The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance

advertisement

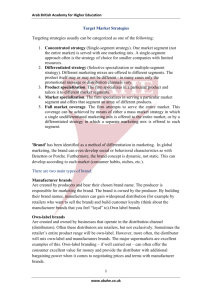

International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance Baolong Ma Beijing Institute of Technology Lin Zhang Truman State University Fei Li Tsinghua University Gao Wang China Europe International Business School The purpose of this paper is to offer a better understanding of the effects of product-harm crisis on a brand’s performance and market structure. This research is based on panel data on milk powder sales during the Nestlé product-harm crisis in China. The NBD-Dirichlet model is used to evaluate the performance of Nestlé and other leading milk powder brands before, during and after the crisis. Our data show that product-harm crises disturb the market structure and change customer behaviour. While a product-harm crisis had a negative effect on Nestlé’s brand performance, it created opportunities for other brands. Overall, our analysis shows that the NBD-Dirichlet model is a valid tool for monitoring the performance changes of both crisis brand and other non-crisis brands during a product-harm crisis. The managerial implications are also discussed. Introduction The term ‘product-harm crisis’ refers to well-known events related to product defects or harm associated with some brands (Siomkos & Kurzbard 1994). For example, in 2000, when news spread that more than 100 people had died in accidents involving defective Firestone tyres, the company had to recall millions of its products (Advertising Age 2000). In September 2008, 6244 babies in China were diagnosed as suffering from numerous ailments after ingesting the poisonous Sanlu formula (People Daily 2008). Having used all of its cash reserves for product recall and Received (in revised form): 26 February 2010 © 2010 The Market Research Society DOI: 10.2501/S1470785309201399 443 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance medical payments, Sanlu Company was declared bankrupt in 2009. In 2005, Nestlé Company mistakenly sold milk powder that contained more iodine than Chinese national standards permit in the market. When the news broke, Nestlé had to make a public apology and remove the defective product from shelves (ABC News 2005). After this crisis, in an effort to restore reduced sales, Nestlé gave out samples and stationed doctors in Beijing supermarkets to deal with customers’ concerns. These examples clearly suggest that a product-harm crisis can seriously imperil a brand’s performance – and even totally destroy a company, as in the case of Sanlu. Therefore, understanding how a product-harm crisis influences brands and the market structure is of great practical and theoretical interest. The NBD-Dirichlet model (Ehrenberg 1988) is a well-established statistical model and has been extensively used to audit and predict brand performance measures (BPMs) under stationary and dynamic market structures (Ehrenberg et al. 2004). However, this model has not been used to analyse the influence of product-harm crises. Since a product-harm crisis can greatly affect brand performance, it is reasonable to assume that, by monitoring the BPMs through the product-harm crisis, we can indirectly observe how a product-harm crisis influences brands and the market structure of this product category. This approach should provide some practical benefits from a new perspective. Our main objective in this paper is to use the NBD-Dirichlet model to monitor the leading brands’ BPMs during the 2005 Nestlé product-harm crisis that occurred in China. By comparing the observed BPMs of the pre-, during and post-crisis periods to those expected, and looking at the differences between these three periods, we may come to understand how a product-harm crisis influences brands (including both crisis brand and non-crisis brands) and market structure. Limitations and managerial implications are discussed. The product-harm crisis and its influence on the brand After a series of product-harm crises over the years, related studies have been developed in a number of research fields. It has been widely accepted that product-harm crises have a negative influence on crisis-brand equity (Heerde et al. 2007). For example, a brand under crisis may lose its baseline sales and become more sensitive to a competitor’s market activities (Heerde et al. 2007). The crisis may also affect the crisis brand’s stock price (Salin & Hooker 2001). Compared to limited systematic research 444 International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4 into crises’ market sequences, past research has focused on consumers’ and firms’ reaction towards such crises (Dawar & Pilluta 2000). Depending on how it is conducted, most research in connection with product-harm crises can be classified into three categories. The first consists of descriptive checklists suggesting which strategies work or do not work in terms of business practices (Mitroff 2004). Because this kind of research cannot quantify the damage incurred, it can only provide limited guidance for understanding the underlying mechanisms of product-harm crises. Another stream of such research focuses on laboratory experiments. Equipped with psychological theories and different control variables, this kind of research can help us understand the moderators that play a part in influencing a product-harm crisis’s effects, and perhaps provides some valuable insights (Dawar & Pilluta 2000; Vassilikopoulou et al. 2009). However, external validity is one limitation of such research. Another research stream has recently grown in popularity, where panel data gathered during real product-harm crises have been collected and analysed using advanced mathematical models (Heerde et al. 2007; Cleeren et al. 2008). How the crisis influences the performance of the crisis brand or the affected product category can be tracked by monitoring the brand’s stock price (Salin & Hooker 2001) or sales (Heerde et al. 2007). By all accounts, this research stream provides more practical insights about the influence of the product-harm crisis. This study contributes to the third research stream in that we used the NBD-Dirichlet model to quantify the product-harm crisis’s effect on BPMs (including penetration, market share, purchase frequency and share of category requirement) and market structure during the 2005 Nestlé milk powder crisis. The NBD-Dirichlet model The NBD-Dirichlet model was developed by Chatfield and Goodhardt (1975), and improved by Ehrenberg (1988). This model is a statistical model based on two well-established assumptions: customers are thought of having steady habitual personal purchase propensities, and brands are characterised with their purchase probabilities and their market shares. In a word, it is based on a stationary market structure. This model has been widely used to describe observed brand performance patterns, and helps to explain and predict them (Kahn et al. 1988; Ehrenberg et al. 2004; Rungie & Goodhardt 2004). With limited numerical inputs, the NBD-Dirichlet model can be used to predict BPMs for particular brands if they are under 445 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance a stationary market (see Table 1 for detailed information). The model and the empirical generalisations associated with them have been widely tested and supported in marketing for over 30 years across European, US, Asian and Australasian markets (Uncles, Ehrenberg & Hammond 1995). Although the NBD-Dirichlet model is based on a stationary market assumption, this does not limit its application only to steady markets (Ehrenberg et al. 2004). For example, the model has been used to audit the performance of established brands (Ehrenberg et al. 2004), as well as niche and ‘change-of-pace’ brands (Kahn et al. 1988). It has been used to predict and evaluate the performance of new brands (Schmittlein et al. 1987; Ehrenberg & Goodhardt 2001), as well as access brands’ performance under price promotion (Ehrenberg et al. 1994) and loyalty programmes (Sharp & Sharp 1997; Meyer-Waarden & Benavent 2006). However, this model has not been applied to product-harm crisis analysis, although past research has shown that it would be a valid tool under such dynamic circumstances. In our research, we used the NBD-Dirichlet methodology to estimate theoretical BPMs, and compared them with those observed measures. Because of the product-harm crisis, we would expect that the market would no longer be stationary. As a result, there would be some discrepancies between the theoretical, or predicted, BPMs and the observed values (Meyer-Waarden & Benavent 2006). These discrepancies may indicate how the crisis ‘disturbed’ the stationary market (Ehrenberg et al. 2004) and affected these brands. Table 1 Brand performance measures Indicators Explanation Market shareThe percentage of the total sales of a given type of product that is attributable to a given company PenetrationThe proportion of the product category customers who buy a special brand at least once in a given period Purchase frequencyThe average purchase rate for those consumers who buy this brand over a special period; this can indicate the customers’ loyalty Share of category requirements (SCR)The brand’s share among the group of consumers who bought the brand at least once during a special period 446 International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4 Data and methodology The Retailing Research Center of Tsinghua University provided the panel data used in this analysis, which includes purchase data on 53 product categories from 336 families in the Beijing area during the period from January 2004 to December 2005. These data recorded the detailed purchase information of each product category (for example, brand name, purchase volume, purchase price, purchase time and purchase locations). Our analysis shows that there were more than 70 milk powder brands in the market during this period. However, for the purposes of this study, we focused only on four leading brands: Yili, Nestlé, Wondersun and Mengniu. The Nestlé milk powder incident began on 25 May 2005 (ABC News 2005), and we can assume that the market before May 2005 was stationary. We first used the 12 months’ data before the crisis (i.e. April 2004–April 2005) to fit the NBD-Dirichlet model, and predict the normal brand performance and market structure. We then focused on data from three distinct three-month periods (pre-crisis – 25 February 2004 to 24 May 2005; during-crisis – 25 May 2005 to 24 August 2005; and post-crisis – 1 October 2005 to 31 December 2005). Theoretical BPMs (penetration, purchase frequency, share of category requirements (SCR), etc.) from each period were estimated using the fitted NBD-Dirichlet model, and these estimated values were then compared to those observed values. This enabled us to detect whether there were deviations due to the productharm crisis. When determining whether the deviations were significant or not, we used the standards from Fader and Schmittlein (1993): +/– 3% for market share, +/– 3% for penetration, +/– 0.3 for purchase frequency, and +/– 3% for SCR. For example, if the theoretical SCR is different from the observed SCR by more than 3%, we determined that the discrepancy is significant. The three-month period was chosen based on the following factors. First, we wanted to set the period as short as possible, so that the companies could quickly track the transitions of BPMs. Besides, it is impractical for companies to wait for a long time before they can make any estimation of the crisis’s influence. Second, according to Ehrenberg et al. (2004), the base analysis period for BPMs should be greater than the average inter-purchase interval. Since our data show that the average inter-purchase interval of milk powder is around 1.3 months, a three-month period should be appropriate. Third, the extensive media coverage on this product-harm crisis extended from 25 May to the end of August 2005. Therefore, we think the period from 25 May 2005 to 24 August 2005 should be one 447 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance when the market was greatly disturbed by the crisis. Fourth, the BPMs are dependent on the period. For example, a brand’s penetration will be much higher in a year than in a week. In contrast, SCR will be lower in a longer period (Ehrenberg et al. 2004). To minimise the error when comparing the BPMs across different periods, we chose the same duration for each period. Results Model fitness and brand performance measures before the crisis Table 2 presents four key brand performance measures based on 12 months’ data before the crisis (i.e. April 2004–April 2005). These theoretical BPMs match very well with the observed values (the correlations between observed and theoretical values are 0.99 for market share, penetration and SCR, 0.92 for purchase frequency). This result shows that this was a stationary market. The observed purchase frequencies and penetrations of four leading brands are represented in Figure 1, where the x-axis marks the penetration while the y-axis indicates the purchase frequency. The estimated values from the NBD-Dirichlet model are also marked in Figure 1. The straight line in the figure connecting the observed values represents a least squares regression line using the observed penetration and purchase frequency. The other line connects the theoretical values. The points in Figure 1 clearly mark the marketing positions of each brand. It is obvious that a small brand has fewer buyers (lower penetration) than larger brands, and its customers tend to buy it less frequently (less purchase frequency); this is the so-called ‘double jeopardy’ phenomenon (Ehrenberg et al. 1990). It is also clear that the variation on the observed penetration and market Table 2 Part BPMs from the 12-month period before the crisis Nestlé Brand Yili Wondersun Mengniu T O T O T O T O Market share (%) 13.45 12.00 13.30 11.83 7.23 7.69 5.41 6.59 0.99 Penetration (%) 23.90 24.86 23.67 24.29 13.70 14.00 10.44 10.29 0.99 1.9 1.61 1.9 1.67 1.78 1.59 1.75 1.48 0.92 38.13 40.61 38.05 35.89 34.99 32.58 34.10 37.04 0.99 Purchase frequency SCR (%) Correlation Notes: T = theoretical value; O = observed value; the correlation is based on all brands in this product category (more than 70 brands). 448 International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4 3.0 2.8 y = 0.009x + 1.419 R2 = 0.717 2.6 2.4 2.2 Purchase frequency 2.0 Mengniu 1.8 Yili Wondersun Nestlé Yili 1.6 1.4 Mengniu Nestlé Wondersun 1.2 1.0 Observed values 0.8 Theoretical values 0.6 Linear regression values 0.4 0.2 0 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 Penetration (%) Figure 1 Double jeopardy in the pre-crisis market share among different brands were greater (for example, the penetration from maximum 24.86 of Nestlé to minimum 10.29 of Mengniu, a ratio of 2.4 to 1), while the purchase frequency and SCR variation were relatively smaller (for example, the observed purchase frequencies are all within the 1.57 +/– 0.1 range). This is consistent with previous findings (Ehrenberg et al. 2004). We also used the NBD-Dirichlet model to analyse the three-month precrisis data. Both the predicted BPMs and the observed BPMs from this period are listed in Table 3. Clearly, there were no significant deviations between theoretical measures and the observed measures, and this shows that the market was stationary. This also indicates that choosing a threemonth period as the basic period is appropriate. Similar to the one-year period data, the market share and penetration differed greatly among four brands, while the purchase frequencies and SCRs had tighter distribution. From observed values during this period, Yili and Nestlé had greater market share than the other two brands. Yili also had the highest purchase frequency and SCR, although some of the margin was not significant. Comparing the BPMs from the one-year period and those from the three-month period, we found that the penetrations of four leading brands 449 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance Table 3 Part BPMs from the pre-, during and post-crisis periods (each period lasts three months) Nestlé Brand Yili T O Before 9.36 9.19 8.13 Market share (%) During 4.34 3.86 10.93 5.74 5.17 Before 11.83 During 7.39 After Before During After Penetration (%) Purchase frequency SCR (%) After T Wondersun O Mengniu T O T O 10.29 8.85 7.35 5.48 5.25 12.63 9.28 7.37 8.12 6.32 8.60 9.59 8.27 6.64 7.68 5.90 12.57 10.33 10.86 11.21 12.00 7.06 7.43 7.62 17.73 18.10 15.23 16.19 13.45 14.29 9.27 9.57 13.62 13.91 13.12 13.91 12.24 13.04 1.72 1.59 1.71 1.96 1.72 1.43 1.69 1.54 1.58 1.38 1.66 1.89 1.64 1.24* 1.62 1.20* 1.46 1.27 1.49 1.63 1.48 1.13* 1.48 1.17* Before 55.80 53.03 55.34 57.33 55.61 55.90 54.38 56.67 During 42.20 32.36* 45.05 62.07* 44.32 45.65 43.81 41.00 After 45.84 41.85* 47.00 59.09* 46.87 49.25 46.63 45.56 Notes: T = theoretical value; O = observed value; * indicates that there is significant difference between the observed and the theoretical indicators. from the one-year period were greater than those from the three-month period. On the other hand, the SCRs from the one-year period were smaller than those from the three-month period. This is consistent with previous findings (Ehrenberg et al. 2004). Brand performance measures during the crisis To check how much the brands were affected by the product-harm crisis, we also used the model to analyse the during-crisis period data. Both the predicted BPMs and the observed BPMs are listed in Table 3. Obviously, there were significant deviations between the predicted measures and the observed measures (see Table 3). For example, the observed SCR of Nestlé was 9.84% less than the theoretical value, while the observed SCR of Yili showed a positive deviation of 17.02%. In addition, the observed purchase frequencies of Mengniu and Wondersun were significantly lower than those predicted values (by 0.4 and 0.42 respectively). It is clear that the Nestlé product-harm crisis disturbed the market and the market was not stationary during this period. 450 International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4 During the crisis, Yili had the highest market share, penetration and SCR, while Nestlé was the lowest among these four brands. Yili also led in terms of purchase frequency, while the other three brands had very close purchase frequencies. Brand performance measures after the crisis During a product-harm crisis, extensive media coverage draws public attention and therefore the crisis has maximum effect on the market structure. However, after a period of time, the media will reduce its coverage of the crisis, the crisis’s influence on the market will decline and the market will probably shift to another stable condition. How the brands perform under this new market structure is of great interest. As one of our efforts to shed light on this question, we used the NBD-Dirichlet model to analyse the three-month post-crisis data. The results are listed in Table 3, which shows that the observed BPMs had some deviations from the expected measures. These deviations are similar to those in the during-crisis period. For example, the observed SCR of Nestlé and Yili showed –3.99% and 12.09% deviation respectively. On the other hand, the observed purchase frequencies of Mengniu and Wondersun were 0.31 and 0.35 less than the prediction, respectively. Clearly, four months after the outbreak of Nestlé’s product crisis, the market was still not steady. During this period, Yili maintained the highest market share, while Nestlé had the lowest market share. However, the difference between Nestlé and Wondersun or Mengniu was insignificant. In terms of penetration, Nestlé was still the lowest, but the other three brands were all very close to one another. Yili maintained the highest purchase frequency and SCR, while Nestlé had the lowest SCR. Compare brand performance measures across three different periods To understand how the product affects the brand performance of the leading brands, we put the BPMs of these brands from the three periods (pre-, during and post-crisis) together in Table 3. Because the market was not steady in the during and post-crisis periods, we focused only on the observed BPMs when comparing these brands. In terms of market share, Nestlé experienced significant changes across these three periods: it had 9.19% market share in the pre-crisis market, it dropped to 3.86% during the crisis and recovered to 5.17% in the postcrisis period. This indicates that the product crisis resulted in a market 451 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance share shrink for the crisis brand, and the market share recovered slowly after the product crisis but was still less than the pre-crisis level. At the same time, the other three brands all experienced insignificant changes – that is, they increased from pre-crisis levels to during-crisis levels, and eventually dropped back in the post-crisis period. Examining the penetration of the four brands during these three periods, we found that they all experienced significant changes. For example, following the trend of its market share, Nestlé’s penetration was 12.57% in the pre-crisis period; it dropped to 7.62% during the crisis and recovered to 9.57% in the post-crisis period. On the other hand, the penetration of the other three brands experienced similar transitions, increasing from the pre-crisis period to the during-crisis period, then dropping to an intermediate level (between the pre-crisis and during-crisis periods) in the post-crisis period. One interesting finding is that the purchase frequencies of the four brands dropped from the pre-crisis period to the during-crisis period, and kept dropping into the post-crisis period. Although each step of the changes was insignificant, if we compare the post-crisis level to the pre-crisis level, we find that all four brands displayed a significant or marginally significant drop. Overall, Nestlé did not seem different from the other three brands. The SCRs of these four brands experienced a totally different transition than the other three BPMs. For example, Nestlé, Mengniu and Wondersun all experienced SCR drop from the pre-crisis period to the during-crisis period; and all recovered somehow in the post-crisis period. The only exception is Yili: its SCR increased from 57.33% in the pre-crisis period to 62.07% in the during-crisis period and eventually dropped back to 59.09% in the post-crisis period. To better display the performance transition from the pre-crisis period to the post-crisis period, the penetrations and purchase frequencies of these four brands during these three periods are all plotted in Figure 2. Two things are obvious: first, this crisis harmed Nestlé’s penetration greatly, while the other three brands benefited to some extent from this crisis; second, the purchase frequencies of each brand and even the entire product category fell after this crisis. However, Yili always had the leading purchase frequency while the other three brands’ purchase frequencies were close to one another. 452 International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4 2.2 Nestlé (N) Ybefore Purchase frequency 2.0 Wondersun (W) Yduring 1.8 Mbefore Wbefore 1.4 Nduring Nafter 1.2 1.0 Mafter 7 Mengniu (M) Yafter Nbefore 1.6 Yili (Y) 9 11 Mduring Wduring Wafter 13 15 17 19 Penetration (%) Figure 2 The performance transitions from the pre-crisis period to the post-crisis period Discussion This study focused on the Nestlé milk powder crisis that occurred in China in 2005. Based on panel data from 336 families in the Beijing area, we studied the effects of a product-harm crisis on brands and market structure using the NBD-Dirichlet model. We found, first, that the market structure in the pre-crisis period was stationary. The product-harm crisis disturbed the balance, and the market during the crisis was no longer steady. As a consequence, the predictions of purchase frequencies and SCRs were not consistent with the observed measures. Four months after the outbreak of the crisis, the overall market was still not back to stationary status and there were some deviations of SCRs and purchase frequencies. This indicates that the crisis’s influence on the market still existed, and it might last for some time. However, it is interesting to point out that the observed market share and penetration seemed to match the predicted measures in all three periods. When the market was not steady in the during-crisis and the post-crisis periods, detailed data show that in most situations the observed purchase frequencies (Mengniu and Wondersun) or SCRs (Nestlé) were significantly lower than the estimated measures. This may indicate that Mengniu and Wondersun acquired some new customers from Nestlé, and these new customers did not commit heavy purchases to these brands. (This is explained in more detail in the following paragraph.) Our data also show that, among those non-crisis brands, Yili was an exception, with higher than expected SCR in both the during and post-crisis periods. In addition, the observed purchase frequencies of Yili in the during and 453 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance post-crisis periods were always greater than the predicted measures, even though the difference was less than 0.3. This may relate to its market position: in both periods, Yili had the highest market share, with more than 3% margin, while its penetration was similar to that of its competitors. Second, a product-harm crisis hurts the crisis brand greatly. Our data clearly showed that the market share and penetration of Nestlé dropped significantly during the product crisis. Even though these measures recovered during the post-crisis period, they were still significantly lower than their pre-crisis levels. On the other hand, those non-crisis brands benefited from this crisis with significantly higher penetration, although our data also show a trend of returning to their pre-crisis levels. The decreased market share of Nestlé redistributed to all other brands (more than 70 brands), and each of them took only a part of it. Therefore, no significant change of market share was seen in the non-crisis brands. Third, the crisis’s influence on purchase frequency and SCR of the crisis brand was not significantly different from those of the non-crisis brands. In terms of purchase frequency, this similarity lies in two aspects: in all three periods, Nestlé’s relative purchase frequency was always the same (significantly lower than Yili but marginally higher than the other two brands); and during the transition from the pre-crisis period to the postcrisis period, all four leading brands dropped by around 0.3. Similarly, the observed SCRs of Nestlé, Mengniu and Wondersun all experienced a similar drop from the pre-crisis period to the during-crisis period, and recovered to some extent in the post-crisis period. Previous research shows that new brands garnered customer loyalty immediately after they were introduced (Ehrenberg & Goodhardt 2001). Our data further show that even a product-harm crisis will not hurt the crisis brand’s customer loyalty. Overall, Nestlé’s penetration and market share decreased dramatically, while other brands experienced an increase in penetration at the same time. Associated with this transition, the purchase frequencies and SCRs of most leading brands dropped significantly. Combining these observations, one reasonable explanation can be given. The product-harm crisis drove some of Nestlé’s customers away to other brands. These switched customers did not form stable purchase behaviour – in other words, they did not limit their purchases to any one special brand. These switched customers were somehow like ‘change-of-pace’ customers (Kahn et al. 1988). Even though the non-crisis brands attracted some new customers and increased their market share or penetration, the average loyalty of their new customer group was low. As a result, their purchase frequencies or SCRs became even lower. This combination of higher penetration and lower loyalty is 454 International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4 similar to what happens to change-of-pace brands (Kahn et al. 1988) or to normal brands under deep price cuts (Bhattacharya et al. 1996). Finally, we may need to pay particular attention to Yili. Yili was special in many aspects. First, it always had the highest market share in all three periods. Second, in both the during and post-crisis periods, its observed SCRs were significantly higher than the estimated SCRs. Third, its observed SCR increased from the pre-crisis period to the during-crisis period, while all the other brands experienced SCR drop. Fourth, its observed purchase frequency always led the market with a significant margin. All these may relate to one fact – that Yili was the biggest brand in the pre-crisis market. Our research indicated that, even though all non-crisis brands benefited from Nestlé’s crisis, different brands gained differently; the most dominant brand gained more in terms of market share, even increasing SCR, while the smaller brands had smaller gains in market share and also had to sacrifice SCR. This looks like another ‘double jeopardy’ smaller brands may have to face in reality. Interestingly, according to Heerde et al. (2007), smaller brands are more damaged than bigger brands after a productharm crisis. Our research is consistent with that of Heerde et al. (2007) in supporting that it is always good to be a bigger brand and it is always bad to be a smaller brand. Conclusion To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first attempts to apply the NBD-Dirichlet model to investigate the effects of a productharm crisis. This paper provides a methodology by which to assess the impact of a product crisis in a quantitative way, and applies the model to a product-harm crisis for Nestlé milk powder in the Chinese market. The research shows that this model is a great tool by which to monitor or track the development of a product-harm crisis. The modelling and estimation processes are straightforward, and the required data can easily be collected. Using this model helps us to monitor the crisis’s influence on the crisis brand, non-crisis brands and even the entire category market. Our research shows that a product-harm crisis can greatly damage the crisis brand’s market share and penetration. However, purchase frequency and SCR were not damaged at similar levels. These combined data indicate that the market was not steady, and a product crisis changed customers’ purchase behaviours. More specifically, a product-harm crisis drove away some customers of the crisis brand and these switched customers did not make up their minds about which brand to eventually switch to. The 455 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance periods during and after the crisis were critical to both of the crisis brands and non-crisis brands. For crisis brands, they need to maximise their efforts to attract back this group of customers before they commit to other brands. However, for non-crisis brands, even though they had improved their market share and expanded their customer base, they should realise that this is just a temporary improvement. They need to try their best to keep these new customers satisfied, and eventually make them loyal customers. Their strategies and practices during this period will eventually affect whether they can keep these new customers. Limitations This study has its limitations. First, it used data only from 336 families in the Beijing area, so probably cannot represent the entire population. Future research collecting data from a more representative population might provide greater insights. Second, our data covered just seven months after the outbreak of the crisis, and the market was still not steady. Future research with a longer period of data might provide more detailed information. Third, we focused only on the product category of milk powder, which is characterised by high purchase frequency. Therefore, caution needs to be exercised before the conclusions in our study are applied to other products with lower purchase frequency (cars, for example). References ABC News (2005) Nestlé apologizes for excess iodine in baby milk, 7 June. Available online at http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2005/06/07/1386244.htm. Retrieved on 12 September 2009. Advertising Age (2000) Firestone woes create opportunity, 18 September. Bhattacharya, C.B., Fader, P.S., Lodish, L.M. & DeSarbo, W. (1996) The relationship between the marketing mix and share of category requirements. Marketing Letters, 7, 1, pp. 5–18. Chatfield, C. & Goodhardt, G.J. (1975) Results concerning brand-choice. Journal of Marketing Research, 12, 1, pp. 110–113. Cleeren, K., Dekimpe, M.G. & Helsen, K. (2008) Weathering product-harm crisis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36, 2, pp. 262–270. Dawar, N. & Pilluta, M.M. (2000) Impact of product-harm crisis on brand equity: the moderating role of consumer expectations. Journal of Marketing Research, 37, 2, pp. 215– 226. Ehrenberg, A.S.C. (1988) Repeat Buying, Facts, Theory and Applications. New York: Oxford University Press. Ehrenberg, A.S.C. & Goodhardt, G. (2001) New brands: near-instant loyalty. Journal of Targeting, Measurement & Analysis for Marketing, 10, pp. 9–16. 456 International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4 Ehrenberg, A.S.C., Goodhardt, G.J. & Barwise, P. (1990) Double jeopardy revisited. Journal of Marketing, 54, 3, pp. 82–91. Ehrenberg, A.S.C., Hammond, K. & Goodhardt, G.J. (1994) The after-effects of price-related consumer promotions. Journal of Advertising Research, July/August, pp. 11–21. Ehrenberg, A.S.C., Uncles, M.D. & Goodhardt, G.J. (2004) Understanding brand performance measures: using Dirichlet benchmarks. Journal of Business Research, 57, 12, pp. 1307– 1325. Fader, S.P. & Schmittlein, D.C. (1993) Excess behavioral loyalty for high-share brands: deviations from the Dirichlet model for repeat purchasing. Journal of Marketing Research, 30, 4, pp. 478–493. Heerde, H. Van, Helsen, K. & Dekimpe, M.G. (2007) The impact of a product-harm crisis on marketing effectiveness. Marketing Science, 26, 2, pp. 230–245. Kahn, B., Kalwani, M. & Morrison, D. (1988) Niching versus change-of-pace brands: using purchase frequencies and penetration rates to infer brand positioning. Journal of Marketing Research, 25, 4, pp. 384–390. Meyer-Waarden, L. & Benavent, C. (2006) The impact of loyalty programmes on repeat purchase behaviour. Journal of Marketing Management, 22, 1, pp. 61–88. Mitroff, I. (2004) Crisis Leadership: Planning for the Unthinkable. New York: John Wiley & Sons. People Daily (2008) The number of baby sufferers of milk powder incident reached 6244, among which 158 suffered from acute renal failure, 17 September. Available online at . http://society.people.com.cn/GB/86800/8060739.html. Retrieved on 12 October 2008. Rungie, C. & Goodhardt, G. (2004) Calculation of theoretical brand performance measures from the parameters of the Dirichlet model. Marketing Bulletin, 15, 2, pp. 1–9. Salin, V. & Hooker, N.H. (2001) Stock market reaction to food recalls. Review of Agricultural Economics, 23, Spring/Summer, pp. 33–46. Schmittlein, D.C., Morrison, D.G. & Colombo, R. (1987) Counting your customers: who are they and what will they do next? Management Science, 33, pp. 1–24. Sharp, B. & Sharp, A. (1997) Loyalty programs and their impact on repeat-purchase loyalty patterns. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14, pp. 473–486. Siomkos, G.J. & Kurzbard, G. (1994) The hidden crisis in product-harm crisis management. European Journal of Marketing, 28, 2, pp. 30–41. Uncles, M.D., Ehrenberg, A.S.C. & Hammond, K. (1995) Patterns of behavior: regularities, models, and extensions. Marketing Science, 14, 3, pp. G71–G78. Vassilikopoulou, A., Lepetsos, A., Siomkos, G. & Chatzipanagiotou, K. (2009) The importance of factors influencing product-harm crisis management across different crisis extent levels: a conjoint analysis. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 17, 1, pp. 65–74. About the authors Baolong Ma is Assistant Professor of Marketing at Beijing Institute of Technology and a primary researcher of The Retailing Research Center at Tsinghua University. He works primarily in the areas of customer relationship management, brand management and crisis management and has written numerous scholarly articles on topics in these areas. Lin Zhang is Assistant Professor of Marketing at Truman State University. She completed her Ph.D. in Marketing at Mississippi State 457 The effects of product-harm crisis on brand performance University in 2006. Her research interests include brand management, comparative advertising and unhealthy consumption behaviour. Her research has been published in journals such as Marketing Management Journal and Management Research News and AMA proceedings. Fei Li is Professor of Marketing at Tsinghua University. Gao Wang is Professor of Marketing at China Europe International Business School. Address correspondence to: Lin Zhang, School of Business, Truman State University, Kirksville, MO 63501, US. Email: linzhang@truman.edu 458 Copyright of International Journal of Market Research is the property of World Advertising Research Center Limited and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.