Julius Caesar biography

advertisement

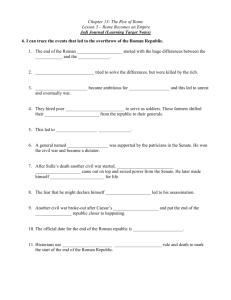

Julius Caesar biography Ch 6 J ulius Caesar was a Roman general and politician who overthrew the Roman Republic and established the rule of the emperors. Caesar used the problems and hardships of the period to create his own supreme political and military power. Roman Julius Caesar is regarded as one of the most powerful and successful leaders in the history of the world. His life and his violent death have been widely celebrated in literature and film. Caesar's first important political success came in 63 B.C.E., when he was elected pontifex maximus, the chief religious office in Rome that carried important political possibilities. Caesar was then elected praetor (an elected Roman official) for 62 B.C.E. and served his propraetorship in Spain. Caesar was quick to take advantage of his power by waging a successful campaign against some native tribes in a Roman province in western Europe. Meanwhile, his political enemies accused him of provoking, or starting, the war. First Triumvirate In 59 B.C.E. Caesar won an election to become consul, or an official ruling over foreign lands. The Senate, immediately moving to block his hopes of future political power, assigned him to lands that offered Caesar no possibilities for military glory. Caesar, who desired more glamorous political and military opportunities, saw that he needed allies to overcome his opponents in the Senate. Caesar soon found the alliance that would become known as the First Triumvirate. He aligned himself with the Roman General Pompey (106–48 B.C.E.), who brought wealth and military might, and Crassus (140–91 B.C.E.), a powerful Roman politician who brought important political connections. The alliance was further sealed in 58 B.C.E. with the marriage of Caesar's only daughter, Julia, to Pompey. Foundations Revolt in Gaul Caesar was awarded the governorship of Gaul (modern day France), a Roman province occupied by several tribes. While Roman control in Gaul was limited, Rome did have political relations with tribes beyond the actual border of the province. Caesar quickly took advantage of these connections and the shifting power position in Gaul to extend the realm of Roman control. Caesar decided to undertake an expedition against Britain, whose tribes maintained close contacts with Gaul. These expeditions in 55 and 54 B.C.E. created great enthusiasm in Rome, as for the first time Roman arms had advanced overseas to conquer new peoples. Caesar probably thought that his main task of conquest was complete. In 52 B.C.E., however, Gaul rose in widespread rebellion against Caesar under Vercingetorix, a nobleman of a tribe in Gaul. This revolt greatly threatened Caesar's power base. At the same time, the political situation in Rome was equally chaotic. The tribune (Roman official) had been murdered, and his death was followed by great disorder in Rome. Caesar had crossed the Alps to watch the changing conditions in Rome. When the news of revolt in Gaul reached him, he recrossed the Alps and rallied his divided army. Caesar's forces lost several battles to Vercingetorix but he made the mistake of taking refuge in the fortress of Alesia, however. Caesar used the best of Roman siege techniques and encircled the fortress to capture the enemy. Soon Vercingetorix was forced to surrender. Dissolving the Triumvirate Caesar's long absence from Rome had partially weakened his political power. At the same time Caesar's conquests were well publicized. His Commentaries, which described the campaigns, circulated among the reading public in Rome. Julius Caesar biography Ch 6 Caesar sought to place his conquests in the best possible light, and the Commentaries stressed the importance of defending the friends and allies of Rome against traditional Roman enemies. He had made vast additions to the Roman Empire (about 640,000 square miles) at the expense of peoples who had long been enemies of Rome. Pompey, on the other hand, had remained in Rome and strengthened his political position by appearing as a leader in a time of chaos. Other tensions in the alliance came with Julia's death in 54 B.C.E., which removed an important bond between the two men. The death of Crassus in 53 B.C.E. further weakened the relationship between Pompey and Caesar. Civil war When Caesar returned to Rome in 50 B.C.E., the Senate looked to put him on trial for acts he committed while acting as consul. Caesar now had two choices: he could bow to the will of the Senate and be destroyed politically, or he could start a civil war. Caesar chose war. It the beginning the greater power seemed to rest with Pompey and the Senate, as Pompey had powerful resources with which to draw support against Caesar. However, Caesar had at his command a tough, loyal, and experienced army, as well as an extensive following in Italy. Most of all, he was fighting for his own interests alone and did not have to face the divisions of interest, opinion, and leadership that plagued Pompey. Pompey quickly decided to abandon Italy to Caesar and fell back to the East. Caesar secured his position in Italy and Gaul and then defeated Pompey at Pharsalus on Aug. 9, 48 B.C.E. Pompey fled to Egypt and was killed by the young pharaoh Ptolemy (63– 47 B.C.E.). Caesar followed Pompey to Egypt and became involved in the struggle for power in the house of Ptolemy, a family in Egypt that ruled for generations. The main result of his time in Egypt was the affair that developed between Caesar and Cleopatra (51–30 B.C.E.), Ptolemy's sister and joint Foundations ruler of Egypt. She would later give birth to Caesar's son, Caesarion. Consolidation of the empire Although his rival was eliminated, much work remained to make Caesar's position secure. He adopted a policy of special clemency, or mercy, toward his former enemies and rewarded political opponents with public office. For himself he adopted the old Roman position of dictator, a ruler with absolute power. There has been much debate about what political role Caesar planned for himself. He certainly thought the old government was weak and desired to replace it with some form of rule by a single leader. Just before his death, Caesar was appointed dictator for life. About the same time, he began issuing coins with his portrait on them, something never before practiced in Rome up to that time. Caesar was planning major improvements to transform the capital of the empire he commanded. New colonial foundations were under way, and he reordered the defective Roman calendar. Death and legacy In Rome, dissatisfaction was growing in the Senate over the increasingly permanent nature of Caesar's rule. A conspiracy was formed to remove Caesar and restore the government to the Senate. The conspirators hoped that, with Caesar's death, government would be restored to its old republican form and all of the factors that had produced Caesar would disappear. The conspiracy progressed with Caesar either ignorant of it or not recognizing the warning signs. On the Ides of March (March 15), 44 B.C.E., he was stabbed to death in the Senate house of Pompey by a group of men that included old friends and allies. With Caesar's murder, Rome plunged into thirteen years of civil war. Caesar remained for some a symbol of an over-dominant leader, and for others the founder of the Roman Empire whose ghost has haunted Europe ever since. For all, he is a figure of genius and courage equaled by few in history.