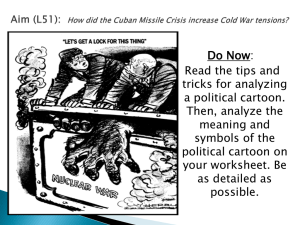

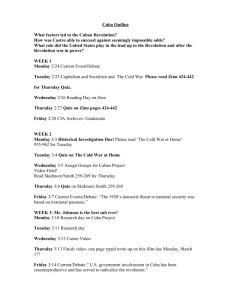

the cuban military and transition dynamics

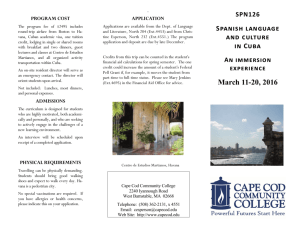

advertisement