The Freedom of the Lame Duck: Presidential Effectiveness In the

advertisement

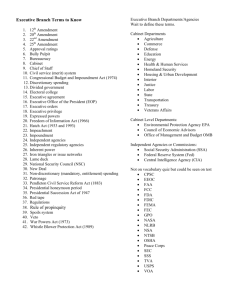

The Freedom of the Lame Duck: Presidential Effectiveness In the Post-Twenty-Second Amendment Era VINCENT A. PACILEO IV University of Connecticut Limiting himself to only two terms as president, George Washington established what would become a long respected tradition. However, in a time of crisis, Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for an unheard of third and fourth term, prompting the Eightieth Congress of the United States to institutionalize a two-term limit on the presidency. The ratification of the Twenty-Second Amendment in 1951 soon popularized the phrase “lame duck” to signify a weakening of presidential power during the second term and following the midterm elections. By way of five indicators of presidential effectiveness, this paper seeks to examine the lame duck presidency in order to determine if presidential power has been negatively impacted since the amendment’s passage. I find that across all indicators, the prevalence of any lame duck phenomenon is purely imagined and therefore advocate repeal of the amendment. “Duration in office…has relation to two objects: to the personal firmness of the executive magistrate in the employment of his constitutional powers and to the stability of the system of administration which may have been adopted under his auspices.” – Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 71 March 18, 1788 “It is a circumstance strongly in favor of rotation...If the office is to be perpetually confined to a few other men of equal talents and virtue, but not possessed of so extensive an influence, may be discouraged from aspiring to it.” – Melancton Smith, Delegate, New York June 15, 1788 Several years after the passage of the Twenty-Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, presidential scholar James MacGregor Burns declared, “Virtually all political scientists and students of American history agree” that “presidential influence” has been significantly weakened by the amendment (Korzi 2007, 4). The academic community accepted this point of view, regardless of its accuracy, for almost two decades, at which time Paul Davis reassessed the 1 implications of the enactment of the Twenty-Second Amendment. Davis found “there appears to be no unanimity of scholarly opinion as to whether the TwentySecond Amendment impeded, helped, or had no effect whatsoever” on the president’s power (Davis 1979, 295). By the turn of the century, scholarship changed yet again: Presidential historian Lewis Gould directly linked second term failures in part to the Twenty-Second Amendment. He suggested, “Most chief executives would have had a better historical reputation had they had contented themselves with a single elected term” (Gould 2003, xv). Gould continued that the amendment drains presidential power and produces the “lame duck phenomenon” during the second term, creating “an environment in which the first term was only seen as a prelude to the productive second term” that would supposedly “validate presidential greatness” (Gould 2003, xv). The significant disagreement over time among scholars regarding the consequences of the Twenty-Second Amendment suggests that further study is needed not only to understand its impact on “lame duck” presidents but also reassess whether the amendment is suitable for our democratic system. LITERATURE REVIEW Little scholarship exists on the subject of lame duck theory, its application to the presidency, or relationship to the Twenty-Second Amendment. However, this may well be the result of the term’s varied use and application. A search of The Merriam Webster Dictionary reveals both a traditional meaning of the term, denoting a person “whose position or term of office will soon end,” as well as a more ambiguous definition: “One that is weak or that falls behind in ability or achievement” (Merriam-Webster). What precisely does this mean? In the context of the presidency, the phrase has been used to describe presidents in their second term of office that face a reduction in power and effectiveness and a waning influence in policy matters. Originally, “lame duck” was a business term used in the eighteenth century “to describe anyone who was bankrupt or behind on their debt payments…By 1910, newspapers began using the phrase in its current incarnation: a reference to an elected official whose term is nearing an end and, freed from the accountability of voters, could be prone to ineffectiveness or acts of self-interest” (Kocieniewski 2006). The term continued to grow in use, particularly following the passage of the Twenty-Second Amendment. This Constitutional incorporation of term limitations on the office of the presidency has given rise to much of the uncertainty and scholarship surrounding the implications of the lame duck presidency. Overall, the political science research concerning lame duck theory has revolved around several themes. Foremost, scholars established methods of identifying the modern lame duck president: First, when presidents announce that they are not planning to run for office again; and second, presidents who may or may not be eligible to run are lame ducks following the mid-term Congressional elections (Neustadt 1990, 197). The latter is especially true if a president’s own 2 party loses ground in the midterm elections and therefore represents one key indicator relevant to this study. Additionally, much of the literature investigates the term “lame duck” and its prevalence in the national media and the presidential transition period. Thematic media analyses of the party overturn type have demonstrated how immediately the news media’s attention shifts from the incumbent president to the president-elect in an attempt to capture the “the sharpest problems of leadership, continuity, and institutional adjustments” that accompany the complexities of presidential transitions (Johnson 1986, 53). The news media largely treat any actions by the incumbent during this period as “the pitiful, last gasps of a dying giant” that attempts to maintain power through “useless acts of desperate political egos” (Johnson 1986, 62). Content analyses of two major newspapers-of-record revealed that certain issues and behaviors of the president set off the media’s use of “lame duck” (Silber 2007, 1). In particular, “Concerns of lame duck status are mentioned [by the media] early in a president’s first term,” which may indicate a lack of confidence in the president from the very beginning (Silber 2007, 8). Scholars also seek to differentiate the presidential transition from the presidential interregnum – the former referring to the policy preparations of the incoming administration and the latter to the policy activities of the outgoing administration (Klotz 1997, 320). This distinction has shed light on the activities of the outgoing president, who is relevant “only to the extent which their activity facilitates or hinders” the transition of power to the president-elect (Klotz 1997, 320). More importantly, an incumbent president will refrain from erratic activities during this time and instead focus on three key areas: “A foreign policy emphasis; action taken in areas that are clearly identified with the administration; and greater success in unilateral activity” (Klotz 1997, 323; Tseng 2003, 2). In all of these areas, actions taken by the president are to sustain what little political capital he has left due to his lame duck status. The dynamics of political time and the advisability of second terms are a final consideration. Political science research has investigated the six-year single term presidency as an alternative to the status quo (Buchanan 1988). Reviewing the scholarship on the subject, David Crockett writes, “History demonstrates that second terms are far more problematic than first terms, afflicted with ‘sixth year itches,’ ‘sixth year curses,’ and the more generic ‘second term blues’” suggesting that perhaps there is some merit to the proposal (Crockett 2007, 708). Qualitatively, a four-year term offers little political time for a president’s agenda. According to one White House aide, “You should subtract one year for the reelection campaign, another six months for the midterms, six months for the start-up, six months for the closing, and another month or two for an occasional vacation. That leaves you with a two-year Presidential term” (Light 1999, 17). 3 THE FRAMERS AND PRESIDENTIAL RE-ELIGIBILITY The Constitutional Convention held in May of 1787 was designed to remedy the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation but ultimately resulted in an entirely new governing document. Two dominant viewpoints emerged during the debates over the Constitution: The Federalists, who claimed George Washington, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton among their ranks, believed a Constitution that supported a strong central government would more closely unite the states as a nation. Maintaining an effective and independent executive was key to that success. The opposing Antifederalists were in favor of limited government, fearing that the Constitution granted the executive too much power (Ketcham 1986, 13). Each argument is considered here in turn, stressing first the Antifederalist argument against re-eligibility and then the corresponding Federalist response. These arguments are critical to this study given that all future debates in Congress concerning the re-eligibility of the president are based solely on concerns raised by Antifederalists, who over time haven been labeled as “men of little faith”1 lacking the visionary confidence of the Federalists (Johnson 2004, 649). In New York State, where ratification was necessary, the Constitution became the target of opponents who wrote dozens of public letters to support their views. By no means an organized effort, the Antifederalists wrote articles pseudonymously, using pen names such as “Cato” and the “Federal Farmer.” Melancton Smith, a prominent New York City lawyer, is widely regarded as the face behind the Federal Farmer, the best known of the Antifederalist pamphlets. A comparison between the writings of the Federal Farmer and Smith’s speeches during the New York ratifying convention stress a central theme of representation and presidential tenure such that “two of Smith's four major speeches at the convention (and several of his shorter comments) dwell on representation as their major theme [much] like the Farmer” (Webking 1987, 515). Smith also believed that unlimited terms for the executive was a threat to republicanism and that an amendment should be attached to the Constitution restricting tenure. “The amendment will have a tendency to defeat any plots against liberty and authority of the state governments,” he said. “I think that a rotation in the government is a very important and truly republican institution. All good republicans, I presume to say, will treat it with respect” (Ketcham 1986, 350). To combat authors such as the Federal Farmer, a more organized and concerted effort was undertaken by three prominent Federalists, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. Together, they wrote eighty-five articles in defense of the Constitution, which were published across New York State under the pseudonym “Publius.” Hamilton first raises the issue of presidential tenure in Federalist No. 71 and elaborates on his argument in No. 72. He writes that there is an intimate connection between the duration of the executive and the ability of the 1 For further reading, see Cecelia Kenyon’s influential essay, Men of Little Faith: The AntiFederalists on the Nature of Representative Government, The William and Mary Quarterly vol. 12, no. 1 (1955): 4-43. 4 system of administration regarding re-eligibility (Hamilton, 435). Duration allows the executive an opportunity to succeed while re-eligibility allows the people to keep a leader in office and secure “the advantage of permanency for government” (Hamilton, 436). Directly addressing the Antifederalist position, Hamilton stresses that limits on the presidency will have several ill effects: Limiting presidential eligibility would diminish the inducements to good behavior; if a president is particularly avaricious and should face a term limit, he may try to retain the office through the exercise of violence; limits would deprive the public of the president’s experience gained through holding office; if there was ever a time of crisis, limitations will remove capable and experienced leaders from their positions, robbing the people of their leadership; and constitutionally established limits would necessitate a change in government, causing apprehension among the public, drastic shifts in public policy, and inevitably, a weakening of presidential power (Hamilton, 437). He concludes that indefinite term limits provide necessary independence for the President and greater security for the people. The convincing arguments and sheer speed at which the Federalist Papers were distributed ultimately resulted in New York State’s ratification of the Constitution in late July of 1788. Melancton Smith, “who had always considered himself a moderate and reasonable man,” voiced his unconditional support for the Constitution and urged his fellow delegates to do the same (Webking 1987, 511). 1789-1947: CONGRESSIONAL CALLS FOR TERM LIMITATIONS Efforts to restrict presidential tenure did not disappear following the ratification of the Constitution. Perhaps this is because Congressional interest in institutionalizing the two-term tradition was not so much a protection for the people, but a result of general legislative branch fears of losing power to the executive (Willis 1952, 470). In any event, between 1789-1947 no less than 270 resolutions to limit re-eligibility were introduced in Congress. These resolutions increased drastically at the turn of the nineteenth century, with an average of 2.5 per Congressional session, exemplifying that the issue of presidential tenure was a persistent concern for Congress (Willis 1952, 469). Presidential term limits returned to the spotlight during President Jackson’s administration. In his First Inaugural Address to Congress on December 8, 1829, Jackson indicated his support of an amendment to limit presidential tenure stating, “It would seem advisable to limit the service of the Chief Magistrate to a single term of either 4 or 6 years” (Jackson 1829). Armed with the president’s blessing, Congress considered 21 proposals to limit presidential tenure, but each proposal was soundly rejected (Peabody 1997, 591). The first real threat to the two-term tradition arrived during the midterm election year of 1874, when the major political issue was a potential third term for incumbent Ulysses S. Grant (Stathis 1990, 63). Republicans were critical of Grant’s silence on the issue during the campaign season and ultimately blamed him for the party’s midterm losses in key states such as New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania 5 (Stathis 1990, 64). Nevertheless, rumblings of a possible Grant third term continued beyond the election. But the movement was dealt a significant blow in December of 1875, when the House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed the “Springer resolution,” so named for its author, Rep. William M. Springer: “The precedent established by Washington and other Presidents of the United States in retiring from the Presidential office after their second term has become, by universal concurrence, a part of our republican system of government, and that any departure from this time-honored custom would be unwise, unpatriotic and fraught with peril to our free institutions” (Peabody 1997, 591) Not surprisingly, by the time of the 1876 presidential election Grant had decided against running for a third term, citing increased political resistance (Peabody 1997, 591).2 Decades passed before Congress took up the issue of term limits again. In particular, the 69th Congress during the 1920s was very active in its push to limit presidential tenure; several proposals even incorporated key phrases from the Springer resolution (Peabody 1997, 592). However, it would not be until 1947 that Congress would, at long last, achieve success with the passage of an amendment to the Constitution. THE 80TH UNITED STATES CONGRESS AND THE TWENTY-SECOND AMENDMENT After Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced he would be running for a third term, his 1940 campaign began to attract significant public interest. In Congress, a subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee held sixteen days of hearings prior to the election to investigate the merits of a third Roosevelt term as well as the potential to block Roosevelt’s ability to run. Republican presidential candidate, Wendell Willkie, seeking to appeal to his party base, announced that if he were elected his first message to Congress would be to pass a constitutional amendment restricting presidential tenure (Stathis 1990, 65). Despite Willkie’s call for an amendment, Gallup polling suggested that interest throughout the campaign was “tied to the outcome of the election rather than any fundamental principle” (Stathis 1990, 65). On Election Day, Roosevelt carried 38 states and nearly 55% of the popular vote. Four years later, despite declining health, Roosevelt decided to pursue and eventually win a fourth term as president alongside running mate Harry S. Truman. However, after less than three months in office, Roosevelt died in April of 1945 (Stathis 1990, 65). 2 For alternative explanations, especially that Grant simultaneously learned he had terminal throat cancer, see William Farina, Ulysses S. Grant, 1861-1864: His Rise From Obscurity to Military Greatness (Jefferson: McFarland & Co., 2007). 6 One year later, the midterm elections turned heavily in favor of Republicans, who gained overwhelming majorities in Congress for the first time in eighteen years. This allowed Congress to reopen of the debate over term limits. On January 3, 1947, the first day of the first session of the 80th United States Congress, House Judiciary Chairman Earl C. Michener introduced House Joint Resolution 27, a presidential term limit amendment (Stathis 1990, 66). It is important to note that President Truman did not play any role in the process from proposal to ratification (since the amendment would not apply to his presidency), although he did covertly express his support of the amendment through undated memoranda (Davis 1979, 290). Debate and passage of the amendment in both chambers of Congress was intensely political, propelled by “partisan concerns and regional interests… posthumous revenge against Franklin Roosevelt for breaking the two term tradition” (Koenig 1968, 70; Peabody 1997, 594). In the House, debate on the amendment was limited to just two hours, drawing objections from the Democratic minority, including Rep. Adolf J. Sabath of Illinois. “If I am not mistaken, this is the first time that any resolution amending the Constitution…has been brought under a rule which permits only two short hours of debate” (Congressional Record 1947, 841). One of Sabath’s colleagues from Illinois, Republican Rep. Leo E. Allen, chairman of the Committee on Rules, responded by shrugging off any suggestion of partisan maneuvering. He argued that the amendment was of significant importance to the American people, who without a Constitutional amendment would be exposed to a dangerous loss of freedom. “This is not a political question. The importance of the problem [term limits] to the people transcends all political implications and considerations” (Congressional Record 1947, 841). However, Democrats continued their objections over the proceedings. Rep. Thomason of Texas claimed to be speaking for all of his Democratic colleagues when he said, “I have never known or heard of any such enthusiasm for this rush legislation” (Congressional Record 1947, 865). Others claimed that limiting presidential tenure would “fasten a restriction upon the people, prohibiting them from retaining in office for more than two terms a president they desired,” citing Roosevelt’s high popularity as evidence (Willis 1952, 476). When it was time to vote, forty-seven Democrats – thirty-seven who were from the South – voted with all 238 Republicans and supported the measure, perhaps refuting the conventional wisdom that the amendment was a partisan effort (Brown 1947, 448). Debate in the Senate carried on for some time, but Republicans were eventually successful. The measure, passed by Congress on March 21, 1947 and ratified by the requisite number of states on February 27, 1951, legalized limits on presidential tenure and set in stone a character of predictability for the office of the executive. 7 RESEARCH FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS To determine whether the Twenty-Second Amendment has perpetuated the “lame duck” label and weakened presidential power, five key indicators of presidential effectiveness are considered: Those that are in direct control of the president (vetoes and executive orders), Congressional relations (midterm election results and treaties), and presidential performance (public approval ratings).3 1. Public Sentiments Public sentiments are the first indicator to be examined. Presidents have long been cognizant of the public’s degree of support for policy matters. Abraham Lincoln famously said, “Public sentiment is everything. With it, nothing can fail; against it, nothing can succeed. Whoever moulds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes” (Blondheim 2002, 869). In his seminal work, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents, Richard Neustadt agrees, arguing that a president must be popular if he is to successfully persuade and influence (Neustadt 1990, 83). According to historical polling data, most presidents leave office with a lower approval rating than when they were first elected (Gallup 2008). After the ratification of the Twenty-Second Amendment, the electorate knew by law a president could not seek a third term. Therefore, expectations for the second term would likely be lower, translating into decreased presidential popularity and effectiveness. If public opinion should be lower in a president’s second term than in the first, with the greatest decline in the last two years following the midterm election, it would indicate that the lame duck theory holds under the TwentySecond Amendment. Conversely, a rise in popularity during the last two years disproves the lame duck theory. Table 1 contains data collected from the Gallup poll and the question asked was, “Do you approve or disapprove of the way [first and last name] is handling his job as President?” Table 1. Average Approval Ratings for Two-Term Presidents President Eisenhower Reagan Clinton Bush II Average Year in Office 1 2 68% 65% 57 43 48 46 66 72 60 57 3 70% 43 47 60 55 4 72% 54 54 50 58 5 63% 61 57 45 57 6 53% 62 63 38 54 7 63% 49 61 34 52 8 61% 53 60 30 51 Source: Gallup Poll, as compiled by the American Presidency Project. Values rounded to nearest whole number. 3 These indicators were selected as they are more readily recognizable to the electorate than are other possible measures, e.g., vote concurrence, executive agreements, judicial appointments, etc. Future study of these measures may help further shed light on whether there is a causal relationship to lame duck theory or the Twenty-Second Amendment. 8 Upon analysis of Table 1, the lame duck theory holds. With the exception of modest increases during the Clinton and Reagan second terms, it is clear that twoterm presidents since the Twenty-Second Amendment saw declines in public approval over the course of their presidency. Average approval ratings during the first term (57%) were indeed greater than those in the second term (53%). Other researchers have confirmed this disparity by looking broadly at all presidents over the last century (ignoring potential effects of the Twenty-Second Amendment) and demonstrated that presidential first terms have indeed enjoyed far greater approval (55%) than presidential second terms (46.5%) (Abramowitz et al. 1986, 571). Therefore, these findings suggest that the Twenty-Second Amendment’s institutionalization of term limits is at least partially responsible for presidential declines in popularity and waning power and effectiveness during the second term. However, other factors may be at play, particularly relative levels of Congressional support (Light 1999, 28). Even if public approval ratings fall, a president can still be effective should he have strong support from Congress, or vice versa. Paul Light (1999) explains the inverse relationship between congressional support and public opinion, explaining although “public approval cannot create vast gains in Congress, the absence of public approval eventually undercuts potential for success.” Reagan’s presidency is a good example of this relationship. Reagan saw a 14.2% increase in popularity from his first term to the second, despite the fact his support in Congress over that period actually declined by over 27% (Peters 2010). 2. Midterm Election Results The midterm Congressional elections are generally viewed as a referendum on the sitting president’s administration and his policies. With the exception of the 1934, 1998, and 2002 midterm elections, the president’s party has lost seats during every midterm in this past century, with an average midterm loss of 30 congressional seats (Campbell 1985, 1140). Thus, it can be said that the midterm loss is more than just a tendency, but a historical regularity; presidents who are considered lame ducks should see greater party losses during the second midterm congressional elections. In fact, several models have been advanced to test this idea and each has demonstrated that the midterm congressional elections serve as a check on presidential popularity, power, or effectiveness (Tufte 1975; Campbell 1985; Abramowitz et al. 1986; Erikson 1988). This finding holds heightened relevance if applied to a discussion of lame duck presidents. Table 2 details the losses and gains of all two-term presidents since the Twenty-Second Amendment. 9 Table 2. Seats in Congress Gained/Lost by the President's Party in MidTerm Elections Midterm Year Eisenhower (R) 1954 Eisenhower 1958 Reagan (R) 1982 Reagan 1986 Clinton (D) 1994 Clinton 1998 Bush II (R) 2002 Bush II 2006 President House Seats -18 -48 -26 -5 -52 +5 +8 -30 Senate Seats -1 -13 +1 -8 -8 0 +2 -6 Net Gain/Loss -19 -61 -25 -13 -60 +5 +10 -36 Source: Lyn Ragsdale, Vital Statistics on the Presidency. What is immediately clear from the data is that there is a significant difference between losses in a president’s first midterm and second midterm. During the last century, the average seat loss in the first term has been 32 while the seat loss during the second term has been 41 (Campbell 1985, 1152). In part, this is inextricably linked to presidential popularity, the first indicator examined in this study. Therefore, the low popularity of a second-term president should indicate an increase in their party’s seat loss relative to the first term. Eisenhower and Bush II, who both had lower approval in the second term, exemplify this relationship, upholding the lame duck theory. In the case of Reagan and Clinton, both actually lost more seats in the first term than in the second term, corresponding to lower approval ratings during the first term (see Table 1). The below average approval ratings during their first midterm can account for the significant losses for their parties in those elections. The subsequent rise in their popularity by the second midterm election translates into a modest party loss and gain, respectively, disproving the lame duck hypothesis regarding midterm election results. Perhaps the rise in approval and electoral success for Reagan and Clinton during the second term corresponds to grassroots campaigns during their respective presidencies to abolish the Twenty-Second Amendment. For instance, over the last few months of his presidency Reagan began speaking out against the amendment, telling supporters on one occasion that Republicans during 1947 sought to tarnish Roosevelt’s legacy by enacting the Twenty-Second Amendment. “People should be able to vote for who they want and as long as they want,” he declared (Los Angeles Times 1988). Bill Clinton offered a similar opinion saying, “Presidents should be limited to two consecutive terms, then after a time out of office should be able to run again” (Leung 2003). 10 3. Presidential Vetoes Woodrow Wilson once wrote that the president’s veto power is “beyond all comparison, his most formidable prerogative” (Wilson 1956, 52). The exercise of veto power is a well-known but infrequently used tool of the presidency; overuse of the power has, over the course of the modern presidency, signaled increasing weakness on the part of the president (Ragsdale 2009, 365). When a president does employ the veto however, it is overridden rarely. In more than 200 years, Congress has overridden presidential vetoes just over 100 times – seven-tenths of one percent (Ragsdale 2009, 365). About half of these vetoes have occurred since 1946. If the lame duck theory is true, it is expected that two-term presidents since the TwentySecond Amendment will have vetoed a greater number of bills in the second term than in the first, with a rise in veto power over the president’s tenure. This is based on the dwindling support a president may receive from Congress toward the end of his tenure since he will no longer be able to hold office or influence policy matters. Table 3. Presidential Vetoes President Year in Office 1 2 Eisenhower 10 42 Reagan 2 13 Clinton 0 0 Bush II 0 0 Total 12 55 3 4 11 7 11 0 29 5 23 17 6 0 46 6 12 6 3 0 21 7 39 14 5 1 59 8 20 3 5 7 35 24 16 7 4 51 Source: The United States Senate. Summary of Bills Vetoed, 1789-Present. The data in Table 3 indicates that for all two-term presidents since the Twenty-Second Amendment, the percentage of vetoes is greater in the second term (54%) than in the first (46%). Including the second midterm congressional election (during Year 6), the use of the veto power by the president increases to the end of their tenure. In fact, two-term presidents employed the veto power 14.6% more during the final two years of the second term than over the last two years of the first term. This suggests that the lame duck theory is supported; presidents appear to turn to the veto power during the end of their tenure in office. One alternative explanation for these findings is the nature of the pocket veto. By definition, a pocket veto is an indirect action on the part of the president to veto a bill. Over time, this power has been employed by the president most frequently at the end of a two-term congressional session or during intersession adjournments (Spitzer 2001, 724). As a result, the use of the pocket veto will cause the total number of vetoes to rise during the even years of a president’s term (corresponding to the end of a congressional session). A review of Table 3 confirms this cyclical effect; the presidency of Ronald Reagan offers particular insight into this phenomenon. Thus, the pocket veto argument suggests that the term limits 11 imposed by the Twenty-Second Amendment are not as clearly responsible for the increase in vetoes during the final years of a president’s tenure. Another explanation may be the complex relationship between the President and Congress. Particularly with respect to the veto power, the president’s relations with Congress function to “define the success of a president’s performance” on any single occasion (Ragsdale 2009, 367). Jong Lee, a noted scholar on presidential vetoes, concluded by regression analysis, “A significant amount of variation in presidential veto behavior is explained by the president’s background and partisan or electoral factors” more so than any other possible indicator (Lee 1975, 545). 4. Executive Orders Executive orders are the next indicator of presidential effectiveness to be examined. An executive order is a “presidential directive that requires or authorizes some action within the executive branch” and rarely requires approval of Congress (Mayer 1999, 445). Scholars view executive orders as an important policymaking tool that “reflects much more than simple administrative routines or random noise” and demonstrates a president’s ability to “navigate around an uncooperative Congress and combine constitutional and statutory power that is thought to be available” (Mayer 1999, 462). If the lame duck theory is supported, it is expected that two-term presidents since the Twenty-Second Amendment will have issued a greater number of executive orders in their second term than in the first, with the largest number following the second midterm election. This would indicate that presidents perceive a loss of power and effectiveness towards the end of their term and increasingly turn to unilateral powers. Table 4. Executive Orders Issued by Two-Term Presidents President Year in Office 1 2 Eisenhower 80 75 Reagan 50 63 Clinton 57 54 Bush II 54 31 Total 241 223 3 4 5 6 7 8 66 57 40 41 204 44 41 49 45 179 55 45 38 26 164 50 37 38 27 152 60 43 35 32 170 42 40 41 30 153 Source: The Federal Register. Executive Orders Disposition Tables Index. An examination of Table 4 indicates that all two-term presidents since the Twenty-Second Amendment issued a greater number of executive orders in the first term (57%) than the second term (43%). This is statistically significant; two-term presidents are more likely to issue the bulk of executive orders during the first two years of their presidency, with a decline in the number of directives for the duration of their tenure. Since it was expected that the bulk of executive orders would fall during the second term and after the sixth year, these findings do not support the 12 lame duck theory; executive orders issued during the second term remain nearly flat for each respective president. One factor may be responsible for why presidents issued a greater number of executive orders during their first few years. It may be that upon assuming the presidency, new presidents view executive orders as the simplest and quickest way to establish their political and policymaking agenda. For example, during the 2000 presidential campaign, George W. Bush spoke about expanding the White House’s relationship with faith-based and local organizations that support many social needs in the country’s communities. On the first day of the first full week of his presidency, Bush followed through on this campaign promise by signing Executive Order No. 13199 establishing the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives (Bush 2001). This administrative change exemplifies the type of policy behavior evident in a new period of presidential tenure. 5. Treaties Approved Treaty-making powers are contained in a single clause of the Constitution, which states that presidents must obtain the advice and consent of the Senate in order for a treaty to go into effect (Congressional Quarterly 2000, 196). This power of the president has largely been an effective policymaking tool; between 1789 and 1999, “only twenty-one treaties were rejected outright” by the Senate (Congressional Quarterly 2000, 197). If a lame duck phenomenon exists, the number of treaties approved for two-term presidents since the Twenty-Second Amendment should be higher in the first term than in the second term, as a result of decreasing presidential effectiveness and cooperation from Congress. Table 5. Treaties Approved President Year in Office 1 2 Eisenhower 14 17 Reagan 12 17 Clinton 17 24 Bush II 2 19 Total 45 77 3 4 7 23 17 14 61 5 15 15 48 14 92 6 9 8 37 8 62 7 10 17 26 17 70 8 12 12 18 10 52 5 21 35 13 74 Source: 1789-1998: Congressional Quarterly, Agreements and Treaties. 1998-2008: Library of Congress. Based on the number of treaties per year for all two-term presidents since the Twenty-Second Amendment (Table 5), more treaties were approved during a president’s first term (52%) than in the second term (48%). Although this would seem to support the hypothesis, during the last two years of the second term the number of treaties approved by the Senate actually increases. This indicates that presidential effectiveness and power has not been lost during the second term, meaning there does not appear to be evidence supporting the lame duck theory. 13 However, treaty success seems to follow the even-year cyclical pattern described earlier regarding the pocket veto (see Table 3). A review of Table 5 shows in large part this is the case: The number of treaties approved in Congress (more precisely, in the Senate) rises during the even years of a president’s tenure, which corresponds to the end of a two-term congressional session, before falling again during each odd year. It is important to address Bill Clinton’s presidency, since his treaty activities are significantly higher than other two-term presidents. During Clinton’s administration, the Senate approved more treaties (222) than the Eisenhower and Reagan administrations combined (214). The Clinton administration is also unique in that a larger percentage of treaties were approved during his second term (52%) than in the first term (48%). This further refutes the lame duck hypothesis; the greater number of treaties approved during Clinton’s final two years reinforces earlier research that found presidents who perceive eroding presidential power turn to foreign policy matters, including treaty ratification (Klotz 1997, 323; Tseng 2003, 2). CONCLUSIONS Upon analysis of the data, there does not appear to be significant evidence to confirm that a presidential lame duck phenomenon exists as a result of the enactment of the Twenty-Second Amendment. For each indicator of presidential effectiveness examined, other factors appear to play a stronger role with respect to a president’s willingness or unwillingness to alter his agenda. For instance, a majority of the indicators studied – presidential popularity, vetoes, executive orders, and treaties – relative levels of Congressional support, or simply the institutional limitations between the legislative and executive branches, are correlated with the degree to which a president is successful. Therefore, the Twenty-Second Amendment alone has not caused a decline in a president’s power or effectiveness during the second term. Given that the data has not revealed strong evidence to support the lame duck theory, it remains practical to repeal the Twenty-Second Amendment. There are several reasons to support this argument, some of which were alluded to earlier: 1. As Hamilton argued in Federalist No. 72, limits on presidential tenure may very well be “robbing the people” of capable and experienced leadership during times of crisis, thereby tarnishing the principle of democratic participation. 2. The Congressional Record demonstrates that the amendment was largely a result of partisan politics. Commanding an overwhelming majority in Congress, Republicans pushed for passage, believing the amendment an effective way to invalidate Roosevelt’s legacy. 3. The electorate had no voice in the proposal or passage of the TwentySecond Amendment. During the drafting of the amendment, at least two representatives expressed an “open distrust of the people” to decide such 14 a critical constitutional issue (Willis 1952, 476). This was later reflected in the wording of the amendment, which specified ratification by state legislatures, rather than by state conventions. 4. In theory, the electorate has long favored term limitations on presidents and representatives.4 In practice, however, the electorate’s behavior runs counter to the data; incumbents are regularly returned to Washington. In 2006, James MacGregor Burns, writing for The New York Times, revisited his initial assessment of the Twenty-Second Amendment and offered an equally harsh critique of its implications for American democracy: “A second-term president will, in effect, automatically be fired within four years…he does not have to care – he has, in effect, transcended the risks and rewards of American politics…But whether or not a president has a diminished second term, the amendment barring a third term presents the broader and more serious question of his accountability to the people…He will not run again for office. The voters will not be able to thank him – or dump him.” (Burns 2006) Should presidents be allowed to govern without any accountability to the electorate? Following Burns’ logic, any concerted effort to repeal the TwentySecond Amendment ought to attract bipartisan support. Republicans, who seek to broaden the conservative movement, would certainly embrace a third-term Republican president. Democrats on the other hand, would surely jump at the chance to send another Franklin D. Roosevelt to the White House during a time of world crisis. Repealing the Twenty-Second Amendment provides the best chance of restoring accountability and removing the artificial weakening of presidential power perpetuated by a fabled lame duck label. 4 The most recent poll on this issue, conducted by NBC News/WSJ in July 2003, found 67% of respondents “think term limits are a good idea” for officeholders. For additional data see NBC News/Wall Street Journal, July 2003. The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research at University of Connecticut. http://www.ropercenter.uconn.edu/data_access/ipoll. 15 WORKS CITED “Agreements and Treaties, 1789-1998.” Congressional Quarterly: Guide to Congress, Volume 1. Washington: CQ Press, 2000. “Amendment to the Constitution Relating to the Terms of Office of the President.” Congressional Record of the 80th United States Congress 93, no. 1 (1947): 841865. “Executive Orders Disposition Tables Index, 1937-Present.” The Federal Register. http://www.archives.gov/federal-register/executive-orders/disposition.html. (Accessed January 8, 2011). “Lame Duck Presidents Usually See Approval Ratings Rise – December 3, 2008.” Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/112810/lameduck-presidents-usually-seeapproval-ratings-rise.aspx. (Accessed July 15, 2010). “Lame Duck.” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. http://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/lame+duck. (Accessed December 18, 2010). “Reagan to Seek End to Succession Limit – March 25, 1988.” Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/1988-03-25/news/mn-319_1_president-reagan. (Accessed December 18, 2010). “Search Treaties, 1998-2008.” Library of Congress. http://thomas.loc.gov/home/treaties/treaties. (Accessed December 18, 2010). “Summary of Bills Vetoed, 1789-Present.” United States Senate – Statistics and Lists. http://www.senate.gov/reference/Legislation/Vetoes/vetoCounts.htm. (Accessed January 2, 2011). Abramowitz, Alan I, Albert Cover and Helmut Norpoth. “The President’s Party in Midterm Elections: Going from Bad to Worse.” The American Journal of Political Science 30, no. 3 (1986): 562-576. Burns, James MacGregor and Susan Dunn. “No More Second Term Blues.” The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/05/opinion/05burns.html. (Accessed February 20, 2011). Blondheim, Menahem. “‘Public Sentiment Is Everything:’ The Union's Public Communications Strategy and the Bogus Proclamation of 1864.” The Journal of American History 89, no. 3 (2002): 869-899. Brown, Everett. “The Term of the Office of the President.” The American Political Science Review 41, no. 3 (1947): 447-452. Buchanan, Bruce. “The Six-Year One Term Presidency: A New Look at an Old Proposal.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 18, no. 1 (1988): 129-142. Bush, George W. “Executive Order 13199 | January 29, 2001.” The Federal Register. http://www.archives.gov/federal-register/executive-orders/2001wbush.html. (Accessed January 8, 2011). Campbell, James E. “Explaining Presidential Losses in Midterm Congressional Elections.” The Journal of Politics 47, no. 4 (1985): 1140-1157. Crockett, David A. “An Excess of Refinement: Lame Duck Presidents in Constitutional and Historical Context.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 38, no. 4 (2008): 708-721. 16 Davis, Paul B. “The Results and Implications of the Twenty-Second Amendment.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1979): 289-303. Erikson, Robert S. “The Puzzle of Midterm Loss.” The Journal of Politics 50, no. 4 (1988): 1011-1029. Gould, Lewis. The Modern American Presidency. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003. Hamilton, Alexander. “Federalist Paper 71.” The Federalist Papers. New York: New American Library, 1961. _____. “Federalist Paper 72.” The Federalist Papers. New York: New American Library, 1961. Jackson, Andrew. “First Annual Message to Congress.” The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29471. (Accessed December 18, 2010). Johnson, Joel A. “Disposed to Seek Their True Interests: Representation and Responsibility in Anti-Federalist Thought.” The Review of Politics, 66, no. 4 (2004): 649-673. Johnson, Karen S. “The Portrayal of Lame-Duck Presidents by the National Print Media.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 16, no. 1 (1986): 50-65. Ketcham, Ralph L. The Anti-Federalist Papers and the Constitutional Convention Debates. New York: New American Library, 1986. Klotz, Robert J. “On the Way Out: Interregnum Presidential Activity.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 27, no. 2 (1997): 320-332. Kocieniewski, David. “The Lame Duck's Waddle to Oblivion.” The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/19/weekinreview/19basics.html. (Accessed July 15, 2010). Koenig, Louis K. The Chief Executive. New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1968. Korzi, Michael J. “Lame Ducks? The 22nd Amendment and Presidential Second Terms.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 2007. http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p208728 (Accessed July 15, 2010). Lee, Jong R. “Presidential Vetoes from Washington to Nixon.” The Journal of Politics 37, no. 2 (1975): 522-546. Leung, Rebecca. “Debate: Presidential Term Limits.” CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/06/06/60minutes/clintondole/main55736 4.shtml. (Accessed December 18, 2010). Light, Paul C. The President’s Agenda: Domestic Policy Choice from Kennedy to Clinton. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. Mayer, Kenneth R. “Executive Orders and Presidential Power.” The Journal of Politics 61, no. 2 (1999): 445-466. Muren, Gary. “Limitations on Presidential Terms.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 5, no. 2/3 (1975): 11-13. Neustadt, Richard. Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan. New York: Maxwell Macmillan International, 1990. 17 Peabody, Bruce G. and Scott E. Gant. “The Twice and Future President: Constitutional Interstices and the Twenty-Second Amendment.” Minnesota Law Review 83 (1997/8): 565-635. Peters, Gerhard and John T. Woolley. “Data Archive.” The American Presidency Project. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/data.php. (Accessed December 18, 2010). Ragsdale, Lyn. Vital Statistics on the Presidency. Washington: CQ Press, 2009. Silber, Marissa. “What Makes a President Quack? Understanding Lame Duck Status Through the Eyes of the Media and Politicians.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 2007. http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p210893_index. (Accessed July 15, 2010). Spitzer, Robert J. “‘The Law:’ The ‘Protective Return’ Pocket Veto: Presidential Aggrandizement of Constitutional Power.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 31, no. 4 (2001): 720-732. Stathis, Stephen W. “The Twenty-Second Amendment: A Practical Remedy or Partisan Maneuver?” Constitutional Commentary 7 (1990): 61-88. Tseng, Margaret. “Lame Duck Presidents and the Use of Unilateral Powers: An Examination of Monument Proclamations.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 2003. http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p64764_index. (Accessed July 15, 2010). Tufte, Edward R. “Determinants of the Outcomes of Midterm Congressional Elections.” American Political Science Review 69, no. 3 (1975): 812-826. Webking, Robert H. “Melancton Smith and the Letters of the Federal Farmer.” The William and Mary Quarterly 44, no. 3 (1987): 510-528. Willis, Paul G. and George L. Willis. “The Politics of the Twenty-Second Amendment.” The Western Political Quarterly 5, no. 3 (1952): 469-482. Wilson, Woodrow. Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics. New York: Meridian Books, 1956. 18