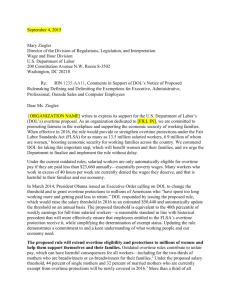

September 4, 2015 Submitted via www.regulations.gov Mary Ziegler

advertisement