United States Court of Appeals

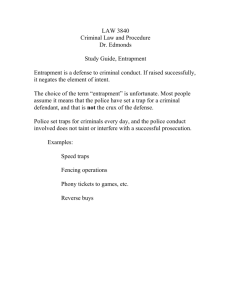

advertisement