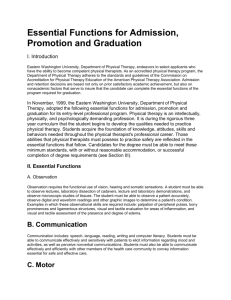

Policy and guidelines on disability and the duty to accommodate

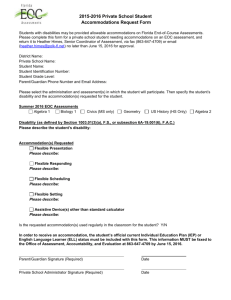

advertisement