International Journal of Science Commerce and Humanities Volume

advertisement

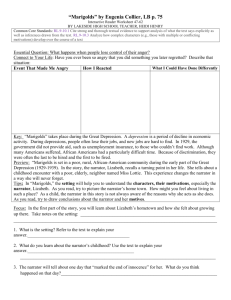

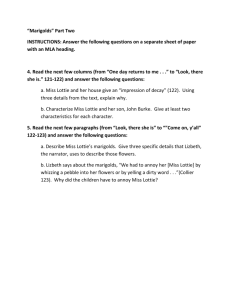

International Journal of Science Commerce and Humanities Volume No 2 No 6 August 2014 “Marigolds”: A Veritable Narrative Owen G. Mordaunt Department of English (Courtesy appts: Black Studies & Foreign Languages) University of Nebraska at Omaha Omaha, NE, USA Abstract: This paper attempts to apply aspects of narrative theory to the short story “Marigolds” by Eugenia Collier. The main focus is the application of personal narrative components suggested by the sociolinguist William Labov since they lend themselves appropriately to the short story. These basic elements relevant to storytelling provide us with an awareness of how people encode information about the world and their personal experiences. INTRODUCTION The short story “Marigolds” (Clarke, pp. 354-63)¹by the African-American writer Eugenia W. Collier is captivating and characterizes a well-written narrative. Collier won the Gwendolyn Brooks Prize for fiction for this story, and it is a story that is widely anthologized and used in many secondary school English classes. Although it is not autobiographical, this piece of fiction haselements that constitute a personal narrative.Obviously, several such stories would subscribe to the designation of personal narrative, but in this paper we apply aspects of narrative theory only to “Marigolds.” NARRATIVES We tell stories for different purposes, and we also enjoy telling stories about ourselves and others. Why do we tell stories?According Ronald Macaulay (2006: 113), we do so “to amuse, to inform, to impress, to ask for sympathy, to illustrate a point, etc.”No wonder Walter Fisher, the communication scholar,argues “that humansare homo narrans, or storytellers, who implicitly and explicitly make sense of their world through narrative” (qtd. in Hall 2005: 207). Personal narratives may have immediate relevance to the narrator‟s life, and should “exemplify a more general point or have some extra-situational value to be entertaining or enlightening”Bonvillain 1997: 267). The intercultural communication scholars Judith Martin and Thomas Nakayama include narratives under histories, which are “stories that we use to make sense of who we are and what we think others are” (Martin & Nakayama: 130). Of course, this has a global dimension, for as Roland Barthes (1975 [1966]: 237) maintains, the narrative is “present at all times, in all societies,” and it “starts with the very history of mankind; there never has been anywhere, any people without narrative; all classes, all human groups, have their stories, and very often those stories are enjoyed by men [people] of different and even opposite cultural backgrounds.” Manfred Jahn (2005: N2.1.2)makes reference to the fact that, in most cases, all theories of narrative differentiate between WHAT is narrated (the “story”) and HOW it is narrated (the “discourse”). Some theorists prefer a restrictive meaning of the term „‟narrative,” and apply it only to verbally narrated texts, while others maintain that “anything that tells a story, in whatever genre constitutes a narrative.”Jahn (2005: N2.2) provides a diagram highlighting the individual types of narratives. Obviously, this diagram is not exhaustive, but it lists representative and typical genres: 49 International Journal of Science Commerce and Humanities Volume No 2 No 6 August 2014 NARRATIVE COMPONENT Categorizing and delineating the patterns of stories, according to Megan Power (2010) is a huge field of study, but she touts the theory by the sociolinguist William Labovas the most influential. Labov(1972) assigns six different components to personal narratives in his essay “The Transformation of Experience in Narrative Syntax”: 1. Abstract: How does it happen? Summarizes the main point or result of the story 2. Orientation: Who/what does it involve, and when/where? Identifies time, place characters 3. Complicating action: Then what happened? Recounts events, in chronological sequence 4. Evaluation: So what? Transmits attitudes or emotions of speaker and/or other characters 5. Result or Resolution: What finally happened? Provides point of story 6. Coda: What does it all mean? Terminates story, so that listeners do not ask, “And what happened?” According to Megan Power (2010), this structure “helps us to understand how people encode information about the world on a personal level. Much of it is applicable to narrative discourse, especially the short story, though not necessarily in this order.”The complicating action and the resolution are necessary, but the other components are optional. In this essay, these six components are applied to the short story “Marigolds.” Set against the backdrop of the Great Depression, this story and describes an incident during the adolescence of a young African-African American girl, Lizabeth, growing up in rural Maryland during the great depression. The 14-year-old narrator 50 International Journal of Science Commerce and Humanities Volume No 2 No 6 August 2014 comes of age after her destruction of Miss Lottie‟s marigolds, triggered by being frustrated when she overhears her unemployed father sobbing to his wife because he cannot provide for his family. After she has destroyed the marigolds and is coming to terms with what she has done, she looks up to see an equally devastated Miss Lottie standing over her. It is at this moment that Lizabeth realizes that her innocence of childhood has gone forever. Abstract Abstract,summarizes the main point or result of the story. The narrator successfully accomplishes this in the second paragraph of the story: Whenever the memory of those marigolds flashes across my mind, a strange nostalgia comes with it and remains long after the picture has faded. I feel again the chaotic emotions of adolescence, illusive as smoke, yet as real as the potted geranium before me now. Joy and rage and wild animal gladness and shame become tangled together in the multicolored skein of fourteen-going-on-fifteen as I recall that devastating moment when I was suddenly more woman than child, years ago in Miss Lottie‟s yard. I think of those marigolds at the strangest times; I remember them vividly now as I desperately pass away the time . . . (Clarke, pp. 354-55) Orientation Orientation identifies time and place (setting) and also the characters. The setting of the story is a shanty-town during the depression. The main character and narrator is the tomboyish Lizabeth. Other characters are her brother Joey, who is three years younger; Miss Lottie, an old lady who is the town‟s outcast; her son John Burke; and other children in the neighborhood who Lizabeth and Joey hang out with. Even though Miss Lottie is picked on by the children and is undeserving of their frustrations, she has the only bright spot in the community: a bed of colorful marigolds she faithfully tends to. Complicating Action The complicating action recounts events in chronological sequence. In the story, Lizabeth, her brother Joey and other children take part in throwing stones at Miss Lottie‟s flowerbed of marigolds just for the fun of it and for the purpose of annoying her. Later that evening Lizabeth overhears her father sobbing to her mother because he is embarrassed about being unemployed andnot being able to take care of his family. Lizabeth has never heard her father cry before, and since she has never considered the vulnerabilities of adults, she wrestles with fear and anger over this situation. She is miserable and cannot sleep, and in this condition she escapes through the window of their house and rushes to Miss Lottie‟s flowerbed to unleash her fury by trampling on the marigolds and uprooting them from the ground. Evaluation The evaluation is concerned with transmitting the attitudes and emotions of the narrator and/or other characters. It is clear when the story opens that the narrator is preoccupied with the conditions under she lives, a hometown she only associates with dust: When I think of the hometownof my youth, all that I seem to remember is dust—the brown crumbly dust of late summer—arid, sterile dust that gets into the eyes and makes them water, gets into the throat and between the toes of bare brown feet. I don‟t know why I should remember only the dust. Surely 51 International Journal of Science Commerce and Humanities Volume No 2 No 6 August 2014 there must have been lush green lawns and paved streets under leafy shade trees somewhere in town: but memory is an abstract paining—it does not present things as they are, but rather as they feel. And so when I think of that time and that place, I remember only the dry September of the dirt roads and grassless yards of the shantytown where I lived. And one other thing I remember, another incongruency of memory—a brilliant splash of sunny yellow against the dust—Miss Lottie‟s marigolds. (Clarke: 354) On reflecting on her childhood, and how impoverished her community was she recounts: The Depression that gripped the nation was no new thing to us, for the black workers of rural Maryland had always been depressed. I don‟t know what it was “just around the corner,” for those were white folks‟ words, which we never believed. Nor did we wait for hard work and thrift to pay off in shining success as the American Dream promised, for we knew better than that too. Perhaps we waited for a miracle. Amorphous in concept but necessary if one was to have the grit to rise before dawn each day and labor in the white ma‟s vineyard until dark, or to wander about in the September dust offering one‟s sweat in return for some meager share of bread. But God was chary with miracles in those days, and so we waited—and waited. (Clarke: 355) What a hopeless and futile situation to find oneself! Result or Resolution and Coda The result or resolutionis a significant narrative component in that it provides the point of the story. Here I also include the coda which terminates the story so that the listeners do not ask, “And what happened?”As Lizabeth unleashes her anger at Miss Lottie‟s marigolds, her brother implores her to stop. She sits in the ruined garden among the uprooted flowers, bawling, but it is too late to “undo what she has done.” Her brother, Joey, is sitting next to her, frightened and not knowing what to say. Then he says: “Lizabeth, look.” She looks up and sees an equally devastated Miss Lottie standing over her. This is the moment marks an end to Lizabeth‟s innocence, but this is not the type of innocence we associate with the loss of virginity. Her interpretation is thus: Innocence involves an unseeing acceptance of things at face value, an ignorance of the area below the surface. In that humiliating moment I looked beyond myself and into the depths of another person. This was the beginning of compassion, and one cannot have both compassion and innocence. (Clarke: 362). Lizabethnow sees with the eyes of an adult, with the eyes of compassion, and she knows that the innocence of childhood is gone forever. Yes, she has learned from her mistakes. CONCLUSION In conclusion, it is fitting to mention that narratives serve teaching functions as suggested by Bradford „J‟ Hall (2005:75). These functions are relevant to: 1. 2. 3. 4. the way the world works (in general principle and in particular context), our place in the world (in terms of both our persona and social identities), how to act in the world (both effectively and appropriately), and how to evaluate what goes on in the world in terms of what is good/bad and safe/dangerous. Even though these pedagogical functions are not elaborated on in this discussion, they have implications for the story “Marigolds” and fit in with the narrative components proposed by Labov. All this is successfully captured in the concluding paragraph of the story: 52 International Journal of Science Commerce and Humanities Volume No 2 No 6 August 2014 The years have taken me worlds away from that time and that place, from the dust and the squalor of our lives and from the bright thing that I destroyed in a blind childish striking out at God-knows what. Miss Lottie died long ago and many years have passed since I last saw her hut, completely barren at last, for despite my wild contrition she never planted marigolds again. Yet there are times when the image of those passionate yellow mounds returns with painful poignancy. For one does not have to be ignorant and poor to find that life is barren as the dusty yards of our town. And I too have planted marigolds. (Clarke: 362-63) NOTES 1. This story is also available www.montgomeryschoolsmd.org. online: PDF Marigolds By Eugenia W. Collier, REFERENCES Barthes, R. (1975[1966]).An Introduction to the Structural analysis.New Literary History, 6: 237-272. Bonvillain, N. (1997). Language, Culture, and Communication: The Meaning of Messages.Upper River, NJ, Prentice Hall. Saddle Clarke, J.H.,ed. (2001). Black American Short Stories: A Century of the Best. New York, Hill and pp. 354-363. Wang, Hall, B. “J”. (2005). Among Cultures: The Challenge of Communication.Belmont, CA, Thomson Wadsworth. Jahn, M. (2005).Narratology: A Guide to the Theory of Narrative. English Department, University Cologne. Labov, W. (1972).The transformation of experience in narrative syntax.In Language in the William Labov. Philadelphia: UPenn Press, pp. 354-396. of Inner City, ed. Macaulay, R. (2006). The Social Art: Language and Its Uses. New York, Oxford UP. Martin, J., &Hakayama, T. (2007).Intercultural Communication in Contexts. New York, McGraw- Hill. Power, M. (2010). Labov‟s 6 Basic Elements of Storytelling. Retrieved 19 February 2010, from http://meganpower.blogspot.com/2010/02/labov_6_basic_elements_of_storytelling. pdf. 53