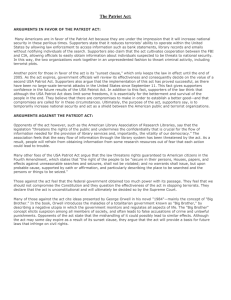

usa patriot act - ACLU of Virginia

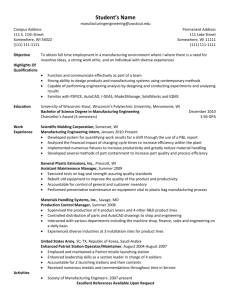

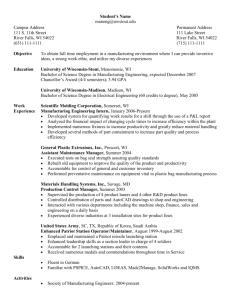

advertisement