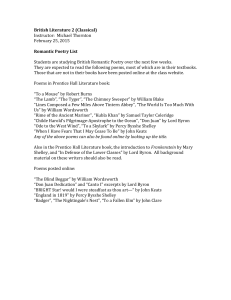

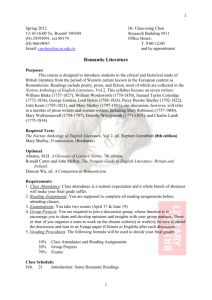

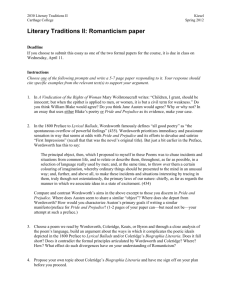

The Romantics and Their Contemporaries

advertisement