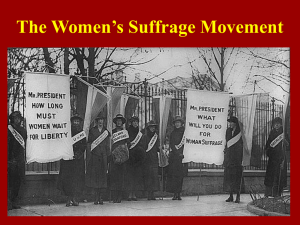

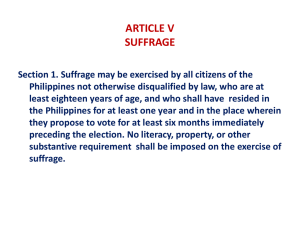

THE EVOLUTION OF SUFFRAGE INSTITUTIONS IN THE NEW

advertisement