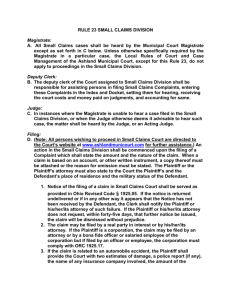

485 RULE 68 - Sturm College of Law

advertisement