SETTLEMENT OF MAJOR HEALTHCARE FRAUD

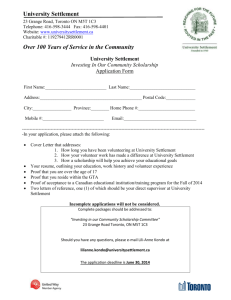

advertisement