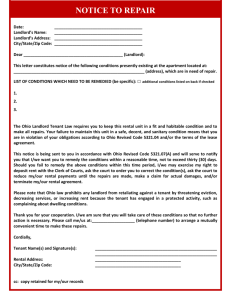

Assignment, Subletting, and Mortgaging by Tenant

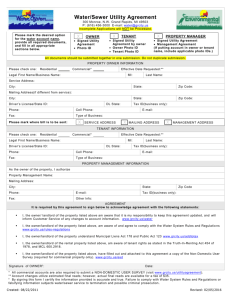

advertisement