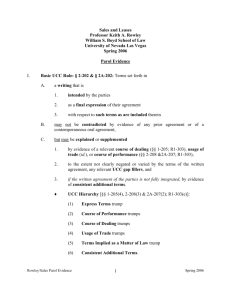

the convention on contracts for the international sale of goods in

advertisement