now. In your answer identify the economic risks entailed in running high deficits now and the risks involved with cutting deficits to bring about a balanced budget over the near term. How should your boss balance these risks? Lecture 4, February 15 - Assessing Long-Term Commitments and Fiscal Risks Session will explore how to think about long-term commitments in the federal budget. Longterm budget models will be examined to ascertain the nature of the long-term exposures in the federal budget. New approaches for measuring and presenting those commitments in federal budgeting will be assessed. Potential linkages between federal budgeting and accounting will be examined to test whether additional value could be realized from the integration of these two financial disciplines. 5 High-Priority Reading: Bipartisan Policy Center, Restoring America’s Future http://bipartisanpolicy.org/sites/default/files/BPC%20FINAL%20REPORT%20FOR%20PRINTER%2 002%2028%2011.pdf (sections on health care and Social Security) Congressional Budget Office, The 2015 Long-Term Budget Outlook, June 16, 2015 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/50250 The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, Moment of Truth, December, 2010 http://www.fiscalcommission.gov/sites/fiscalcommission.gov/files/documents/TheMomentofTruth 12_1_2010.pdf Henry J. Aaron, “How to think about the U.S. Budget Challenge,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (2010) http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2010/7/27%20budget%20challenge%20a aron/0727_budget_challenge_aaron Leonard Burman, et. al. “Catastrophic Budget Failure,” paper presented to the Conference on America’s Looming Fiscal Crisis, Los Angeles, January 15, 2010 http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/1001564-CBF-NTJ.pdf Committee for Economic Development, Quality, Affordable Health Care For All http://www.ced.org/images/library/reports/health_care/report_healthcare07.pdf Suggested Reading: Paul Posner and Irene Rubin, “Budgeting for the Long Term.” GAO, Accrual Budgeting: Useful in Certain Areas But Does Not Provide Sufficient Information for Reporting on the Nation’s Long Term Fiscal Challenge, GAO-08-206, 2007. GAO, Fiscal Exposures: Improving the Budgetary Focus on Long-Term Costs and Uncertainties, GAO-03-213 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 24, 2003). Alan M. Jacobs, “The Politics of When: Redistribution, Investment and Policy Making for the Long Term,” British Journal of Political Science 38 (2008), pp. 193-220. R. Douglas Arnold, “The Politics of Reforming Social Security,” Political Science Quarterly Volume 113 Number 2 1998 – Blackboard Lecture 5, February 22 – Not All Money Is Green: Earmarked Revenues, Trust Funds And User Fees We will learn this week about the special challenges associated with budgeting for capital, feefunded programs and earmarked revenues. Advocates for these kinds of programs have perennially attempted to recognize the different character of these kinds of programs by providing for differential treatment in the budget process. This session will discuss the unique issues associated with each, and will explore the implications of such solutions as capital budgets, trust funds and offsetting collections for the politics and outcomes of budgeting. High-Priority Reading: 6 OMB, Analytical Perspectives, FY 2017, Chapters on “Offsetting Collections and Offsetting Receipts,” “Federal Investment,” “Federal Research and Development,” and “Trust Funds and Federal Funds” GAO, Federal Trust Funds and Other Earmarked Funds: Frequently Asked Questions (GAO-01-199SP) Suggested Reading: Sita Nataraj and John B. Shoven, Has The Unified Budget Undermined The Federal Government Trust Funds? – http://www.nber.org/programs/ag/rrc/04-02ShovenDraftWP1.pdf GAO, Federal User Fees: Key Considerations for Designing and Implementing Regulatory Fees, 2015, GAO-15-718 Assignment due on the date of Lecture 6: Write a two-page memo for your boss in Congress: Is the Social Security Trust Fund accounting system a good institution? What, if anything, should we do to change it? Lecture 6, February 29 – The Politics and Process of Taxation Discussion will focus on the composition of revenues, the implications of tax policy for economic outcomes and for budgetary choices. Tax expenditures are among the issues that will be considered. High-Priority Reading: Bipartisan Policy Center, Restoring America’s Future http://bipartisanpolicy.org/sites/default/files/BPC%20FINAL%20REPORT%20FOR%20PRINTER%2 002%2028%2011.pdf (section on taxation) Joseph J. Minarik, “Taxation,” The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Taxation.html Joseph J. Minarik, “How Tax Reform Came About,” on Blackboard Allen Schick, Federal Budget – Chapter 7 U.S. GAO, Understanding the Tax Reform Debate (GAO-05-1009SP) Suggested Reading: Sheldon Pollack, The Politics of Taxation – http://www.buec.udel.edu/pollacks/Downloaded%20SDP%20articles,%20etc/professional%20activ ities/APSA-98.pdf U.S. GAO, Government Performance and Accountability: Tax Expenditures Represent a Substantial Federal Commitment and Need to be Reexamined, (GAO-05-690) SPRING BREAK, MARCH 7 – NO CLASS Lecture 7, March 14 – Student Presentations Teams of students will be asked to interpret for the class trends in the following areas: 7 --Revenues over the past 50 years --Defense spending over the past 50 years --Health care spending over the past 50 years --Federal investment spending over the past 50 years --Grants to state and local governments over past 50 years --Income security over past 50 years --Federal civil servant pay and benefits over past 50 years Using the OMB Historical Tables, CBO reports and other sources, groups of students will explain for the class the trends in nominal and real numbers as well as provide other perspectives helping to explain reasons for the trends. THE MID-TERM EXAM WILL BE DISTRIBUTED ON THE DATE OF LECTURE 8, TO BE RETURNED BEFORE CLASS ON THE DATE OF LECTURE 9 Lecture 8, March 21 – The Crucible of Politics Assessment of the political underpinnings of budgeting by exploring political trends in national government institutions, political parties, interest groups, the media, and cultural and social interests. The results of these trends will be linked to current pressures on the federal budget. Models will also be presented that seek to link dimensions of political debates and interests with policy outcomes. High-Priority Reading: Allen Schick, The Federal Budget: Politics, Policy and Process – Chapters 1 and 2. Hugh Heclo, “Hyperdemocracy” – Blackboard Anthony Downs, “Why the Government Budget is Too Small in a Democracy” – Blackboard “Origins of the Debt Showdown,” Washington Post, August 6, 2011 http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/origins-of-the-debtshowdown/2011/08/03/gIQA9uqIzI_story.html?hpid=z1 Paul Posner, Will It Take A Crisis, Pew Foundation, March, 2011 http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Reports/Economic_Mobility/PosnerWill-it-Take-a-Crisis.pdf Standard and Poor’s downgrading of U.S. Treasuries from AAA to AA+ http://www.standardandpoors.com/ratings/articles/en/us/?assetID=1245316529563 Suggested Reading: Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “Deficit Reduction: Lessons From Around the World,” (Washington, D.C., September, 2009) 8 Jens Henriksson, “Ten Lessons About Budget Consolidation” (Brussels: Bruegel Essay and Lecture Series, 2007) – Blackboard Lecture 9, March 28 – Performance Budgeting and Accountability; Capital Budgeting Discussion will focus on how budgets impact performance and implementation of programs. Discuss approaches over the years to introduce performance assessments and measures into budgeting. Discuss how agencies manage funds after appropriations are enacted. Oversight, audit and evaluation will also be addressed. High-Priority Readings: GAO, Budget Issues: Budgeting for Federal Capital, 1996, GAO/AIMD-97-5 Allen Schick, Federal Budget, Chapter 10 Suggested readings: CBO, Comparing Budget and Accounting Measures of the Federal Government’s Financial Condition, December, 2006 Allen Schick, “The Road to PPB: Stages of Budget Reform” – Public Administration Review, December, 1966 – Blackboard OMB, Analytical Perspectives, FY 2017, Chapters on “Program Evaluation and Data Analytics” and “Benefit-Cost Analysis” GAO, Executive Guide: Leading Practices in Capital Decision-Making. GAO/AIMD-99-32. December 1998 President’s Commission to Study Capital Budgeting Report, 1999 (http://clinton2.nara.gov/pcscb/report.pdf). Paul L. Posner, Public-Private Partnerships: The Relevance of Budgeting, paper presented at OECD Senior Budget Officers meeting, 2008 – Blackboard Lecture 10, April 4 – The Process and Politics of Budget Formulation: The Executive Branch; Microbudgeting: Appropriations and the Structure of the Federal Budget Process This topic will focus on the process of budget formulation – from both agency and central budget office perspectives. Discussion will first center on the role and nature of the formal institutions involved with budget formulation, including processes, requirements and submissions. Students will become familiar with the OMB Circular A-11 – the basic guidance to agencies to formulate their requests. The discussion will then proceed to explore the politics behind the process – what are the incentives faced by the various players in the process and what are some of the strategies they pursue? Discussion will include the concepts underlying the preparation of the federal budget, including budget baselines, budget accounts, functions, character class codes and object classes. The basic fundamentals about tracking federal expenditures through the process will be covered. Various kinds of budget authorities will be covered, including discretionary, mandatory, contract. Trust funds and federal funds will also be covered. Student teams will report back on their work on budget formulation, with presentations on the FAA, DOT and OMB roles and actions. 9 High-Priority Readings: U.S. GAO, A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process (GAO-05-734SP) – read appendices U.S. OMB, Historical Tables, FY 2017 Budget Allen Schick, Federal Budget, Chapters 3, 4 and 5 James True, Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones, “Policy Punctuations: U.S. Budget Authority, 1947-1995” – Blackboard Joseph White, “Entitlement Budgeting versus Bureau Budgeting” – Blackboard Charles Levine, “Organizational Decline and Cutback Management,” Public Administration Review – Blackboard Suggested Reading: R. Kent Weaver, “The Politics of Blame Avoidance” Journal of Public Policy (1986), 6: 371-398 – Blackboard Charles Lindblom, “The science of muddling through,” Public Administration Review, 1959 http://www.archonfung.net/docs/temp/LindblomMuddlingThrough1959.pdf Lecture 11, November 23 – The Role of the Congress Discussion will focus on the Congressional budget and appropriations processes. How does Congress formulate its own budget goals and how do the various institutions within Congress work to either support or undermine the process? The discussion will focus on appropriations committees and their roles in the process, as well as on authorization committees. High-Priority Readings: Allen Schick, Federal Budget, Chapters 6, 8 and 9 Gary Jacobson, “Deficit Cutting Politics and Congressional Elections,” Political Science Quarterly 108, no. 3 (1993): 375-402 – Blackboard Jonathan Rauch, “Divided We Thrive,” New York Times, November 14, 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/07/opinion/07rauch.html Suggested Readings: James Saturno, “Points of Order in the Congressional Budget Process” - Blackboard Philip Joyce, “Congressional budget reform: The unanticipated implications for federal policy making,” Public Administration Review, Washington: Jul/Aug 1996. Vol. 56, Iss. 4 – Blackboard ASSIGNMENT DUE ON THE DATE OF LECTURE 12 – You are the budget adviser to the head of a federal agency (you choose which one – an entire department, or an agency within a department, or an independent agency). Write a two-page memo to your boss to prepare him or her for budget formulation and submission. Explain the mission of your agency; explain 10 its strengths and its weaknesses; identify it allies and enemies in the competition for budget funding; recount its recent budget history; and recommend goals for the new budget submission. Lecture 12, April 18 - Budget Process and Reforms When groups don’t like the outcomes of the budget process, they sometimes reach for budget process reforms to change the results. In this session, we will inventory the types of process reforms, understand their prospective impacts and explore the political prospects of serious reform to the budget system at the national level. High-Priority Readings: Paul Posner, “Budget Process Reform: Waiting for Godot,” Public Administration Review, March/April, 2009 – Blackboard Aaron Wildavsky, “The Political Implications of Budget Reform: A Retrospective” – Blackboard Allen Schick, Federal Budget, Chapter 11 Getting Back to Black, Report of Pew-Peterson Commission on Budget Process Reform, November, 2010 – Blackboard Suggested Readings: Heritage Foundation, “10 Elements of Comprehensive Budget Process Reform, 2006” – Blackboard Philip Joyce and Robert Reischauer, “The Federal Line Item Veto: What it is and what it will do,” Public Administration Review, Vol 57, No. 2 (March/April, 1997) – Blackboard Irene Rubin, “The Great Unraveling: Federal Budgeting, 1998-2006” Public Administration Review, July/August, 2007, Vol 67, Issue 4 – Blackboard Lecture 13, April 25 – Intergovernmental Fiscal Relationships; the Obama Stimulus and the States Federal budgeting is not only about federal agencies and their employees but also entails a range of other subsidies and tools providing subsidies, grants and loans to state and local governments and other nonprofit and private for-profit entities. State and local governments and the national government often jointly participate in financing public services through grants, loans and tax expenditures as well as mandates. This discussion will examine federal budgeting for intergovernmental programs and understand the implications for federal and state and local finances and accountability to common taxpayers. We will assess whether the politics of federal budgeting varies significantly for different tools of governance and how this manifests itself in federal program design and implementation. High-Priority Readings: Timothy Conlan, “The Politics of Federal Grants,” Political Science Quarterly – Blackboard GAO, State and Local Governments: Persistent Fiscal Challenges, GAO-07-1080SP, July, 2007 OMB, Analytical Perspectives FY 2017, Chapter on “Aid to State and Local Governments” 11 Robert D. Lee, Public Budget Systems, Chapter 14 Suggested Reading: David Firestone, “Don’t Tell Anyone, But the Stimulus Worked,” New York Times (http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/16/opinion/sunday/dont-tell-anyone-but-the-stimulusworked.html) Alan S. Blinder and Mark Zandi, “How the Great Recession Was Brought to an End” – Blackboard – and criticism on e21 (http://economics21.org/blog/economists-say-interventionhelped-how-much) Lecture 14, May 2 – Reserve for inclement weather makeup, special topics, review FINAL EXAM – Will be distributed electronically at a mutually agreed upon time after the end of Lecture 14, to be returned one week later. 12