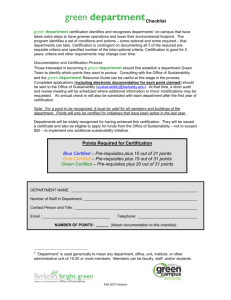

Corporate Sustainability Initiative

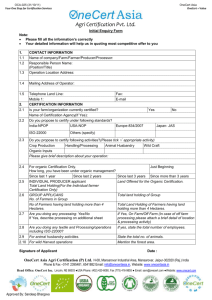

advertisement