Poor People Lose: Gideon and the Critique of Rights

advertisement

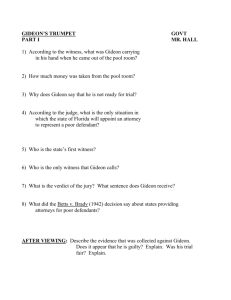

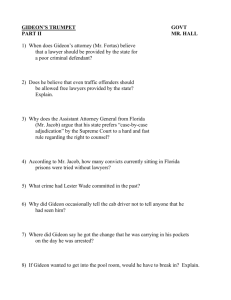

2176.BUTLER.2204_UPDATED.DOCX7/1/2013 12:28:47 PM Paul D. Butler Poor People Lose: Gideon and the Critique of Rights abstract. A low income person is more likely to be prosecuted and imprisoned post-Gideon than pre-Gideon. Poor people lose in American criminal justice not because they have ineffective lawyers but because they are selectively targeted by police, prosecutors, and law makers. The critique of rights suggests that rights are indeterminate and regressive. Gideon demonstrates this critique: it has not improved the situation of most poor people, and in some ways has worsened their plight. Gideon provides a degree of legitimacy for the status quo. Even full enforcement of Gideon would not significantly improve the loser status of low-income people in American criminal justice. author. Professor, Georgetown University Law Center; Yale College, B.A.; Harvard Law School, J.D. For helpful comments on this Essay, I thank Kristin Henning, Allegra McLeod, Gary Peller, Louis Michael Seidman, Abbe Smith, Robin West, and the participants in a faculty workshop at Florida State University College of Law. I am also grateful for the excellent editorial assistance of Robert Quigley, Yale Law School, J.D. 2014. 2176 poor people lose essay contents introduction 2178 i. how poor people lose in american criminal justice 2179 ii. the critique of rights 2187 iii. the critique of rights, applied to gideon 2190 A. The Liberal Overinvestment in Rights B. The Indeterminacy of Rights C. Rights Discourse and Mystification D. Isolated Individualism E. Rights Discourse as an Impediment to Progressive Social Movements 2190 2192 2194 2195 2196 iv. other comments on rights discourse in criminal procedure 2198 conclusion: critical tactics 2201 2177 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 introduction Gideon v. Wainwright1 is widely regarded as a milestone in American criminal justice. When it was decided in 1963, it was seen as a major step forward in assuring fairness to poor people and racial minorities. Yet, fifty years later, low-income and African-American people in the criminal justice system are considerably worse off. It would be preferable to be a poor black charged with a crime in 1962 than now, if one’s objective is to avoid prison or serve as little time as possible. The “critique of rights,” as articulated by critical legal theorists, posits that “nothing whatever follows from a court’s adoption of some legal rule”2 and that “winning a legal victory can actually impede further progressive change.”3 My thesis is that Gideon demonstrates the critique of rights. Arguably, Gideon has not improved the situation of accused persons, and may even have worsened their plight. The reason that prisons are filled with poor people, and that rich people rarely go to prison, is not because the rich have better lawyers than the poor. It is because prison is for the poor, and not the rich. In criminal cases poor people lose most of the time, not because indigent defense is inadequately funded, although it is, and not because defense attorneys for poor people are ineffective, although some are. Poor people lose, most of the time, because in American criminal justice, poor people are losers. Prison is designed for them. This is the real crisis of indigent defense. Gideon obscures this reality, and in this sense stands in the way of the political mobilization that will be required to transform criminal justice. I know that, for some readers, these claims are counterintuitive, and I ask these readers’ indulgence for the time it takes to read this Essay, in which I will attempt to prove my claims. It is also important to emphasize that I am not making a “but-for” claim of causation. Gideon is not responsible for the exponential increase in incarceration or the vast rise in racial disparities in criminal justice. As I explain later, however, Gideon bears some responsibility for legitimating these developments and diffusing political resistance to them. It invests the criminal justice system with a veneer of impartiality and 1. 2. 3. 327 U.S. 335 (1963). Mark Tushnet, The Critique of Rights, 47 SMU L. REV. 23, 32 (1993). Tushnet refers to this component of the critique of rights as the “indeterminacy thesis.” Id. at 26. 2178 poor people lose respectability that it does not deserve. Gideon created the false consciousness that criminal justice would get better. It actually got worse. Even full enforcement of Gideon would not significantly improve the wretchedness of American criminal justice. In Lafler v. Cooper4 and Missouri v. Frye,5 the Supreme Court extended the right to counsel to the plea bargaining stage of prosecution. Some people are having a Gideon moment6: the Court’s rulings seem like important victories for indigent accused persons because, as Justice Kennedy observed in Lafler, “criminal justice today is for the most part a system of pleas, not a system of trials.”7 It seems cynical and defeatist to recall Mark Tushnet’s observation that “nothing whatever follows from a court’s adoption of some legal rule.”8 But one goal of this Essay is to disrupt the “cruel optimism” that Gideon discourse creates. This Essay proceeds as follows. The first Part develops the claim that the poor—especially poor African Americans—are “losers” in American criminal justice and that providing them with more, or better, defense attorneys would not substantially alter their subordination. Part II describes the critique of rights, and Part III applies it to Gideon. Part IV compares the critique of rights to other comments on rights discourse in criminal procedure. The Essay concludes with some recommendations on what advocates for poor people might do that would help them more than discoursing about rights. i. how poor people lose in american criminal justice Indigent persons are much more likely to go to prison today than in the era when Gideon was decided. In 1960, the U.S. imprisonment rate was approximately 126 per 100,000 population.9 By, 2008, the rate had quadrupled, 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 132 S. Ct. 1376 (2012). 132 S. Ct. 1399 (2012). See Adam Liptak, Justices’ Ruling Expands Rights of Accused in Plea Bargains, N.Y. TIMES, Mar. 21, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/22/us/supreme-court-says-defendants -have-right-to-good-lawyers.html. 132 S. Ct. at 1388. Tushnet, supra note 2, at 32. Margaret Werner Cahalan, Historical Corrections Statistics in the United States, 1850-1984, BUREAU OF JUST. STAT. 30 (1986), https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/pr/102529.pdf. 2179 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 to 504 per 100,000.10 African-American defendants are even worse off. In 1960, three years before Gideon, the black incarceration rate was approximately 660 per 100,000.11 By 1970, it had fallen some, to slightly under 600 per 100,000.12 In 2010, the rate of incarceration among black males was an astronomical 3,074 per 100,000.13 For men hoping to avoid prison, being both poor and black is a lethal combination. More than two-thirds of black males who do not have college degrees will be incarcerated at some point in their lives.14 Black male high school dropouts are more likely to be imprisoned than employed.15 What is it about being poor and African American that substantially increases the risk of incarceration? The answer, rather obviously, has much to do with class and race and, less obviously, little to do with the quality of the indigent defense system. This Essay employs data about both race and class to demonstrate this claim, but at the start I want to note that it is impossible to disaggregate the effects of race and class. The answer to the questions, “Are poor defendants treated unfairly because many of them are black, are black defendants treated unfairly because many of them are poor, or is there some other dynamic at work?” is “yes.”16 Indeed, the Gideon decision itself was William J. Sabol, Heather C. West & Matthew Cooper, Prisoners in 2008, BUREAU OF JUST. STAT. 6 (2009), http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/p08.pdf. 11. See Margaret Cahalan, Trends in Incarceration in the United States Since 1880: A Summary of Reported Rates and the Distribution of Offenses, 25 CRIME & DELINQUENCY 9, 40 tbl.11 (1979) (reporting that there were 125,000 black adult inmates in the U.S. in 1960); Race for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States: 1960, U.S. CENSUS BUREAU (2002), http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0056/tabA-08.pdf (stating that the U.S. black population in 1960 was 18,871,831). 12. See Cahalan, supra note 11, at 40 tbl.11 (reporting that 134,000 black adult inmates in the U.S. in 1970); Race for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States: 1970, U.S. CENSUS BUREAU (2002), http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0056/tabA -05.pdf (stating that the U.S. black population in 1970 was 22,580,289). 13. Paul Guerino, Paige M. Harrison & William J. Sabol, Prisoners in 2010, BUREAU OF JUST. STAT. 27 (2010), http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/p10.pdf. 10. Bruce Western & Becky Pettit, Incarceration and Social Inequality, DAEDALUS, Summer 2010, at 8, 16. 15. Id. at 12. 16. For a discussion of the problems and benefits of analyzing modalities of subordination, see Kimberle Crenshaw, Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, 1989 U. CHI. LEGAL F. 139, 166-67; and Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Race, Reform and Retrenchment: 14. 2180 poor people lose explicitly a class intervention, but implicitly, like other Warren court criminal procedure cases, a racial justice intervention as well.17 Approximately two decades after Gideon, two trends began in criminal justice, the effects of which were to overwhelm any benefits that Gideon provided to low-income accused persons. First, the United States experienced the most pronounced increase in incarceration in the history of the world.18 Second, there was a corresponding exponential increase in racial disparities in incarceration. This dramatic expansion of incarceration was accomplished on the backs of poor people. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that the “generally accepted indigency rate” for state felony cases near the time when Gideon was decided was 43%.19 Today approximately 80% of people charged with crime are poor.20 Other data further illustrate the correlation between poverty and incarceration. In 1997, more than half of state prisoners earned less than $1,000 in the month before their arrest.21 This would result in an annual income of less than $12,000, well below the $25,654 median per capita income in 1997.22 The same year, 35% of state inmates were unemployed in the month before their arrest, compared to the national unemployment rate of 4.9%.23 Approximately 70% of state prisoners have not graduated from high Transformation and Legitimation in Antidiscrimination Law, 101 HARV. L. REV. 1331 (1988) [hereinafter Crenshaw, Race, Reform and Retrenchment]. 17. See JOHN HART ELY, DEMOCRACY AND DISTRUST 97 (1980); Michael J. Klarman, The Puzzling Resistance to Political Process Theory, 77 VA. L. REV. 747, 763-66 (1991); Carol S. Steiker, Second Thoughts about First Principles, 107 HARV. L. REV. 820, 838-52 (1994); see also William J. Stuntz, The Uneasy Relationship Between Criminal Procedure and Criminal Justice, 107 YALE L.J. 1, 5 (1997) (“Warren-era constitutional criminal procedure began as a kind of antidiscrimination law.”). 18. See Adam Gopnik, The Caging of America: Why Do We Lock Up So Many People?, NEW YORKER, Jan. 30, 2012, http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2012/01/30 /120130crat_atlarge_gopnik (“Mass incarceration on a scale almost unexampled in human history is a fundamental fact of our country today . . . .”). 19. Stuntz, supra note 17, at 7 n.7. Mary Sue Backus & Paul Marcus, The Right to Counsel in Criminal Cases, A National Crisis, 57 HASTINGS L.J. 1031, 1034 (2006). 21. Caroline Wolf Harlow, Education and Correctional Populations, BUREAU OF JUST. STAT. 1, 10 & tbl.14 (2003), http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/ecp.pdf. 22. Per Capita Personal Income by State, BUREAU OF BUS. & ECON. RES., http://bber.unm.edu /econ/us-pci.htm (last visited Mar. 29, 2013). 23. Harlow, supra note 21, at 1, 10. 20. 2181 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 school.24 Only 13% of incarcerated adults have any post-high school education, compared with almost 50% of the non-incarcerated population.25 College graduation, on the other hand, serves to insulate Americans from incarceration. Only 0.1% of bachelor’s degree holders are incarcerated, compared to 6.3% of high school dropouts.26 Put another way, high school dropouts are sixty-three times more likely to be locked up than college graduates. The post-Gideon expansion of the prison population was also accomplished on the backs of black people. There have been always been racial disparities in American criminal justice, but from the 1920s through the 1970s they were “only” about two-to-one.27 Now the black/white incarceration disparity is seven-to-one.28 There are more African Americans under correctional supervision than there were slaves in 1850.29 As Michelle Alexander states, “If mass incarceration is considered as a system of social control—specifically, racial control—then the system is a fantastic success.”30 In summary, poor people and blacks have never fared as well as the nonpoor and the nonblack in American criminal justice. Since the 1970s, however, the disparities have gotten much worse. Something happened that dramatically increased incarceration and dramatically raised the percentage of the incarcerated who are poor and black. What happened is usually attributed to two main causes: the war on drugs and the law-and-order or so-called tough-on-crime policies of American leaders since the Nixon Administration.31 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Id. at 1. Id. at 1-2 & tbl.1. Andrew Sum, Ishwar Khatiwada & Joseph McLaughlin, The Consequences of Dropping Out of High School: Joblessness and Jailing for High School Dropouts and the High Cost for Taxpayers 10 (Ctr. for Labor Mkt. Studies Publ’ns, Paper No. 23, 2009), http://hdl.handle.net /2047/d20000596. Pamela E. Oliver & Marino A. Bruce, Tracking the Causes and Consequences of Racial Disparities in Imprisonment 2-3 (2001) (unpublished project proposal to the National Science Foundation), http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~oliver/RACIAL/Reports /nsfAug01narrative.pdf. Heather C. West, Prison Inmates at Midyear 2009—Statistical Tables, BUREAU OF JUST. STAT. 21 tbl.18 (2010), http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/pim09st.pdf. MICHELLE ALEXANDER, THE NEW JIM CROW: MASS INCARCERATION IN THE AGE OF COLORBLINDNESS 271 n.7 (2010). Id. at 225. See id. at 271 n.7; see also WILLIAM J. STUNTZ, THE COLLAPSE OF AMERICAN CRIMINAL JUSTICE 136 (2011) (describing the period between Reconstruction and the Great Depression, and 2182 poor people lose Thus far I have made the case that prisons are populated by people who are disproportionately poor and African American. My next step is to demonstrate that this is not a coincidence, in order to further support the claim that the poor are losers in American criminal justice. Mass incarceration’s process of control—the social and legal apparatus by which poor people become losers in criminal justice—can be broken into five steps. (1) The spaces that poor people, especially poor African Americans, live in receive more law enforcement in the form of police stops and arrests.32 (2) The criminal law deliberately ignores the social conditions that breed some forms of law-breaking.33 Deprivations associated with poverty are usually not “defenses” to criminal liability, although they may be factors considered in sentencing. (3) African Americans, who are disproportionately poor, are the target of explicit and implicit bias by key actors in the criminal justice system, including police, prosecutors,34 and judges.35 noting that “racial bias, though real and powerful, was . . . weaker than one might imagine” and that “nothing comparable to the massive racial tilt in today’s drug prisoner population existed in the Gilded Age North”). 32. See Lawrence D. Bobo & Victor Thompson, Unfair by Design: The War on Drugs, Race, and the Legitimacy of the Criminal Justice System, 73 SOC. RES. 445 (2006); Tracey Meares, Place and Crime, 73 CHI.-KENT L. REV. 669 (1998). For an argument that the African-American community actually benefits from more law enforcement, see RANDALL KENNEDY, RACE, CRIME, AND THE LAW (1997), and for a critique of this argument, see Paul Butler, (Color) Blind Faith: The Tragedy of Race, Crime, and the Law, 111 HARV. L. REV. 1270 (1998) (reviewing KENNEDY, supra). 33. See BRUCE WESTERN, PUNISHMENT AND INEQUALITY IN AMERICA (2006); Richard Delgado, “Rotten Social Background”: Should the Criminal Law Recognize a Defense of Severe Environmental Deprivation?, 3 LAW & INEQUALITY 9, 9-10 (1985); see also Jones v. City of Los Angeles, 444 F.3d 1118, 1120 (9th Cir. 2006) (holding unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment a Los Angeles ordinance criminalizing “sitting, lying, or sleeping on public streets and sidewalks at all times and in all places”), vacated because of settlement, 505 F.3d 1006 (2007); United States v. Alexander, 471 F.2d 923, 957-65 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (Bazelon, C.J., dissenting) (arguing that a “rotten social background” defense and corresponding jury instruction may be appropriate in some cases). 34. See ANGELA J. DAVIS, ARBITRARY JUSTICE: THE POWER OF THE AMERICAN PROSECUTOR 3-42 (1997). 2183 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 (4) Once any person is arrested, she becomes part of a crime control system of criminal justice, in which guilt is presumed.36 Prosecutors, using the legal apparatus of expansive criminal liability, recidivist statutes, and mandatory minimums,37 coerce guilty pleas by threatening defendants with vastly disproportionate punishment if they go to trial.38 (5) Repeat the cycle. A criminal caste is created. Two-thirds of freed prisoners are rearrested, and half return to prison, within three years of 35. Prosecutors are more likely to charge black suspects than whites, even controlling for factors like prior criminal record. See Robert J. Smith & Justin D. Levinson, The Impact of Implicit Racial Bias on the Exercise of Prosecutorial Discretion, 35 SEATTLE U. L. REV. 795, 806 (2012). While African Americans do not disproportionately use or sell drugs, they are over one-third of those arrested for drug crimes. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, DECADES OF DISPARITY: DRUG ARRESTS AND RACE IN THE UNITED STATES 4 (2009); HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, TARGETING BLACKS: DRUG ENFORCEMENT AND RACE IN THE UNITED STATES 3, 41-44 (2008). Research on implicit bias suggests that blacks are more likely to be suspected of crime, convicted, and punished for longer than others. For a summary of this research, see Smith & Levinson, supra, at 800-01; see also ALEXANDER, supra note 29, at 103-05 (surveying research on racial bias and criticizing the Supreme Court for “adopting rules that would maximize—not minimize—the amount of racial discrimination that would likely occur”). 36. Herbert L. Packer, Two Models of the Criminal Process, 113 U. PA. L. REV. 1, 11 (1964). 37. The Supreme Court has blessed this practice. In Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 U.S. 357 (1978), Paul Hayes was charged with uttering a forged instrument in the amount of $88.30. The maximum sentence for the offense was ten years, and the prosecutor offered to recommend a five-year sentence in exchange for a guilty plea. The prosecutor also indicated that if there was no guilty plea, he would charge Mr. Hayes under a recidivist statute that would require a life sentence if Mr. Hayes was convicted. Mr. Hayes turned down the plea, the prosecutor won his conviction, and Mr. Hayes received a life sentence. Id. at 358-59. The Supreme Court found no constitutional violation, although it stated that “the breadth of discretion that our country’s legal system vests in prosecuting attorneys carries with it the potential for both individual and institutional abuse.” Id. at 365. For a powerful critique of prosecutorial abuse of discretion in the plea-bargaining process, see Jonathan A. Rapping, Who’s Guarding the Henhouse? How the American Prosecutor Came To Devour Those He Is Sworn To Protect, 51 WASHBURN L.J. 513 (2012). 38. John H. Langbein, Torture and Plea Bargaining, 46 U. CHI. L. REV. 3, 18 (1978) (“The modern public prosecutor commands the vast resources of the state for gathering and generating accusing evidence. We allowed him this power in large part because the criminal trial interposed the safeguard of adjudication against the danger that he might bring those resources to bear against an innocent citizen—whether on account of honest error, arbitrariness, or worse. But the plea bargaining system has largely dissolved that safeguard.”). 2184 poor people lose their release.39 This description is not intended to be novel, or especially provocative. Other observers of American criminal justice have made similar points about the process by which being poor and African American increases the risk of incarceration. Richard S. Frase, for example, writes that poverty and lack of opportunity are associated with higher crime rates; crime leads to arrest, a criminal record, and usually a jail or prison sentence; past crimes lengthen those sentences; offenders released from prison or jail confront family and neighborhood dysfunction, increased risks of unemployment, and other crime-producing disadvantages; this make them likelier to commit new crimes, and the cycle repeats itself.40 Michelle Alexander notes: It is simply taken for granted that, in cities like Baltimore and Chicago, the vast majority of young black men are currently under the control of the criminal justice system or branded criminals for life. This extraordinary circumstance—unheard of in the rest of the world—is treated here in America as a basic fact of life, as normal as separate water fountains were just a half century ago.41 What if every person accused of a crime had an excellent lawyer? Proponents of Gideon suggest it would be an important step in making criminal justice more equitable. For example, David Cole writes that the “story of the enforcement of the right to counsel suggests that our failure to make good on Gideon’s promise is no mere mistake. Rather, it is the single most important mechanism by which the courts and society ensure a double standard in constitutional rights protection in the criminal law.”42 In reality, full enforcement of Gideon probably would not significantly impact the “double standard.” If mass incarceration and racial disparities were caused by poor defense attorneys, it would make sense to think of Gideon as the Patrick A. Langan & David J. Levin, Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994, BUREAU OF JUST. STAT. 7 tbl.8 (2002), http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/rpr94.pdf. 40. Richard S. Frase, What Explains Persistent Racial Disproportionality in Minnesota’s Prison and Jail Populations?, 38 CRIME & JUST. 201, 263 (2009). 41. ALEXANDER, supra note 29, at 176. 42. DAVID COLE, NO EQUAL JUSTICE 65 (1999). 39. 2185 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 appropriate solution. But, as the five-step process described above demonstrates, defenders are not the cause. I want to be careful not to discount the difference that an excellent defense attorney can make, and how much this matters for individual clients. At the same time, I don’t want to overclaim, as I believe Professor Cole does, that full enforcement of Gideon would bring anything remotely resembling equality to American criminal justice. Empirical evidence of whether attorney ability makes a difference in trial outcomes is inconclusive. An important study by James M. Anderson and Paul Heaton suggests that public defenders in Philadelphia, compared to appointed counsel, “reduce their clients’ murder conviction rate by 19%. They reduce the probability that their clients receive a life sentence by 62%. Public defenders reduce overall time served in prison by 24%.”43 Another study by David Abrams and Albert Yoon suggests that “going from the tenth to ninetieth percentile of public defender ability decreases the defendant’s expected sentence length by 5.8 months. . . . Clearly, the public defender to whom a defendant is assigned . . . has a significant impact on how much time the defendant will serve.”44 But another empirical study found that “the skill level of the defense attorney plays no role in determining the outcome of a criminal trial in everyday cases with non-celebrity defendants.”45 There is indirect evidence from courts that the scale of punishment of the poor would not be reduced by more effective lawyers. In Strickland v. Washington, the Supreme Court established a two-pronged test to determine ineffective assistance of counsel.46 First, the counsel’s representation must fall below an “objective standard of reasonableness.”47 Second, there must be a “reasonable probability that, but for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different.”48 In practice the tests rarely leads to a finding of ineffectiveness. I do not want to suggest that the Strickland test is the appropriate measure of effective 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. James M. Anderson & Paul Heaton, How Much Difference Does the Lawyer Make? The Effect of Defense Counsel on Murder Case Outcomes, 122 YALE L.J. 154, 159 (2012). David S. Abrams & Albert H. Yoon, The Luck of the Draw: Using Random Case Assignment To Investigate Attorney Ability, 74 U. CHI. L. REV. 1145, 1166-67 (2007). Jennifer Bennett Shinall, Note, Slipping Away from Justice: The Effect of Attorney Skill on Trial Outcomes, 63 VAND. L. REV. 267, 291 (2010). 466 U.S. 668 (1984). Id. at 688. Id. at 694. 2186 poor people lose assistance.49 I do want to suggest, however, that courts are probably correctly applying the test. As stated above, the most favorable empirical evidence suggests that more able defenders reduce average sentences by 24%. For individual defendants, this reduction is very important. But even with a 24% reduction in every sentence, American criminal justice would remain the harshest and most punitive in the world. The poor, and especially poor people of color, are its primary victims. ii. the critique of rights 50 Robin West has described the critique of rights as “one of the most vibrant, important, counterintuitive, challenging set of ideas that emerged from the legal academy over the course of the last quarter of the twentieth century.”51 Many of these ideas were articulated as part of the critical legal studies movement that began in the 1980s.52 In a seminal 1984 article, Mark Tushnet described rights as unstable, indeterminate, overly abstract, and politically harmful to the Left.53 The critique of rights was intended as an “act of creative destruction that may help us build societies that transcend the failures of 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. According to the National Right to Counsel Committee, a blue-ribbon panel that evaluated the indigent counsel system, “Since Strickland was decided, commentators have been virtually unanimous in their criticisms of the opinion.” NAT’L RIGHT TO COUNSEL COMM., CONSTITUTION PROJECT, JUSTICE DENIED: AMERICA’S CONTINUING NEGLECT OF OUR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT TO COUNSEL 40-41 (2009), http://www.constitutionproject.org /pdf/139.pdf. The critiques of Strickland have focused on the difficulty defendants have in proving that their cases would have come out differently had their lawyers performed better. Courts usually hold that they would not have. For seminal texts making the critique of rights, see Peter Gabel, The Phenomenology of RightsConsciousness and the Pact of the Withdrawn Selves, 62 TEX. L. REV. 1563 (1984); Duncan Kennedy, The Critique of Rights in Critical Legal Studies, in LEFT LEGALISM/LEFT CRITIQUE 178 (Wendy Brown & Janet Halley eds., 2002); and Mark Tushnet, An Essay on Rights, 62 TEX. L. REV. 1363 (1984). Robin L. West, Tragic Rights: The Rights Critique in the Age of Obama, 53 WM. & MARY L. REV. 713, 715 (2011). For a longer description and intellectual history of the critique of rights, see Kennedy, supra note 50. Tushnet, supra note 50, at 1363-64. Tushnet’s critique was contextual, i.e., based on how rights function in the United States. He observed: “[T]here is nothing odd about saying that rights in Poland are a good thing, while rights in the United States are not. They are, after all, different cultures.” Id. at 1382. 2187 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 capitalism.”54 The critique of rights has evolved to many sets of critiques.55 One description on a website curated by a group of legal theorists who teach or have taught at Harvard Law School summarizes five basic elements: (1) The discourse of rights is less useful in securing progressive social change than liberal theorists and politicians assume. (2) Legal rights are in fact indeterminate and incoherent. (3) The use of rights discourse stunts human imagination and mystifies people about how law really works. (4) At least as prevailing in American law, the discourse of rights reflects and produces a kind of isolated individualism that hinders social solidarity and genuine human connection. (5) Rights discourse can actually impede progressive movement for genuine democracy and justice.56 Most of the critiques make the claim that rights are indeterminate. The proposition is that “the law is not a fixed and determined system, but rather an unruly miscellany of various, multifaceted, contradictory practices, altering from time to time and from context to context as different facets of law are privileged or suppressed.”57 Robin West describes the indeterminacy thesis as meaning that “the articulation of an interest as a ‘right’ by no means creates an unmoveable bulwark against change, interference, or recalibration of the protection of the various interests . . . toward which it so desperately strives.”58 54. Id. at 1363 (footnote omitted). See, e.g., West, supra note 51, at 716 (describing a “three-prong rights critique . . . that U.S. constitutional rights politically insulate and valorize subordination, legitimate and thus perpetuate greater injustices than they address, and socially alienate us from community”). 56. Critical Perspectives on Rights, BRIDGE, http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/bridge/CriticalTheory /rights.htm (last visited Jan. 27, 2013). 57. Robert Gordon, Some Critical Theories of Law and Their Critics, in THE POLITICS OF LAW 641, 655 (David Kairys ed., 3d ed. 1998). 58. ROBIN WEST, NORMATIVE JURISPRUDENCE: AN INTRODUCTION 126 (2011). 55. 2188 poor people lose Rights are indeterminate because they are too abstract to be useful in deciding particular cases, or because they conflict with other rights. When social progress occurs after a right is declared, it is because of the social and political context in which the right is declared rather than the right itself. Most critiques also claim that rights are regressive. Winning a “right” in a court case either has no connection to advancing a political goal, or actually impedes political goals.59 Gary Peller, for example, faults rights discourse for constituting “a narrative of legitimation, a language for concluding that particular social practices are fair because they are objective and unbiased.”60 Rights impede progressive change because they divert attention and resources away from material deprivations, and, according to some theorists, because rights are individual, rather than about the welfare of groups.61 Some critical race theorists “acknowledg[e] and affirm[ ] . . . that rights may be unstable and indeterminate” but still provide a limited defense of them.62 Patricia Williams, for example, maintains that “rights rhetoric has been and continues to be an effective form of discourse for blacks.”63 In this view rights build solidarity among rights holders,64 give voice to the previously voiceless,65 and stigmatize subordination.66 Likewise, Kimberlé Crenshaw is persuaded that “there simply is no self-evident interpretation of civil rights inherent in the terms themselves,”67 but she finds the critique of rights “incomplete” because it fails “to appreciate fully the transformative significance of the civil rights movement in mobilizing Black Americans and generating new demands.”68 63. Tushnet, supra note 2, at 23. Gary Peller, Race Consciousness, 1990 DUKE L.J. 758, 775. See generally Alan David Freeman, Legitimizing Racial Discrimination Through Antidiscrimination Law: A Critical Review of Supreme Court Doctrine, 62 MINN. L. REV. 1049 (1978). See MARK KELMAN, A GUIDE TO CRITICAL LEGAL STUDIES 275-76 (1990). Patricia J. Williams, Alchemical Notes: Reconstructing Ideals from Deconstructed Rights, 22 HARV. C.R.-C.L. L. REV. 401, 409 (1987) (footnote omitted). Id. at 410. 64. Id. at 414. 59. 60. 61. 62. 65. Id. at 425-26. 66. See Richard Delgado, The Ethereal Scholar: Does Critical Legal Studies Have What Minorities Want?, 22 HARV. C.R.-C.L. L. REV. 301, 305 (1987) (“Rights do, at times, give pause to those who would otherwise oppress us.”). 67. Crenshaw, Race, Reform, and Retrenchment, supra note 16, at 1344. 68. Id. at 1356. 2189 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 iii. the critique of rights, applied to gideon A law review article called The Right to Counsel in Criminal Cases, A National Crisis begins with a series of stories in which criminal defendants were either denied lawyers or had bad lawyers.69 This part of the article is titled “How Can This Be Happening?”70 The critique of rights explains how. Using the five elements just described, this Part attempts to demonstrate that Gideon exemplifies the reasons for skepticism elucidated by the critique of rights. A. The Liberal Overinvestment in Rights Gideon was decided during the 1960s, a period during which, according to Mark Tushnet, the Supreme Court took a “brief, perhaps aberrational, and sometimes overstated role . . . in advancing progressive goals.”71 Perhaps that was why it seemed, at the time, like a victory for the poor and minorities. Gideon was one of those classic Warren Court opinions that provided hope not just about criminal justice, but about economic and racial justice as well.72 That hope is long gone. If Gideon was supposed to make the criminal justice system fairer for poor people and minorities, it has been a spectacular failure. The National Right to Counsel Committee, a panel that was created in 2004 to conduct a comprehensive survey of the state of indigent defense, reported: The right to counsel is now accepted as a fundamental precept of American justice. . . . Yet, today, in criminal and juvenile proceedings in state courts, sometimes counsel is not provided at all, and it often is supplied in ways that make a mockery of the great promise of the Backus & Marcus, supra note 20, at 1031. 70. Id. at 1031. 71. Tushnet, supra note 2, at 34. 69. 72. See Dan M. Kahan & Tracey L. Meares, Foreword: The Coming Crisis of Criminal Procedure, 86 GEO. L.J. 1153, 1153 (1998) (“Law enforcement was a key instrument of racial repression, in both the North and the South, before the 1960’s civil rights revolution. Modern criminal procedure reflects the Supreme Court’s admirable contribution to eradicating this incidence of American apartheid.”); cf. Michael J. Klarman, The Racial Origins of Modern Criminal Procedure, 99 MICH. L. REV. 48 (2000) (describing the process by which egregious civil rights violations motivated by race have historically led the Supreme Court to refine constitutional criminal procedure). 2190 poor people lose Gideon decision and the Supreme Court’s soaring rhetoric.73 Nancy Leong notes that Gideon has been “widely and accurately hailed as a milestone in protecting the rights of individual defendants.”74 This assertion is correct, as far as it goes. Gideon did protect the “rights” of defendants; it turns out, however, that protecting defendants’ rights is quite different from protecting defendants. Fifty years after Gideon, poor people have both the right to counsel and the most massive level of incarceration in the world.75 As stated earlier in this Essay, since Gideon, rates of incarceration (which, in the United States, applies mainly to the poor) and racial disparities have multiplied.76 The right to have a lawyer, at trial or even during the plea bargaining stage, has little impact on either of those central problems. What poor people, and black people, need from criminal justice is to be stopped less, arrested less, prosecuted less, incarcerated less. Considering other needs that poor people have—food and shelter—Mark Tushnet has stated, “[D]emanding that those needs be satisfied—whether or not satisfying them can today persuasively be characterized as enforcing a right—strikes me as more likely to succeed than claiming that existing rights to food and shelter must be enforced.”77 On its face, the grant that Gideon provides poor people seems more than symbolic: it requires states to pay for poor people to have lawyers. But the implementation of Gideon suggests that the difference between symbolic and material rights might be more apparent than real. Indigent defense has been grossly underfunded, where it is provided at all. Moreover, even if the defender community were victorious in getting what it wanted out of Gideon—and the experience of the last fifty years suggests that it will not be—American criminal justice would still overpunish black and poor people. That is the unfairness that the liberal investment in Gideon was supposed to contravene. A lawyer is supposed to be a means to an end, not an end in herself. One problem with Gideon is that it makes the lawyer the end. Robert Gordon noted that “[f]ormal rights without practical enforceable content are easily substituted for real NAT’L RIGHT TO COUNSEL COMM., supra note 49, at 2. Nancy Leong, Gideon’s Law-Protective Function, 122 YALE L.J. 2460, 2462. 75. See Gopnik, supra note 18 (stating that “[n]o other country even approaches” the U.S. incarceration rate). 76. See supra notes 9-10 and accompanying text. 77. Tushnet, supra note 50, at 1394. 73. 74. 2191 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 benefits.”78 In this sense Gideon and poor criminal defendants are friends without benefits. B. The Indeterminacy of Rights On every anniversary of Gideon, liberals bemoan the state of indigent defense. At its core, their claim is that Gideon has not been sufficiently enforced. Indeed, many people would agree that the right to counsel has been violated in cases where defense counsel slept during portions of the trial, where counsel used heroin and cocaine throughout the trial, where counsel allowed his client to wear the same sweatshirt and shoes in court that the perpetrator was alleged to have worn on the day of the crime, where counsel stated prior to trial that he was not prepared on the law or the facts of the case, and where counsel appointed in a capital case could not name a single Supreme Court decision on the death penalty.79 As a practical matter, however, the right to counsel means whatever five or more members of the Supreme Court say it does (or what the social understanding of the right is80). In those cases, the Court found that the Sixth Amendment was not abridged.81 I was part of a team of lawyers that litigated a right-to-counsel case in Georgia. We alleged that, in capital cases, one county appointed counsel on the basis of a low-bidding system. The attorney who agreed to take the case for the least amount of money was the attorney that was appointed, without regard to her competency to represent a defendant in a death penalty case. The trial judge rejected our Sixth Amendment claim. I think we were right, and the trial judge was wrong. I understand, however, that there is no way of applying the Sixth Amendment’s words “in every prosecution, the accused shall enjoy the 78. Gordon, supra note 57, at 657. COLE, supra note 42, at 78-79 (footnotes omitted). 80. Though rights are analytically indeterminate, they may be culturally determined. For example, a “colored only” sign on a public schoolhouse door could be said to be unconstitutional, based on a cultural consensus about the Fourteenth Amendment, even if that understanding doesn’t necessarily follow from the text of the Amendment, and even if the Supreme Court were to declare legally segregated public schools to be constitutional. 81. COLE, supra note 42, at 78-79. 79. 2192 poor people lose right . . . to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence”82 to those facts and obtaining an answer that is objectively right or wrong. On one level the Gideon right is not abstract at all. It has a clear formal content: a person cannot be sentenced to prison unless she is represented by someone who is a member of the bar (or she waives this right). The problem is that the right can be respected without accomplishing anything, as in the above-described cases. In order to make the formal right meaningful, it must be supplemented by some sort of standard-like provisions. But doing so introduces a high level of abstraction that does not decide actual cases. For example, a New York Times article about the Frye and Lafler decisions that extended Gideon to the plea bargaining stage of the criminal process noted that “legal scholars . . . used words like ‘huge’ and ‘bold’ to describe” the decisions and quoted one legal scholar as saying, “I can’t think of another decision that’s had any bigger impact than these two are going to have over the next few years.”83 But the article goes on to state that “legal experts seem to agree . . . that it was difficult to gauge what concrete effect the rulings would have on everyday legal practice.”84 The Times quotes another legal scholar as predicting that the cases would lead to a “flurry” of court filings, “but [that] very few of them will succeed. . . . Courts are very good at tossing these cases out.”85 Under one formulation, the critique of rights means that “rights cannot provide answers to real cases because they are cast at high levels of abstraction without clear application to particular problems.”86 In this light, the first recommendation of the National Right to Counsel Committee—that “[s]tates should adhere to their obligation to guarantee fair criminal and juvenile proceedings in compliance with constitutional requirements”—seems naïve.87 Most states would say they are already in compliance with the Constitution. Yet commissions and panels in Georgia, Virginia, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania have opined that these states are not in compliance with Gideon.88 Even the 82. 83. 84. 85. 86. 87. 88. U.S. CONST. amend. VI. Erica Goode, Stronger Hand for Judges in the ‘Bazaar’ of Plea Deals, N.Y. TIMES, Mar. 22, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/23/us/stronger-hand-for-judges-after-rulings-on -plea-deals.html (quoting Professor Ronald F. Wright). Id. Id. (quoting Professor Stephanos Bibas). Critical Perspectives on Rights, supra note 56. NAT’L RIGHT TO COUNSEL COMM., supra note 49, at 183. Backus & Marcus, supra note 20, at 1035-36. 2193 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 U.S. Department of Justice has acknowledged that “indigent defense in the United States today is in a chronic state of crisis.”89 All of this sets up an extended, and furious, battle about what Gideon requires. The indigent defense community and the Supreme Court will agree sometimes, as in Frye and Lafler, and disagree other times, as in Pennsylvania v. Finley,90 where the Court held that a defendant has no right to counsel in habeas corpus proceedings, and Gagnon v. Scarpelli,91 where the Court held that a defendant has no absolute right to counsel at parole or probation revocation proceedings. Ultimately there are no “right” or “wrong” answers—an answer is “right” if it persuades a court. The vagaries of the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the quality of lawyering that poor people are entitled to seem a risky foundation on which to position a social justice movement. C. Rights Discourse and Mystification American criminal justice is brutal, which is why the United States has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. This is what “law” does. The law allows the police to forcibly stop someone for running away from them in a high-crime neighborhood, even if the police have no other reason to suspect them of a crime.92 The law allows life imprisonment for a first-time drug offense.93 The law allows prosecutors to threaten someone with a life sentence for a minor crime unless he pleads guilty.94 Yet we celebrate Gideon as the “law.” That makes the law seem much more benign than it really is. Gideon’s announcement of a right to counsel appeared to give the poor an agency in criminal justice that they actually do not have. And its brutality would remain visited mainly on the poor. As Richard Delgado observed in 1985, when the prison population was less than half the size it is now: [O]f more than one million offenders entangled in the correctional system, the vast majority are members of the poorest class. Unless we 89. 90. 91. 92. 93. 94. OFFICE OF JUSTICE PROGRAMS & BUREAU OF JUSTICE ASSISTANCE, IMPROVING CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS THROUGH EXPANDED STRATEGIES AND INNOVATIVE COLLABORATIONS, at ix (1999). 481 U.S. 551 (1987). 411 U.S. 778 (1973). Illinois v. Wardlow, 528 U.S. 119 (2000). Harmelin v. Michigan, 501 U.S. 957 (1991). Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 U.S. 357 (1978). 2194 poor people lose are prepared to argue that offenders are poor because they are criminal, we should be open to the possibility that many turn to crime because of their poverty—that poverty is, for many, a determinant of criminal behavior.95 Imagine that many people charged with crimes are legally guilty, i.e., even if these defendants have excellent defense counsel, the prosecution still can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they did what they are charged with doing. Gideon encourages us to think of this state of affairs as “fair.” Consistent with Peter Gabel’s and Jay Feinman’s description of contract law, Gideon “mask[s] the extent to which the social order makes it difficult to achieve true autonomy and solidarity” and “denies the oppressive nature of the existing hierarchies.”96 The progressive investment in Gideon and the movement building around the case makes it seem as though the “poverty and crime” conversation is about the right to a lawyer in a criminal case, and not about the kind of conduct that gets defined as crime, the racialized exercise of police discretion, or why punishment is the state’s central intervention for AfricanAmerican men. D. Isolated Individualism Gideon is a narrative about individual rights rather than a plea for classbased or race-based relief. This is consistent with Wendy Brown’s observation that “rights discourse . . . . converts social problems into matters of individualized, dehistoricized injury and entitlement.”97 The Gideon narrative even comes with a creation myth—Gideon’s Trumpet, the book and movie98— that focuses on the plucky Clarence Earl Gideon, who wrote his petition for cert on prison stationery, and once the Supreme Court awarded him his free lawyer, won his case with the jury deliberating for less than an hour! Mark Tushnet describes the “broad version” of the critique of rights as requiring the “undermining [of] the individualism that vindicating legal rights Delgado, supra note 33, at 10 (footnote omitted). 96. Peter Gabel & Jay Feinman, Contract Law as Ideology, in THE POLITICS OF LAW, supra note 57, at 497, 498. 97. WENDY BROWN, STATES OF INJURY: POWER AND FREEDOM IN LATE MODERNITY 124 (1995). 98. ANTHONY LEWIS, GIDEON’S TRUMPET (1964); GIDEON’S TRUMPET (Hallmark Hall of Fame Productions 1980). 95. 2195 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 reinforces.”99 Gideon instructs us that we should respond to the problem that eighty percent of people charged with crimes in the U.S. are poor by trying to get a lawyer for a poor person charged with a crime.100 This will not solve the problem. Then, of all the actors in the criminal justice system against whom defendants might have a gripe, Gideon tells us it should be against the lawyers who represent them.101 Gideon diffuses solidarity among the 2.3 million people in the United States who are incarcerated. It changes the subject from mass incarceration and racial subordination to private entitlement. E. Rights Discourse as an Impediment to Progressive Social Movements Gideon diverts attention from economic and racial critiques of the criminal justice system. For example, this Essay appears in a Symposium issue of The Yale Law Journal that observes the fiftieth anniversary of Gideon. The Yale Law Journal has not devoted an entire issue to mass incarceration or racial disparities in criminal justice. To the extent that some essays in the symposium make racial critiques of American criminal justice, their authors, like me, must situate those critiques within a discussion of Gideon and explain why the critiques are still salient in light of Gideon.102 I do not think those tasks are difficult, as this Essay hopefully demonstrates, but they do take time and attention from the main problems—mass incarceration and racial disparities. To the extent that scholarship makes any difference, the poor would be better served by my learned coauthors and our able student editors focused explicitly on ending those problems, as opposed to devoting hundreds of pages and work hours analyzing why Gideon has not worked, or how it might work better. It’s rather like a conference of esteemed scientists convening to discuss why holy water does not cure cancer. Something interesting might come out of it, but Tushnet, supra note 2, at 27. 100. See supra note 20. 101. U.S. District Judge Jed Rakoff makes a related point about the Supreme Court’s decisions in Frye and Lafler. He notes that “most of the unfairness that occurs during the plea-bargaining process is, in my experience, not the result of defense counsel’s ineffectiveness. Instead, it is the result of overconfidence on the part of the prosecutors . . . .” Jed. S. Rakoff, Frye and Lafler: Bearers of Mixed Messages, 122 YALE L.J. ONLINE 25, 26 (2012), http://yalelawjournal.org/2012/06/18/rakoff.html. 102. See, e.g., Gabriel J. Chin, Race and the Disappointing Right to Counsel, 122 YALE L.J. 2236 (2013); David Patton, Federal Public Defense in An Age of Inquisition, 122 YALE L.J. 2578 (2013). 99. 2196 poor people lose the public interest might be more efficiently served by focusing on an actual cure. In addition to its diversion function, Gideon also provides a legitimation of the status quo. As discussed in Part I, the poor—especially the poor and black—are incarcerated at exponentially greater levels now than when Gideon was decided. If more poor people are represented by lawyers because of Gideon, arguably their trials or plea bargains are fairer than before Gideon, when they did not have lawyers. Thus, the poor have simultaneously received a fairer process and more punishment. Gideon makes it more work—and thus more difficult—to make economic and racial critiques of criminal justice. This is not to say people cannot and do not make those claims, but rather that Gideon makes their arguments less persuasive. It creates a formal equality between the rich and the poor because now they both have lawyers. The vast overrepresentation of the poor in America’s prisons appears more like a narrative about personal responsibility than an indictment of criminal justice. In the words of one commentator, “Procedural fairness not only produces faith in the outcome of individual trials; it reinforces faith in the legal system as a whole.”103 If prosecutors had brought most of their cases against the poor during the pre-Gideon era when most indigent defendants did not have lawyers, prosecutors would have looked like bullies. Since Gideon, the percentage of prosecutions against the poor has increased from 43% to 80%.104 American prosecutors have so much discretion, and there are so many criminal laws, that they can bring a case against virtually whomever they choose.105 Prosecutors Michael O’Donnell, Crime and Punishment: On William Stuntz, NATION, Jan. 10, 2012, http://www.thenation.com/article/165569/crime-and-punishment-william-stuntz. 104. See Stuntz, supra note 17, at 7 n.7. 105. See Morrison v. Olson, 487 U.S. 654, 728 (1988) (Scalia, J., dissenting) (“With the law books filled with a great assortment of crimes, a prosecutor stands a fair chance of finding at least a technical violation of some act on the part of almost anyone. In such a case, it is not a question of discovering the commission of a crime and then looking for the man who has committed it, it is a question of picking the man and then searching the law books, or putting investigators to work, to pin some offense on him. It is in this realm—in which the prosecutor picks some person whom he dislikes or desires to embarrass, or selects some group of unpopular persons and then looks for an offense, that the greatest danger of abuse of prosecuting power lies. It is here that law enforcement becomes personal, and the real crime becomes that of being unpopular with the predominant or governing group . . . .” (quoting Attorney General [and future Supreme Court Justice] Robert H. Jackson, The Federal Prosecutor, Address at the Second Annual Conference of United States Attorneys (Apr. 1, 1940), in 31 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 3, 5 (1940))). 103. 2197 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 have mostly chosen the poor, but now, because of Gideon, they look like less like bullies. The critique of rights posits that “rights discourse contributes to passivity, alienation, and a sense of inevitability about the way things are.”106 Gideon encourages the view that fairness for poor people is an issue of criminal procedure, not criminal law.107 When it establishes a procedural right, and the poor and racial minorities still complain, mass incarceration and racial disparities start to seem inevitable. When the problem is lack of a right, one keeps going to court until a court declares the right. When the problem is material deprivation suffered on the basis of race and class, where, exactly, does one go for the fix? The Conclusion of this Essay recommends some places. In applying the critique of rights to Gideon, I do not want to discount the important concerns raised by some critical race theorists. The critical race response to the critique of rights exhibits a discordant duality about rights that in some ways accords with this Essay’s analysis of Gideon. As described in Part II, critical race theorists posit that rights are unstable and incoherent but still might be good for people of color. This Essay suggests that Gideon is profoundly limited and limiting, and yet a force for certain sources of good (for example, Gideon authorizes the office of the public defender in Philadelphia that, compared to appointed counsel, gets shorter sentences for its clients108). Even more significantly, Gideon may save the lives of defendants in capital cases, who, occasionally, get better lawyers than they would in a world without Gideon. iv. other comments on rights discourse in criminal procedure Other scholars have also noted the limits of criminal procedural rights to establish racial or social justice. I note three influential analyses of criminal procedure that accord in some ways with this Essay’s application of the critique of rights to Gideon (and in other ways diverge). Professors Louis Michael Seidman, Michael Klarman, and William Stuntz have each observed the failure 106. Critical Perspectives on Rights, supra note 56. Stuntz, supra note 17, at 72 (“Why has constitutional law focused so heavily on criminal procedure, and why has it so strenuously avoided anything to do with substantive criminal law . . . ?”). 108. See Anderson & Heaton, supra note 43. 107. 2198 poor people lose of criminal rights discourse, in specific contexts, to improve fairness in criminal justice. In Brown and Miranda,109 Professor Seidman examined the meaning of two of the most famous Supreme Court decisions: Brown v. Board of Education110 and Miranda v. Arizona.111 Seidman argues that, contrary to conventional understanding, “the decisions did not mandate a vast restructuring of power relationships. Rather, the decisions have served to justify and legitimate arrangements that would otherwise be severely threatened by constitutional rhetoric.”112 He believes that both decisions “served to stabilize and legitimate the status quo by creating the illusion of closure and cohesion.”113 For Miranda, specifically, Seidman posits that there is “a good deal of evidence that Miranda, like Brown, traded the promise of substantial reform implicit in prior doctrine for a political symbol.”114 He acknowledges “some truth”115 to the claim that the decision, which requires that the police advise suspects in custody of their privilege against self-incrimination, empowers individuals who are subject to police questioning. But Seidman notes that the Court had, in a series of cases decided prior to Miranda, already held that the people subject to interrogation while in custody had the right to counsel.116 Miranda’s real purpose was to articulate a mechanism for waiver of the right.117 Citing data that suggests that Miranda did not decrease the number of defendants who confess, Seidman questions whether, for criminal suspects, “Miranda is serving any useful purpose.”118 While Seidman does not explicitly invoke the critique of rights, his analysis is consistent with its view that rights discourse does not necessarily lead to social change, and that it may impede social justice. In Miranda, he states, “the Court tamed the contradictions that would otherwise continually threaten the Louis Michael Seidman, Brown and Miranda, 80 CALIF. L. REV. 673 (1992). 347 U.S. 483 (1954). 111. 384 U.S. 436 (1966). 112. Seidman, supra note 109, at 680. 109. 110. 113. Id. at 719. 114. Id. at 746. Id. at 743. 116. Id. at 744 (“Escobedo, Massiah, and Culombe had already created all the rights any defendant needed.”). 117. Id. 118. Id. at 744 & n.236. 115. 2199 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 legitimacy of punishment in a liberal democracy.”119 He adds that Brown and Miranda created a world where we need no longer be concerned about inequality because the races are now definitionally equal and a world where we need no longer be concerned about official coercion because defendants have definitionally consented to their treatment. . . . Brown and Miranda let us blame the victim in a way we never could under the old regime.120 The two decisions diffuse the dissent that might be expected by the existence of a permanent racially defined underclass because they provide an “amusementpark version of social change.”121 In The Racial Origins of Modern Criminal Procedure,122 Professor Michael Klarman links the development of constitutional criminal procedure to an effort by the Supreme Court to advance racial justice in the South in the era before World War II. He examines four landmark cases in which the Supreme Court held that convictions obtained in mob-dominated trials violated the Fourteenth Amendment right to due process of law, established a right to counsel in capital cases, invalidated a conviction because blacks had been intentionally excluded from the jury, and declared that the right to due process made confessions based on torture inadmissible.123 According to Klarman, “none of these rulings had a very significant direct impact on Jim Crow justice. For example, few blacks sat on southern juries as a result of Norris v. Alabama, and black defendants continued to be tortured into confessing, notwithstanding Brown v. Mississippi.”124 Klarman diverges from the critique of rights, however, in his hopeful analysis of the indirect effects of the cases. He advances the possibility that these cases were “more important for their intangible effects: convincing blacks that the racial status quo was not impervious to change; educating them about their rights providing a rallying 119. Id. at 747. 120. Id. at 752. 121. Id. at 753. Klarman, supra note 72. 123. Id. at 50. The cases are Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86 (1923), which forbade mob trials; Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932), which required the provision of counsel in capital cases; Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935), which reversed the verdict of an intentionally racially exclusive jury; and Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278 (1936), which made confessions obtained by torture inadmissible. 124. Klarman, supra note 72, at 49. 122. 2200 poor people lose point around which to organize a protest movement; and perhaps even instructing oblivious whites as to the egregious nature of Jim Crow conditions.”125 Finally, Professor William Stuntz noticed certain “perverse”126 effects of criminal procedure: as rights have expanded, things have gotten worse for accused persons. Specifically, “underfunding, overcriminalization, and oversentencing have increased as criminal procedure has expanded.”127 The problem is that actors in the criminal justice system can respond to judicial declarations of rights “in ways other than obeying them.”128 States reacted to Warren Court criminal procedure holdings by making the substantive criminal law more punitive, to compensate for the rights provided to accused persons. The result was that criminal cases were focused on procedure. Stuntz believes that this caused American criminal justice to “unravel.”129 Rather than focus on procedural rights, the Warren Court should have used “the federal Bill of Rights . . . to advance some coherent vision of fair and equal criminal justice.”130 Stuntz’s critique is not so much a critique of rights as a critique of the Court’s reliance on procedural rights specifically. 131 One lesson we might garner from these three commentators is that procedural rights may be especially prone to legitimate the status quo, because “fair” process masks unjust substantive outcomes and makes those outcomes seem more legitimate. In contrast, a right to a minimum wage, while it may legitimate unequal distribution of wealth, substantively improves the condition of the least well-off in material ways. conclusion: critical tactics According to David Cole, “the most troubling lesson of the more than 125. Id. at 88. Stuntz, supra note 17, at 3. 127. Id. 126. 128. Id. STUNTZ, supra note 31, at 1. 130. Id. at 227-28. 131. But see Robert Weisberg, Crime and Law: An American Tragedy, 125 HARV. L. REV. 1425, 144243 (2012) (reviewing STUNTZ, supra note 31) (noting that “the Critical Legal Studies movement . . . could have embraced Stuntz’s rights critique as a diagnosis of a brilliant false consciousness-raising mechanism of legitimation in the service of hierarchy”). 129. 2201 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 thirty-five years since Gideon v. Wainwright is that neither the Supreme Court nor the public appears to have any interest in making the constitutional right announced in Gideon a reality.”132 This should not have come as a surprise. The real surprise is the continued investment in rights discourse. Duncan Kennedy observes that “critique is always motivated.”133 My motivation in applying the critique of rights to Gideon is to cause people who want to reform, or transform, American criminal justice to recalibrate their methods. First, I want to be especially clear on one point. People should still become criminal defense attorneys. The most important good that defense attorneys do is helping individual clients. Reducing potential sentences by six months, as one study suggests that effective defense counsel can, makes an enormous difference in the lives of incarcerated people and their families.134 Effective defense attorneys can also increase the cost of prosecution, and, in theory, this has the potential to reduce mass incarceration on a macro level. Excellent defense attorneys might disrupt one or more steps of the five-step process described in Part II by which the criminal law establishes control over poor people. For example, disproportionate stops and arrests of poor African Americans might be inhibited by aggressive litigation. Thus, defense attorneys should continue to fight for the resources that they need to effectively represent their clients.135 But everyone should understand, first, that those resources are not likely to result from raising Gideon-based claims in court, and second, that Gideon has not, and will not, change the fact that in American criminal justice, poor people are losers. The idea of abandoning rights discourse is not as radical as it sounds; rather, it is consistent with the disillusionment, especially on the Left, about the value of going to courts to resolve claims of racial or economic injustice. Professors Cummings and Eagly have described “a new orthodoxy that is deeply skeptical of the usefulness of legal strategies to promote social change.”136 132. COLE, supra note 42, at 64. Kennedy, supra note 50, at 218. See Abrams & Yoon, supra note 44, at 166-67. 135. Abbe Smith, Defense Lawyering in a Time of Mass Incarceration, 70 WASH. & LEE L. REV. 1363 (2013). 136. Scott L. Cummings & Ingrid V. Eagly, After Public Interest Law, 100 NW. U. L. REV. 1251, 1255 (2006) (reviewing JENNIFER GORDON, SUBURBAN SWEATSHOPS: THE FIGHT FOR IMMIGRANT RIGHTS (2005)). 133. 134. 2202 poor people lose So what should people do? I am less certain about what methods will transform criminal justice than I am certain that Gideon discourse will not. I do not view that uncertainty as a flaw in my thesis.137 If people believe that holy water cures cancer, it is a contribution to demonstrate that it does not, even if one does not himself have an actual cure to offer. Thus, rather than profess absolute remedies to mass incarceration and racial disparities, I can offer a few tentative suggestions on how criminal reformers can, in hip-hop parlance, “act like they know” that rights discourse does not work.138 Mark Tushnet notes that proceeding with an awareness of the critique of rights allows progressives “to improve the accuracy of the calculation of the possible benefit of investing in legal action rather than in something else— street demonstrations, public opinion campaigns, or whatever.”139 In the criminal justice context, the goal is to prevent poor people and African Americans from being losers in criminal justice, or at least from losing as badly as they do now. Advocates for the poor, for racial minorities, and for criminal defendants should abandon rights discourse and rather focus on reducing the number of poor people overall, and African Americans specifically, who are incarcerated. The two apparatuses that bear the most responsibility for the massive increase in incarceration and racial disparities since Gideon are the “war on drugs” and the “tough-on-crime” movement. Legalizing or decriminalizing drugs would do some work toward reducing both incarceration overall, and the racial disparities (or, for the latter, at least bring them closer to the two-to-one disparity that existed before the war on drugs, as opposed to the seven-to-one disparity that now exists).140 The 2.3 million people who are locked up in the United States, and their families and friends, have the potential to form a huge social movement against mass incarceration. The critique of rights suggests that historians or political 137. See Allegra M. McLeod, Confronting Criminal Law’s Violence: The Possibilities of Unfinished Alternatives, 8 UNBOUND: HARV. J. LEGAL LEFT (forthcoming 2013) (calling for “an openness to unfinished alternatives—a willingness to engage in partial, in process, incomplete reformist efforts that seek to displace conventional criminal law administration as a primary mechanism for social order maintenance”). 138. The Urban Dictionary defines “act like you know” as “recognize, stop playing, or stop playing crazy.” Act Like You Know, URBAN DICTIONARY, http://www.urbandictionary .com/define.php?term=Act%20like%20you%20know (last visited Mar. 29, 2013). 139. Tushnet, supra note 2, at 25. 140. See supra notes 27-28 and accompanying text. 2203 the yale law journal 122:2176 2013 scientists are better consultants than lawyers in fashioning the best methods for achieving this goal. One animating question might be: What was responsible for social justice advances, like emancipation, that resulted in material gains for African Americans and the poor? Michelle Alexander has proposed that as many criminal defendants as possible go to trial in an effort to “crash the justice system.”141 The idea is to create chaos in the criminal justice system to make ending mass incarceration a priority for politicians and to force a public conversation about it. In other work I have recommended jury nullification as a way of reducing the number of people who are incarcerated for nonviolent, victimless crime.142 Some efforts are already underway. In New York, there have been public demonstrations and civil disobedience to reduce excessive law enforcement in minority communities, especially the police practice of “stop, question, and frisk.”143 A group called Critical Resistance is one of the leaders of the prison abolition project to reduce the reliance on incarceration.144 All of Us or None is an organization of formerly incarcerated people working to end discrimination against people with conviction histories.145 These efforts provide limited optimism that if criminal justice reformers focus on reducing incarceration rather than increasing rights, the poor can lose less. 141. 142. 143. 144. 145. Michelle Alexander, Editorial, Go to Trial: Crash the Justice System, N.Y. TIMES, Mar. 10, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/11/opinion/sunday/go-to-trial-crash-the-justice -system.html. See PAUL BUTLER, LET’S GET FREE: A HIP-HOP THEORY OF JUSTICE (2009); Paul Butler, Racially Based Jury Nullification: Black Power in the Criminal Justice System, 105 YALE L.J. 677 (1995). See Matthew Deluca & Jose Martinez, NYPD’s Stop and Frisk Tactics Protested in Harlem; Princeton Prof. Cornel West Among Those Arrested, N.Y DAILY NEWS, Oct. 21, 2011, http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nypd-stop-frisk-tactics-protested-harlem-princeton -prof-cornel-west-arrested-article-1.965480. CRITICAL RESISTANCE, http://criticalresistance.org (last visited Apr. 3, 2013). All of Us or None, LEGAL SERVICES FOR PRISONERS WITH CHILDREN, http://www .prisonerswithchildren.org/our-projects/allofus-or-none (last visited Apr. 3, 2013). 2204