Monarchs and the Dilemma with Tropical Milkweed (Asclepias

advertisement

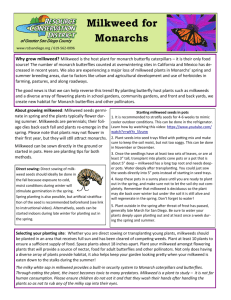

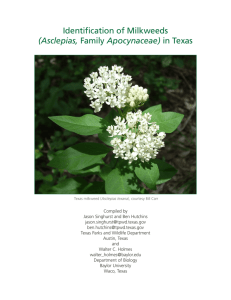

Monarchs and the Dilemma with Tropical Milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) A recent New York Times article highlighted the plight of the Monarch butterfly. Arborist and Master Gardener, Andy Kijewski, has done extensive research to help us understand what can be done locally to support the dwindling habitat of the Monarch butterfly. Hint: not all Asclepias is “good”. In his article, Andy provides names and photographs of Asclepias which will give monarchs a healthy and sustained diet during the bloom season. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/18/science/monarchs-may-be-loved-to-death.html?_r=1) Commercial logging in Mexico's oyamel fir forests where the monarchs overwinter is opening up the canopy and altering the microclimate. In the United States, development and herbicides are shrinking the habitat for monarchs which is increasing the likelihood that in our lifetime, we shall see the end to one of the most fascinating migrations that pass through our own backyards. One of the other problems mentioned in the article (NY Times) and contributing to the end of the monarch’s migration is a non-native milkweed called tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica). It is also called bloodflower or Mexican milkweed. Tropical milkweed is one of the most popular milkweeds sold because of its long bloom period, attractive flowers, and great foliage. It has been sold as an annual in this area however there are reports that it is actually hardy to zone 4. There have also been reports that it may be invasive by heavy re-seeding. Its vigorous growth makes it the favorite of monarchs as larval food, nectar source, and egg laying site. Monarchs actually choose tropical milkweed over native milkweed when planted side by side. However this popularity leads to monarch overcrowding on tropical milkweed which then easily spreads a disease and a parasite not seen on monarchs when feeding on native milkweeds alone. If the monarch survives that and moves on along its migratory journey it may still carry those pests with it potentially infecting others. Tropical milkweed’s steroid-like growth causes it to stay green longer possibly throwing off the monarchs cues as to when to breed and migrate. Native milkweeds, as with all plants, give off volatile compounds. A monarch can pick up the scent of milkweed from 20 miles away. As milkweeds go dormant they give off other volatile compounds that the monarch may use as timing cues to breed and migrate. Visual cues are also picked up by the monarchs as the native milkweed plants start to show their fall colors. Tropical milkweed stays green longer in our area and only withers after a hard frost. In the southeast and southwest tropical milkweed stays evergreen. This has led to some monarchs in the southeast and southwest abandoning their migratory trip to Mexico altogether, exposing themselves to a greater possibility of parasite infection and disease as they never leave the tropical milkweed they are on. But with their Mexican home disappearing, tropical milkweed may be one alternative for some of the monarch’s survival. Do we overlook that Asclepias curassavica is not only not native but possibly invasive in order that some monarchs survive? All native milkweeds support monarchs as larval food although you may see that some native asclepias species being more popular than others. Planting a number of different native milkweeds gives the monarch a wider choice of foliage as one species may be more appealing to lay its eggs on than another depending on site, soil, and weather. Native milkweed is also a nectar source for monarchs along with several non-milkweed plants. Please go to: http://monarchjointventure.org/images/uploads/documents/WFM_Brochure_final.pdf for a comprehensive list of nectar plants for monarchs. The important point is to have a range of plants so there is blooming spring, summer, and fall. Tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) is not on the Connecticut Invasive List. Several counties in California, Louisiana, Texas, Tennessee, and Florida are reporting it as naturalized. Native Connecticut milkweeds: Asclepias amplexicaulis (blunt-leaved milkweed) 1 to 3 feet. Dry fields, open woods, usually in sandy soil. Easy to find seed for sale. A. incarnata (swamp milkweed): Eastern native. Grows 2 to 4 feet with pink flowers. 'Ice Ballet' has white flowers. Prefers moist soil. May bloom first year from seed. Easy to find seed and plants for sale. Monarchs second favorite native milkweed. Asclepias exaltata (poke milkweed) Prefers rich woods and edge of woods. 2 to 6 feet. Easy to find seed for sale. Asclepias purpurascens (purple milkweed) Easy to find seed for sale. Asclepias quadrifolia (four-leaved milkweed) Grows 1 to 2 feet. Dry upland woods. Hard to find for sale. A. syriaca (common milkweed): Eastern native. Grows 2 to 5 feet with fragrant lavender flowers. Prefers dry site. Spreads rapidly by rhizomes. The best way to propagate common milkweed is to dig out a one-foot piece rhizome with above-ground growth. Most favored native milkweed by monarchs. A. tuberosa (butterfly milkweed): Eastern and Southwestern native. Grows 1 to 3 feet with showy orange, red, or yellow flowers. Prefers dry soil. Easy to find by seed/plants for sale. Asclepias variegatea (white milkweed) Grows 1 to 4 feet. Partially shaded, sandy to rocky. Endangered in Connecticut. Hard to find. A. verticillata (whorled milkweed): Eastern native. Grows 1 to 2 feet with narrow, threadlike leaves in whorls and white flowers. Open woods and dry slopes. Easy to find seed/plants for sale. A. viridiflora (green milkweed) Endangered in Connecticut. Hard to find for sale. Seed-started plants can take up to three years to flower. All milkweed seeds should be stratified before planting: put them in a ventilated plastic bag or container of moistened sand or moss, and refrigerate for about four weeks. Don’t allow sand/moss to dry out. Images of native Asclepias from Connecticut Botanical Society