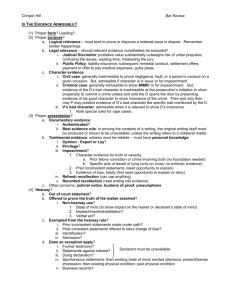

Hearsay and Exceptions to Hearsay Rule

advertisement