Copyright Registrations

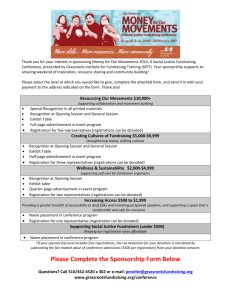

advertisement