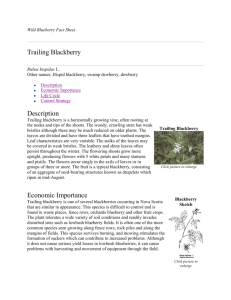

Blackberry control manual - Victorian Blackberry Taskforce

advertisement