Small bowel cancer

advertisement

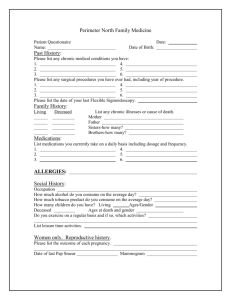

Home > Cancer information > Cancer types > Smallbowel Small bowel cancer Although the small bowel makes up three quarters of the digestive system, cancers in this area are rare. Around 1,000 people in the UK are diagnosed with small bowel cancer each year. On this page The small bowel Types of small bowel cancer Causes and risk factors of small bowel cancer Signs and symptoms of small bowel cancer How small bowel cancer is diagnosed Staging of small bowel cancer Treatment Clinical trials for small bowel cancer Your feelings References and thanks We hope this information answers your questions. If you have any further questions, you can ask your doctor or nurse at the hospital where you are having your treatment. The small bowel The small bowel is part of the digestive system and extends between the stomach and the large bowel (or colon). The small bowel is divided into three main parts: the duodenum, the jejunum and the ileum. The small bowel folds many times to fit inside your abdomen and is around five metres (16 feet) long. It is responsible for the breakdown of food, which allows vitamins, minerals and nutrients to be absorbed into the body. Diagram showing the position and sections of the small bowel Types of small bowel cancer There are four main types of small bowel cancer and they are named after the cells where they develop. The types are: adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, neuroendocrone (carcinoid) tumours and lymphoma. Adenocarcinoma These tumours start in the lining of the bowel. They are the most common type of small bowel cancer and usually occur in the duodenum. Sarcoma These tumours develop in the supportive tissues of the body. There are different types of sarcoma. Leiomyosarcomas usually grow in the muscle wall of the small bowel, most commonly in the ileum. Another rare type of sarcoma is a gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST), which can develop in any part of the small bowel. Neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumours These start from cells that make hormones within the small bowel. These tumours appear most commonly in the ileum and sometimes within the appendix. Lymphoma These tumours start in the lymph tissue of the small bowel. The lymph tissue is part of the body’s immune system. Usually small bowel lymphomas are non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs). They occur most commonly in the jejunum or ileum. Occasionally, a small bowel cancer may be a secondary cancer. This means it has spread from a primary cancer somewhere else in the body. The information on this page is mainly about adenocarcinoma of the small bowel. Causes and risk factors of small bowel cancer The cause of most small bowel cancers is unknown. However, some people with non-cancerous bowel conditions may have a higher risk of developing small bowel cancer. These conditions include Crohn’s disease, coeliac disease and Peutz-Jegher’s syndrome. People who have had a cancer of the colon or rectum, or who have hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), also have an increased risk of developing small bowel cancer. Small bowel cancer, like all cancers, is not infectious and can't be passed on to other people. Signs and symptoms of small bowel cancer The symptoms of small bowel cancer are often vague and difficult to diagnose. They may include any of the following: dark or black stools due to bleeding in the small bowel cramping abdominal pain anaemia (low number of red blood cells) due to blood loss weight loss diarrhoea. These symptoms may be caused by many things other than small bowel cancer but symptoms that are severe, get worse, or last for a few weeks should always be checked by your doctor. Occasionally, the cancer can cause a blockage (obstruction) in the bowel, which may be complete or partial. The symptoms of this are vomiting, constipation, griping pain and a bloated feeling in the abdomen (tummy). Sometimes a blockage in the small bowel can cause the bowel to tear. This is a serious condition that usually occurs suddenly and needs to be treated with surgery. The symptoms include severe pain, shock (a drop in blood pressure) and abdominal swelling. How small bowel cancer is diagnosed Usually you’ll begin by seeing your GP, who will examine you and arrange for any further tests that may be necessary. Your GP will refer you to a hospital specialist for these tests and for expert advice and treatment. At the hospital, the doctor will ask you about your general health and any previous medical problems. They will take blood samples to check for anaemia and examine you to check that your liver is working properly. You may also have a chest x-ray to check your lungs and heart. You may be asked to take a sample of your stool (bowel movement) to the hospital so that it can be tested for blood. The following tests are commonly used to diagnose small bowel cancers. Endoscopy or colonoscopy These tests allow the doctor to look inside the duodenum and the upper part of the jejunum (endoscopy), or the lower part of the ileum (colonoscopy). The test may be done in the hospital's outpatient department or on a ward. You will be asked to lie on your side and given a mild sedative to help you relax. The doctor gently passes a thin tube either down your throat and through your stomach (endoscopy), or into your back passage (colonoscopy). There is a light and lens at the end of the tube to help the doctor to see any abnormal areas. If necessary, a small sample of tissue will be taken (biopsy) for examination under a microscope by a pathologist. Unfortunately, these tests do not reach some areas of the jejunum or the ileum so different tests are needed to find tumours in these areas. Capsule endoscopy This test takes pictures of the whole of the inside of your digestive tract, including all of your small bowel. You swallow a capsule about the size of a large pill. Inside the capsule is a camera, a battery, a light and a transmitter. The camera takes two pictures a second for eight hours. The pictures are sent to a small recording device attached to a belt you wear round your waist. You have to follow a special diet the day before and on the day of the test. Your nurse or doctor will give you instructions about this. Otherwise you can carry on with your normal activities while the camera is taking pictures. About eight hours after swallowing the capsule you will need to return the recording device to the hospital. The pictures from the recorder are loaded onto a computer and will be looked at by your doctor. The capsule is disposable and is usually passed out naturally in bowel motions. If the capsule is not passed out of your system, you may need to have an operation to remove it. Barium x-rays This is a special x-ray of the small bowel, sometimes called a barium meal or barium follow-through. It is done in the hospital x-ray department. For this test it's important that the bowel is empty so that a clear picture can be seen. Your hospital will give you instructions, but it is likely that on the day before your test you will be asked to take a laxative and drink plenty of fluids to help empty your bowel. On the day of your barium x-ray, you should have nothing to eat or drink. You will be asked to drink a fluid that contains barium, a substance that shows up white on an x-ray. The doctor will watch the barium pass through the whole of the small bowel on a screen, to look for any abnormalities. Your stools may be white for a couple of days after the test. This is the barium passing out of your body and is nothing to worry about. The barium can also cause constipation so you may need to take a mild laxative for a couple of days. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan This test uses magnetism, instead of x-rays, to build up a detailed picture of areas of your body. Before the scan you may be asked to complete and sign a checklist. This is to make sure it’s safe for you to have an MRI scan. Before having the scan, you’ll be asked to remove any metal belongings, including jewellery. Some people are given an injection of dye into a vein in the arm. This is called a contrast medium and can help the images from the scan show up more clearly. During the test you will be asked to lie very still on a couch inside a long cylinder (tube) for about 30 minutes. It’s painless but can be slightly uncomfortable, and some people feel a bit claustrophobic during the scan. It’s also noisy, but you’ll be given earplugs or headphones. You'll be able to hear, and speak to, the person operating the scanner. Other tests Sometimes it's difficult to get a clear picture of the small bowel, and biopsies can't always be taken, so diagnosis may be made during an operation. Staging of small bowel cancer The stage of a cancer is a term used to describe its size and whether it has spread beyond its original site. Knowing the type and stage of the cancer helps the doctors to decide on the best treatment. Cancer can spread in the body, either in the bloodstream or through the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is part of the body’s defence against infection and disease. The system is made up of a network of lymph nodes that are linked by fine ducts containing lymph fluid. Your doctors will usually check the lymph nodes close to the small bowel to help find the stage of the cancer. There are four stages of small bowel cancer. Stage 1 The cancer is contained within the lining of the small bowel or has spread into the muscle wall, but has not begun to spread to the lymph nodes or other parts of the body. Stage 2 The cancer has spread through the muscle wall and may affect other nearby structures such as the pancreas. Stage 3 The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes. Stage 4 The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes and also to other parts of the body such as the liver or lungs. If the cancer comes back after initial treatment this is known as recurrent cancer. Treatment Treating adenocarcinoma of the small bowel will depend on a number of factors including your general health, the position and size of the cancer and whether it has spread to other areas of the body. Giving your consent Before you have any treatment, your doctor will give you full information about what it involves and explain its aims to you. They will usually ask you to sign a form saying that you give permission (consent) for the hospital staff to give you the treatment. No medical treatment can be given without your consent. Benefits and disadvantages of treatment Treatment can be given for different reasons and the potential benefits will vary for each person. If you have been offered treatment that aims to cure your cancer, deciding whether to have the treatment may not be difficult. However, if a cure is not possible and the treatment is to control the cancer for a period of time, it may be more difficult to decide whether or not to go ahead. If you feel you can't make a decision about treatment when it’s first explained to you, you can always ask for more time to decide. You are free to choose not to have the treatment and the staff can explain what may happen if you don't have it. You don't have to give a reason for not wanting to have treatment, but it can help to let the staff know your concerns so that they can give you the best advice. Surgery for small bowel cancer Surgery is the main treatment for cancer of the small bowel. Surgery may be used to remove the affected section of the bowel and join the bowel back together. It may also be used if there is a blockage within the bowel. Often it's possible to remove the whole tumour during an operation but this isn’t the case for everyone. The position of the tumour within the bowel and how much of the bowel is involved will determine how extensive the surgery is. It may be necessary to remove part of the stomach, colon, the gall bladder or the surrounding lymph nodes during the surgery. Usually, the bowel can be joined together again during surgery (known as an anastomosis). If for some reason this isn't possible, the end of the bowel will be brought out to the skin of the abdominal wall. This opening is called a stoma and the procedure is known as an ileostomy. A bag is worn over the stoma to collect bowel motions. Usually the ileostomy will be temporary and a further operation to rejoin the bowel can be done a few months later. The ileostomy is very rarely permanent. If the cancer is large and has caused a blockage in the small bowel it is sometimes possible to bypass the tumour. This can be used to relieve the symptoms, even if it's not possible to completely remove the tumour. Your surgeon will explain the operation to you and can answer any questions you may have. Sometimes however, the surgeon may not know exactly what can be done until during the operation. After a major operation you may have to stay in an intensive care ward for a couple of days before being moved back to a general ward. When part of the small bowel has been removed or bypassed, you may need to have a special diet, supplements or medicines. This will depend on the extent of the surgery, and is intended to help with the digestion and absorbtion of food. Your doctor or nurse will explain this to you. Our cancer support specialists can give you further information about having an ileostomy. The stoma care nurse at the hospital will help you look after the stoma for the first few days, and can give you support and information on caring for your stoma when you go home. Radiotherapy for small bowel cancer Radiotherapy is the use of high-energy rays to destroy cancer cells, while doing as little harm as possible to normal cells. It’s not commonly used in the treatment of small bowel cancers. However, for some people it may be used following surgery or in combination with chemotherapy. Chemotherapy for small bowel cancer Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy cancer cells. Chemotherapy may occasionally be used to treat cancer of the small bowel, either in combination with radiotherapy or surgery, or on its own. Fluorouracil (5FU), oxaliplatin (Eloxatin®) and irinotecan (Campto®) are the drugs most commonly used. Chemotherapy is not always suitable and its effectiveness in treating small bowel cancer is still being researched. Follow-up After your treatment has finished, your doctor will ask you to go back to hospital for regular check-ups and x-rays or scans. These are good opportunities to discuss with your doctor any worries or problems you may have. However, if you notice any new symptoms or are anxious about anything else between appointments, contact your doctor or nurse for advice. Clinical trials for small bowel cancer Research into treatments for cancer of the small bowel is ongoing and advances are being made. Cancer specialists use clinical trials to assess new treatments. Before any trial is allowed to take place, an ethics committee must approve it and agree that the trial is in the interest of the patients. You may be asked to take part in a clinical trial. Your doctor will discuss the treatment with you so that you have a full understanding of the trial and what it involves. You may decide not to take part or to withdraw from a trial at any stage. You will still receive the best standard treatment available. Your feelings Having investigations and treatment for cancer can be a very stressful experience. You may have many different emotions including anger, resentment, guilt, anxiety and fear. These are all normal reactions, and are part of the process many people go through in trying to come to terms with their condition. Everyone has their own way of coping with difficult situations. Some people find it helpful to talk to family or friends, while others prefer to seek help from people outside their situation. Some people prefer to keep their feelings to themselves. There is no right or wrong way to cope, but help is there if you need it. Our cancer support specialists can give you information about counselling in your area. References and thanks This information has been compiled using information from a number of reliable sources, including: DeVita, et al. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 8th edition. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. 2008. Kelsen, et al. Gastrointestinal Oncology: Principles and Practice. 2nd edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 2007. Raghavan, et al. The Textbook of Uncommon Cancers. 3rd edition. Wiley. 2006. Thank you to Dr Richard Hubner, Consultant Medical Oncologist and Dr Andrew Webb, Consultant Medical Oncologist. Thanks to people like you Thank you to all of the people affected by cancer who reviewed what you're reading and have helped our information to grow. You could help us too when you join our Cancer Voices Network - find out more. Content last reviewed: 1 January 2013 Next planned review: 2015 We make every effort to ensure that the information we provide is accurate and up-to-date but it should not be relied upon as a substitute for specialist professional advice tailored to your situation. So far as is permitted by law, Macmillan does not accept liability in relation to the use of any information contained in this publication or third party information or websites included or referred to in it. Macmillan Cancer Support, registered charity in England and Wales (261017), Scotland (SC039907) and the Isle of Man (604). A company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales company number 2400969. Isle of Man company number 4694F. Registered office: 89 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7UQ.