Analysis

Cessna Citation Excel

Midsize cabin comfort, light-jet runway distances

and class-leading climb performance.

By Fred George

Paul Bowen

A

t first glance, you might conclude

that Cessna’s newest Citation has

an identity crisis. For example, if

you were blindfolded, led inside and then

shown the cabin, initially you might

assume that you’re seated in a midsize

Citation VII. On closer examination

you’d discover that this aircraft, however,

has a continuous, dropped aisle, with no

spar intruding through the rear floor of

the cabin. This Citation actually has more

seated head and shoulder room because

its floor has been lowered. And a tape

measure would prove that, compared to a

Citation VII, its interior is slightly longer.

Then, throw in a major challenge for a

midsize business aircraft. Bound for a destination 1,000 miles away, this Citation is

going to depart from a 2,000-foot elevation airport with less than 4,000 feet of

runway on a 75°F (24°C) day.

Don’t cringe. This new Citation also

behaves as though it were a sprightly light

jet, such as an Ultra or Learjet 31A on

short runways. It can climb directly to FL

430 in 18 minutes. No other Citation,

including the Ultra, can match that. In less

than two hours, you will be descending

for landing.

The trip time is two hours, 29 minutes,

about eight minutes longer than the flight

would have taken in a Citation VII. This

aircraft, though, burned 190 pounds less

fuel than the Citation VII on the 1,000mile trip. Notably, this Citation also

would have beaten by a nose the bestselling midsize jet on the 1,000-nm trip,

while saving more than 300 pounds of

fuel, according to B/CA’s 1998 Purchase

Planning Handbook.

What is this aircraft with the apparent

identity problem? It’s the Citation Excel,

an aircraft that combines the midsize

cabin of the CE-650 Citation VII, a

scaled-up version of the CE-560 Citation

Ultra’s wing and second-generation Pratt

& Whitney Canada turbofans. The result

is a combination of cabin volume and

runway performance unmatched by

any previous Citation. No wonder it de-

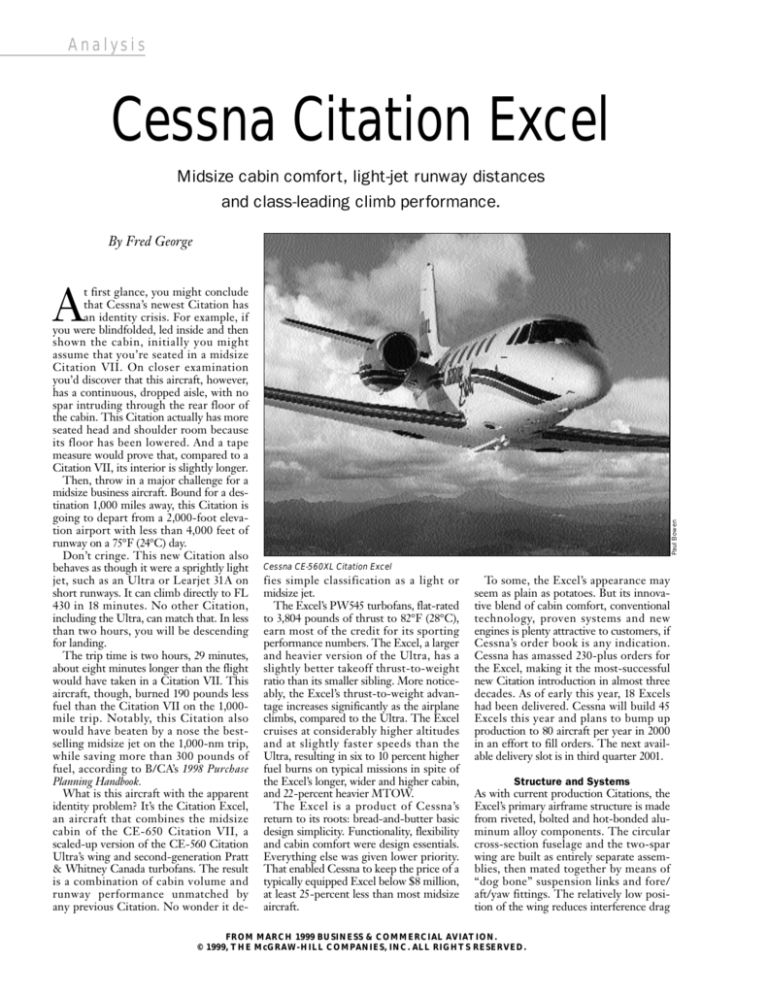

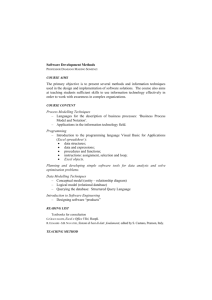

Cessna CE-560XL Citation Excel

fies simple classification as a light or

midsize jet.

The Excel’s PW545 turbofans, flat-rated

to 3,804 pounds of thrust to 82°F (28°C),

earn most of the credit for its sporting

performance numbers. The Excel, a larger

and heavier version of the Ultra, has a

slightly better takeoff thrust-to-weight

ratio than its smaller sibling. More noticeably, the Excel’s thrust-to-weight advantage increases significantly as the airplane

climbs, compared to the Ultra. The Excel

cruises at considerably higher altitudes

and at slightly faster speeds than the

Ultra, resulting in six to 10 percent higher

fuel burns on typical missions in spite of

the Excel’s longer, wider and higher cabin,

and 22-percent heavier MTOW.

The Excel is a product of Cessna’s

return to its roots: bread-and-butter basic

design simplicity. Functionality, flexibility

and cabin comfort were design essentials.

Everything else was given lower priority.

That enabled Cessna to keep the price of a

typically equipped Excel below $8 million,

at least 25-percent less than most midsize

aircraft.

To some, the Excel’s appearance may

seem as plain as potatoes. But its innovative blend of cabin comfort, conventional

technology, proven systems and new

engines is plenty attractive to customers, if

Cessna’s order book is any indication.

Cessna has amassed 230-plus orders for

the Excel, making it the most-successful

new Citation introduction in almost three

decades. As of early this year, 18 Excels

had been delivered. Cessna will build 45

Excels this year and plans to bump up

production to 80 aircraft per year in 2000

in an effort to fill orders. The next available delivery slot is in third quarter 2001.

Structure and Systems

As with current production Citations, the

Excel’s primary airframe structure is made

from riveted, bolted and hot-bonded aluminum alloy components. The circular

cross-section fuselage and the two-spar

wing are built as entirely separate assemblies, then mated together by means of

“dog bone” suspension links and fore/

aft/yaw fittings. The relatively low position of the wing reduces interference drag

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Cessna (3)

Lights in the Excel’s airstair steps, along with a

sturdy folding handrail, help passengers find solid

footing and board with ease.

and keeps the main wing spar from

intruding into the cabin. It also makes

room for a large fuselage to wing fairing

that houses systems components for ease

of maintenance. The battery, for example,

is tucked behind a door in the left side of

the fairing, just aft of the wing.

The primary control surfaces are manufactured from aluminum alloys. Composites are used for the radome, wing/

fuselage fairing and two-section wing

flaps.

The main entry door, a three-step

airstair design, measures 24 inches wide by

54.5 inches tall. Counter springs and gas

shocks make it easy to operate, and triple

seals all but eliminate sound and cold

leaks. Lights in the airstair steps, along

with a sturdy folding handrail, help passengers find solid footing and board with

ease. There is a Type II, plug design,

emergency exit at the right rear of the

cabin, accessible through the lavatory.

Early in the development program,

Cessna made two changes to widen the

center of gravity envelope. Small ventral

fins were added to the aft fuselage to augment the nose-down pitching moment at

stall. And a two-position horizontal stabilizer, hydraulically actuated and linked to

flap position, was fitted to the tail. The

two-position stab, a first for Cessna,

enhances elevator control authority at low

speeds and reduces drag at high speed.

The Excel’s wing, a scaled-up version of

the modified 23000-series wing first developed for the Citation SII, has 3.6 feet

more span than that of the Citation Ultra.

The wing features a wide-chord, swept

leading edge, inboard cuff that increases

the chord-to-thickness “fineness” ratio.

Increasing the chord without changing the

thickness results in a thinner airfoil that

has less drag rise at high speed.

The scaled-up Ultra wing also has a

larger leading radius and a flatter upper

surface, similar to a super-critical airfoil.

This results in a more even pressure distribution along the chord, thus reducing

shock-induced drag.

The PW545’s relatively high altitude

thrust makes it possible to climb directly

to FL 430 at MTOW and routinely cruise

well above the wing’s critical Mach

number, a typical operating characteristic

of high-performance business aircraft. As

a result, Cessna fitted each wing with a

long row of vortex generators to help keep

the airflow attached in order to preserve

fat stability and control margins at, and

above, MMO.

Stability and control characteristics near

the stall limits are enhanced by a variety of

add-on devices. These include leadingedge boundary layer energizers to help

keep the flow attached over the ailerons,

partial stall fences that inhibit span-wise

flow outboard of the swept leading edge

cuff and inboard leading edge stall strips

that provide aerodynamic buffet pre-stall

warning. The small fences near the

wingtips, though, have nothing to do with

aerodynamics. They simply are glareshields for the recognition, position and

strobe lights.

Pilots and passengers take note. Unlike

the notoriously stiff-legged Ultra, the

Excel has long-travel, trailing-link landing

gear that provide exceptionally smooth

landings and a soft ride over bumps on the

taxiways.

The glass windshields, surface sealed to

make them rain repellent, are flanked by

left- and right-side weather windows that

can be opened. Two other fixed pane side

windows are at the rear.

The nose equipment bay is sparsely

populated with standard equipment, pro-

The Excel has long-travel, trailing-link landing

gear that provide exceptionally smooth landings

and a soft ride over bumps on the taxiways.

viding ample room for avionics options.

The aft equipment bay is no hellhole.

Rather, it’s designed for coat-and-tie-clad

pilots. A detachable light is available to

illuminate inspection items. The circuit

breakers and junction boxes, hydraulic

reservoir and air cycle machine all are

within easy view and comfortable reach.

The fire bottles are located above the baggage compartment and need no preflight

inspection because they are electrically

linked to indicators in the cockpit.

The engines are easy to preflight. For

example, snap open the low mounted, oil

filler access doors on the nacelles and

you’ll find oil level sight gauges that eliminate the need to check dipsticks. Leave the

ladder and rags in the line shack.

A standard equipment, vapor cycle air

conditioner, mounted above the baggage

compartment, augments the refrigeration

provided by a three-wheel, air cycle

machine located in the tail cone. Starting

with the 22nd production unit, an

AlliedSignal RE-100 [XL] APU, certificated for inflight operation, will be offered

Twenty-six tiny delta-wing vortex generators prevent airflow separation aft of the shock wave on the

Excel’s wing.

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Cessna (2)

Analysis

The standard aircraft is fitted with a belted potty

seat on the left side of the lavatory, certificated

for occupancy during takeoff and landing.

as a 150-pound, $194,650 exchange option

in place of the vapor cycle air conditioner.

The APU will be approved for use while

refueling and its mounting location does

not intrude in the baggage compartment.

Most of the Excel’s systems are adapted

from earlier 500-series Citations. The primary flight controls, for example, are

pushrod and cable operated. An

aileron/rudder interconnect helps maintain coordinated flight. Nosewheel

steering is mechanically actuated by

“bungee” spring linkage actuated by the

rudder pedals. Trim wheels mechanically

actuate trim tabs on the left aileron, elevator and rudder. Electric pitch trim also

is available.

The landing gear, wing flaps, speed

brakes, thrust reversers and two-position

horizontal stabilizer are powered by an

on-demand, low-pressure, open-center

engine-driven hydraulic system that

straight-wing Citations have used for

three decades. Similar to other Citations,

internal down locks in the landing gear

actuators eliminate the need for safety pins

on the ground. A separate, electrically

powered hydraulic system is used to

power the anti-skid, carbon disc, wheel

brakes.

A pneumatic bottle provides pressure

for emergency landing gear extension and

wheel brake actuation.

Wet wing tanks hold all 6,740 pounds of

fuel. It takes eight minutes to refuel the

aircraft by means of the single-point pressure refueling (SPPR) port located just

ahead of the right wing root. The SPPR

system does not require electrical power

for operation.

Alternatively, over-wing ports may be

used to refuel the aircraft. Anti-icing additives are not required because the engines

have fuel/oil heat exchangers to warm the

fuel. Jet pumps in the wings normally

supply fuel to the engines. Electrically

driven boost pumps in the wings provide

Cessna’s “optional center club plus couch” configuration also features a forward, left-side

refreshment center.

fuel for engine starting, cross feed and in

the event of a jet pump failure.

Engine driven, 28-volt, 200-amp

starter/generators provide DC power for

most electrical equipment, but the electrically heated windshields are powered by

separate, engine-driven AC alternators. A

small solid-state AC inverter powers the

electroluminescent panel lights and an

optional, 117-VAC, 60-cycle inverter is

available to power office equipment in the

The Excel’s P&WC PW545 Engines

Pratt & Whitney Canada’s PW545, currently the most powerful member of the PW500 family, has a thermodynamic

thrust rating of 4,500 pounds. Cessna originally needed

3,640 pounds of thrust for takeoff, but as the Excel grew in

weight to 20,000 pounds MTOW during the development

process, more thrust was needed. The generous thermodynamic rating allowed Pratt & Whitney to dial up thrust to

3,804 pounds for takeoff, up to an ambient temperature of

ISA+13°C, with no degradation in reliability. Wide temperature margins help make possible a 2,500-hour HSI interval

and a 5,000-hour TBO.

The PW545 currently is the highest thrust version of the

PW500-series turbofan family. The basic PW500-series engine, such as the Citation Bravo’s PW530 or Citation Encore’s PW535, has a 4:1 bypass ratio, a one-piece,

titanium, integrally bladed rotor (IBR) fan, powered by a

two-stage low-pressure turbine. The IBR fan weighs 20 percent less than a fan with individual blades and it offers better tip clearance control, resulting in higher pumping

efficiency.

The PW545 shares the same high-pressure core with the

Bravo’s PW530 and Encore’s PW535 engines, but it’s fitted

with a larger, 27.3-inch diameter IBR fan for more thrust. An

axial flow, supercharger stage, mounted on the same shaft

as the fan and ahead of the high-pressure compressors, increases the air flow through the core. The high-pressure turbine is fitted with single cr ystal blades to handle the

additional heat stress and a third stage is added to the lowpressure turbine to power the additional load of the larger

fan and supercharger stage. The overall pressure ratio is approximately 14:1.

The high-pressure core features two axial and one centrifugal compressor stages, a reverse-flow annular combustor and a single-stage, high-pressure turbine. Hot core and

cold fan bypass flows are combined at the tailpipe with a

deep fluted mixer nozzle to enhance thrust output at altitude and to reduce FAR Part 36 noise levels. PW530 and

PW535 turbofans have a conventional hydromechanical fuel

control to keep down the cost.

The PW545, in contrast, has a single-channel electronic

engine control to provide FADEC-like, set-and-forget functionality in flight. Similar to other single-channel EECequipped engines, if the PW545’s engine computer fails,

dispatch is prohibited. Manual reversion to the hydromechanical fuel control is strictly an emergency procedure.

The PW545 produces 932 pounds thrust at 40,000 feet,

ISA, 0.80 Mach, uninstalled, with a specific fuel consumption of 0.709 lbs/lbf/hour. Those numbers are very competi-

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

cabin. A 44-amp/hour NiCad battery provides power for engine starting and serves

as a source for emergency electrical

power. A lead/acid battery is available as a

no-charge option.

The wing leading edges, engine inlets

and fan stators are heated by engine bleed

air when needed for anti-ice protection.

Bleed air flows continuously to the fan

spinners to keep them ice free. Highspeed pneumatic boots deice the leading

edges of the horizontal tail. The pitot

tubes, static ports, total air temperature

probe and angle-of-attack vane are electrically heated for ice protection. The

surface seal coating on the windshields

makes them repel rain. There also is an

electrically powered, rain removal blower.

The 9.3-psi differential pressurization

system uses bleed air supplied by the

engines and/or optional APU. Normally,

the crew only has to set the landing field

elevation prior to takeoff. All other functions are controlled automatically by a

digital pressurization controller. The maximum cabin altitude is 6,800 feet.

Temperature sensors in the cabin and

cockpit are used by the two-zone temperature controller in the cockpit to maintain

a comfortable environment for both passengers and crew. A cabin thermostat,

allowing temperature selection by the passengers, is available as an option.

The standard 50-cubic-foot, or optional

76-cubic-foot, emergency oxygen bottle is

located in the nose equipment bay.

Similar to the Citation Jet, the Excel has

high intensity, flush mount, Fresnel lens

landing lights in the belly fairing, plus

landing/taxi/recognition lights in the wing

leading edges near the tips. A ground

recognition light, in lieu of a mechanically

rotating beacon, is mounted at the top of

the vertical fin. Anti-collision strobe lights

are mounted next to the position lights at

the wingtips, but not at the tail light. Standard equipment also includes tail flood, or

“logo,” lights and left- and right-wing

inspection lights.

Pilots take note. The standard cockpit

layout has the landing gear handle

mounted on the center-left side of the

panel, for single-pilot operations. However, Cessna had not yet achieved a

single-pilot waiver for the Excel by the

time we went to press. As a no-charge

option, the aircraft may be configured

with a right-hand mounted landing gear

handle for two-crew operations.

Passenger Amenities

The Excel has appreciably more usable

cabin volume than a Citation VII. The

cabin is about four inches longer, there is

no intruding wing spar in the aft cabin

Cessna Citation Excel

floor and the floor below the passenger

seats has been dropped 3.5 inches, which

yields more seated headroom and legroom

and lessens the trough depth of the

dropped aisle. The cabin has indirect

ceiling lighting, individual reading lights

at the passenger seats and dropped aisle

lighting.

The cabin windows are triple pane for

thermal and acoustic insulation. Each has

a lever-operated, accordion shade.

Seven fore/aft facing passenger seats are

included in the standard configuration.

The aircraft I flew for this report has a

right-side storage closet, with room for

navigation chart storage just aft of the

cockpit divider, adjoining a side-facing,

two-place divan, with fold-down center

armrest, in place of the aft-facing, seventh

seat.

Cessna’s “optional center club plus

couch” configuration also features a forward, left-side refreshment center that has

a four-pound ice drawer; storage room for

beverage containers, water and a coffee

thermos; plus a wide, shallow drawer for

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Cessna

Analysis

Aft of the entry door, the Excel’s club/couch interior has four seats in club configuration, with two additional forward-facing seats in the rear of the cabin, forward of the lavatory.

box lunch storage. Aft of the entry door,

the club/couch interior has four seats in

club configuration, with two additional

forward-facing seats in the rear of the

cabin, forward of the lavatory. There are

no exposed seat tracks, but each of the six

seats has pitch, rake, lateral position and

swivel adjustments. Each fore/aft seat has

a sliding headrest. The club section has

left- and right-side fold-out executive

tables in the sidewalls. Smaller fold-out

work tables are available for the frontfacing, rear seats.

Optional, half-width pyramid cabinets

are installed in the aircraft I flew, providing additional storage for reading

materials. RJ11 telephone jacks and 117VAC power outlets are available as options

for laptop computer users.

The standard aircraft is fitted with a

belted potty seat on the left side of the

lavatory, certificated for occupancy during

takeoff and landing. Standard equipment

includes an internally serviced, selfflushing potty. The aircraft I flew for this

report, in contrast, has an optional rightside, externally serviced, flushing potty

that is not certificated for full-time occupancy. A left-side belted seat, though, is

available as an option, as is a lavatory sink

with hot and cold running water.

The lavatory compartment also has an

aft, central coat or hanging bag closet and

various small storage compartments.

There is an 81-cubic-foot, 700-pound

capacity external luggage compartment

located aft of the pressure vessel. It’s not

heated or pressurized, but it’s long enough

to accommodate skis or golf clubs. It’s

fully carpeted, well lighted and is accessible by means of a 32.5-inch-wide by

28.4-inch-tall airstair door below the left

engine. A word of caution applies, though.

Pilots will have to watch the center of

gravity limits when loading the baggage

compartment with light passenger loads.

And if the optional 150-pound APU is

installed, the c.g. envelope will limit the

allowable baggage weight further.

As the accompanying specifications box

indicates, the Excel can carry four to five

passengers with full fuel, resulting in a

high-speed cruise range of 1,723 miles.

The Range/Payload Profile chart also

shows that the Excel can fly eight people

1,404 miles at high-speed cruise. Although

the Excel is not a full tanks/full seats aircraft, it can fly four to eight people

between most business destinations in the

United States, against 85 percent probability winds with no more than one fuel

stop.

Flying Impressions

The aircraft I flew for this report had a

12,450-pound BOW, 100 pounds lighter

than the average BOW for the past 10 aircraft delivered. The club/couch configuration adds 36.4 pounds to the standard

aircraft’s BOW and this aircraft has the

optional externally serviced lavatory. However, the lavatory doesn’t have running

water because the operator intends to use it

for comparatively short missions. In addition, the owner deleted the vapor cycle air

conditioner to save weight.

Strap into the left seat of the Excel and

it initially seems like any other 500-series

Citation, except that it has more room up

front. The panel, though, is busier. A

triple-row annunciator panel, similar to

that of a Citation VII, is mounted in the

glareshield. The controls for the three

large-format EFIS tubes are mounted in

the instrument panel. New features and

functions require additional switches and

controls. It only took a few minutes,

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Cessna

though, before the panel’s and console’s

controls, displays and switches felt as

easy to use as those of the original Citation 500.

Our ramp weight was 17,225 pounds,

including 4,500 pounds of fuel and a safety

pilot. With four passengers, we could have

flown more than 900 miles at 400-plus

knots and landed with NBAA IFR

reserves. The PW545s’ electronic engine

controls (EECs) are the next best thing to

FADECs when it comes to reducing

workload in flight. The EECs automatically set thrust when the throttles are

placed in the takeoff, climb or cruise

detents. They also provide overspeed limiting, reduced ground idle speed with

weight on wheels and engine diagnostic

plus malfunction logging functions.

Unlike FADECs, though, the PW545’s

engine computers don’t have automatic

hot/hung/false/wet start protection functions. That’s left up to the flightcrew.

The engine start procedure is virtually

the same as it is in other Citations. Turn

on the battery, press a start button and

advance the throttle to the idle position at

eight percent N2 turbine rpm. A ground

power unit was used for both starts and

the ITTs peaked at about 460°F, well

under the 720°F start redline.

OAT was 0°C, we dialed 30.05 on the

PFDs and standby altimeter displays and

Wichita’s field elevation is 1,332 feet.

Based on a 17,000-pound takeoff weight,

our V speeds were 102 KIAS for the V1

decision speed, 106 KIAS for rotation and

118 KIAS for the V2 one-engine-inoperative takeoff safety speed. According to the

AFM, the FAR Part 25 takeoff field length

was 3,410 feet for the seven-degree flap

takeoff. The takeoff N1 fan speed setting

was 86.4 percent.

The Excel comes equipped with a standard, Honeywell Primus 1000 integrated digital avionics package. Two IC-600 integrated avionics computers in the nose equipment bay form the hub of the huband-spoke architecture system that features left- and right-side, eight-by-seven-inch CRT PFDs, plus a

central eight-by-seven-inch MFD.

Cessna publishes simplified takeoff data

that eliminates the need to use the takeoff

data tables on most departures. The AFM

allows the crew to dial in preset V speeds

for flaps 15-degree takeoffs, if the runway

is at least 5,000 feet long, the pavement is

dry, there is no tailwind, anti-ice is not

required and there are no obstructions in

the takeoff climb path. For example, if we

had selected flaps 15 degrees for takeoff,

the preset bug speed would have been 106

KIAS for V1, 107 KIAS for rotation and

119 KIAS for V2.

With such a cold temperature and comparatively light weight, it took very little

thrust to start the Excel moving from

Cessna’s factory ramp. The carbon brakes,

especially with such cold temperatures,

were more sensitive than the brakes of

other Citations I’ve flown. In addition, the

bungee-operated, nosewheel steering

adapted from smaller 500-series aircraft

was somewhat sluggish for making tight

turns with an aircraft as heavy as the

Excel. However, I quickly became comfortable with taxiing by allowing more

lead time to start and stop turns and by

occasionally using a little differential

thrust and braking.

Visibility from the left seat, while being

very adequate in all directions, isn’t as

good as it is in smaller 500-series Citations

that have narrower cockpits and larger

side windows. For example, traffic and

Excel Avionics

The Excel comes equipped with a standard, Honeywell

Primus 1000 integrated digital avionics package. Two IC600 integrated avionics computers in the nose equipment

bay form the hub of the hub-and-spoke architecture system

that features left- and right-side, eight-by-seven-inch CRT

PFDs, plus a central eight-by-seven-inch MFD. Dual radio

management units, to the right of the MFD in the instrument panel, control the Honeywell Primus II CNI radios, including dual 760-channel VHF comm transceivers, dual VHF

nav receivers, dual Mode S transponders, dual DME transceivers and a single ADF receiver, plus dual digital bus

(noise free) audio control panels. The standard package

also includes a 10-KW Honeywell Primus 880 weather radar

and one Rockwell Collins ALT-55 radio altimeter. Dual LITEF

LCR-93 fiber-optic AHRS and dual Honeywell digital air data

computers, one Loral/Fairchild CVR and an ARTEX 110-4

ELT also are included in the standard package. Standby in-

struments include a Meggitt AMLCD flat-panel attitude and

air data indicator, plus an electromechanical HSI. Dual, 30minute JET emergency batteries furnish the standby instrument power.

The IC-600 avionics computers don’t have provisions for

internal FMS cards. As a result, the Excel is fitted with a

single, console mounted, one-box configuration, Universal

Avionics UNS-1Csp as standard equipment. A second UNS1Csp is offered as an option, installed in an optional doublew

i

d

t

h

console.

A Teledyne Controls (nee Magnavox) MagnaStar C-2000,

two-channel radio-telephone is offered as optional equipment. Other options include an AlliedSignal KHF-950 HF

transceiver, AlliedSignal AFIS or Universal UniLink datalink

communications, AlliedSignal Enhanced GPWS (certification

date TBA) and AlliedSignal TCAS I or II.

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Analysis

Cessna Citation Excel

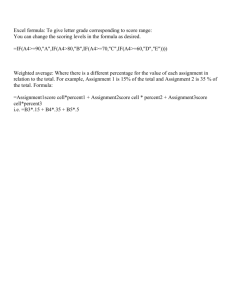

These three graphs are designed to be used together to provide a broad view of Citation Excel performance. Do not use these data for flight planning. For a complete operational performance analysis, use the Approved Airplane Flight Manual and appropriate mission planning data published by Cessna Aircraft.

Time and Fuel Vs. Distance — This graph shows the performance of the Excel at long-range and high-speed cruise. The numbers at the hour lines indicate the miles flown and the fuel

burned for each of the two cruise profiles. Each of the hour points is based on appropriate mission data supplied by Cessna. While flying the Excel for this report, we found Cessna’s

data to be very accurate, if not slightly conservative.

Specific Range — The specific range of the Citation Excel, the ratio of nautical miles flown to pound of fuel burned (nm/lb), is a measure of fuel efficiency. Each curve on this graph is

mathematically derived from four data points supplied by Cessna; thus it is an approximation of the actual change in SFC from long-range to high-speed cruise at the speeds and altitudes depicted on the chart.The sharp decline in SFC in low cruise altitudes and high cruise speeds indicates that the Excel’s strong suit is 400-plus-knot cruise speeds above FL 430,

as shown by the top two curves.

Range/Payload Profile — The purpose of this graph is to provide rough simulations of trips under a variety of payload and airport density altitude conditions, with the goal of flying the

longest distance at high-speed cruise. The payload lines, solely intended for gross simulation purposes, are valid only for the 250-mile marks and endpoint marks. The time and fuel

burn dashed lines are based on high-speed cruise with four passengers with NBAA IFR fuel reserves as shown on the Time and Fuel Vs. Distance graph. Notably, the runway distances

for the Excel are based on flaps 15 degree takeoffs from both the sea-level standard and hot-and-high airports. The flap configuration does not have to be reduced to comply with

one-engine-inoperative, second-segment climb requirements when departing from hot-and-high airports depicted on this chart.

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

obstacles aft of the four o’clock position

are best seen by the copilot.

Once cleared for takeoff, I pushed the

throttles up to the takeoff, or third, detent

in the quadrant. Whoa. I had to ask myself

if this light jet had winglets and a pointy

nose. The acceleration was decidedly

brisk. The N1 stabilized at 86.8 percent

and the total fuel flow was 3,460 pph.

Rotation force was light in spite of our relatively forward center of gravity with just

the crew and one passenger. After flap

retraction and a thrust reduction to the

climb detent, the rate of climb stabilized at

4,500 fpm at 250 KIAS. Twelve minutes

after brake release, we passed through FL

370 in ISA conditions, having burned 350

pounds of fuel. The climb performance

was just as the book predicted, but our

fuel burn was 100 pounds lower than

forecast.

During the climb, basic stability and

control checks revealed that the Excel is

well damped in yaw and short-period

pitch. It also has excellent spiral stability.

It’s as comfortable to hand fly as any other

Citation, including the CitationJet.

After leveling at FL 390 for a quick

speed check, the aircraft stabilized at 0.748

Mach, equivalent to 428 knots at ISA-1°C,

while consuming 1,280 pph. Cessna’s book

values apparently are somewhat conservative. The performance charts predicted

424 knots and a fuel burn of 1,350 pph.

We then climbed to FL 450 for additional cruise speed and high-speed buffet

boundary checks. The climb took three

minutes at a weight of 16,600 pounds,

which is consistent with Cessna’s book

values for a 0.62 Mach cruise climb.

Cessna’s 397 KTAS high-speed cruise and

1,040 pph fuel flow predictions were spoton accurate. Rolling into a turn, I found

that the straight-wing Excel doesn’t have

exceptionally large high-speed buffet margins. Approaching 38 degrees of bank, I

encountered palpable and audible airframe rumble, indicating that the long

array of vortex generators on each wing

isn’t cosmetic. The VGs help keep the airflow attached to the wing up to at least a

1.5-g load factor at high-altitude, highspeed cruise.

Down at FL 430, I performed a basic

long-period pitch stability check. The

Excel’s pitch cycle is well damped and of

relatively long duration.

We then descended to lower altitudes

for air work, deploying the speed brakes

for a trim check. The result was a very

slight nose-down pitching moment,

accompanied by a small increase in speed

and more substantial increase in descent

rate. Retracting the speed brakes produced the opposite result. I noted that the

Tradeoffs are a reality of aircraft design, although aircraft engineers attempt to give each model exceptional capabilities in all areas at an affordable price.

In order to graphically portray the strengths and compromises of specific aircraft, B/CA compares the subject aircraft to the composite characteristics of other aircraft in its class. We average parameters of interest for the aircraft

that are most likely to be considered as competitive among other aircraft in the subject aircraft’s class. We then compute the percentage differences for the various parameters between the subject aircraft and the composite group. We

also include the absolute value of the parameter under consideration, along with the ranking of the subject aircraft

within the composite.

The Excel, though, defies easy classification as a light or medium jet. As a result, we included both light and medium jets in the composite.The group comprises the Citation Ultra, Excel, Learjet 45, Raytheon Hawker 800XP and Citation VII. The Comparison Profile, for example, shows that the cabin of the Excel is highly competitive with other

midsize aircraft. Its payloads with maximum fuel, speed and range, however, are more in line with a light jet. The Price

Index line shows that the Excel has a 14-percent lower purchase price than the composite group, thus providing another perspective on the Excel’s relative strengths and shortcomings.

305 KIAS VMO above 8,000 feet permits

the Excel to keep up with traffic flows into

major airports.

Clean stalls were preceded by generous

airframe buffet, well prior to the stallwarning stick shaker, no doubt a result of

the leading-edge stall strips. Just prior to

the stall, the pitch force became slightly

lighter. At the stall, the nose dropped

gently, nudged down in part by the ventral

strakes, and there was plenty of roll control authority. To recover from the stall, I

used the conventional blend of power up,

pitch down and flaps out. Recovery from a

full aerodynamic stall, though, was not

immediate, especially at the 25,000-foot

altitude limit for such maneuvers. However, the Excel never lost its aerodynamic

composure.

In contrast to the clean stall, there was

much less aerodynamic buffet preceding

the stall with gear and flaps extended.

Mild pre-stall buffet was followed by the

stall-warning stick shaker. Approaching

the stall, the pitch forces became lighter.

At the stall, the nose pitched down with

no hesitation, again helped by the ventral

strakes. Relaxing the yoke pressure,

adding full power and retracting the flaps

to 15 degrees produced a rapid recovery.

Extending the flaps to seven degrees

caused a very mild pitch-down moment.

Extending the flaps also causes the twoposition horizontal stabilizer to move

from one degree nose-up to two degrees

nose-down during a 25-second period,

thus increasing the pitch control of the

elevator authority at slow speeds.

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Analysis

Extending the generously sized flaps

beyond seven degrees produced a noticeable pitch-down moment, although it was

easy to compensate for with pitch trim. I

noted that retracting the flaps caused the

opposite nose-up effect. At a constant

speed, though, the repositioning of the

stabilizer to one degree nose-up caused a

fairly strong nose-down pitching moment.

Normally, however, the aircraft is accelerating while the stab is repositioning to one

degree nose-up, resulting in little pitch

feel change.

With full flaps and a landing weight of

15,700 pounds, we slowed to our V REF

landing speed of 108 knots on the ILS to

Wichita Mid-Continent Airport. Our

charted no-wind landing distance was

2,930 feet. Only 41.9 percent N1 was

needed to maintain speed on the glideslope. The fuel flow was 410 pounds per

side, about the same as in a Citation 500.

Over the threshold, I pulled the thrust

to idle and slowly decreased the pitch

angle. Just above the runway, I flared

slightly nose-up and was rewarded with a

feather-bed touchdown. Note well. This

was not a product of pilot expertise.

Rather, the Excel, in my opinion, simply

has the softest landing manners of any

Citation built.

We reconfigured for takeoff and executed a touch and go to the visual pattern.

The second landing, to a full stop, produced identical results at touchdown. I

deployed the thrust reversers to cut

residual thrust and used a few thousand

extra feet of runway to stop. Some operators say that using full reverse thrust

causes the tail to rumble, but I didn’t

encounter vibration with my low reverse

thrust settings.

The next takeoff was a simulated oneengine-inoperative exercise. Retarding the

thrust lever to idle on the right engine

after V1 produced moderate yaw, which I

overcame with a moderate push of the

rudder pedal. At a V2 takeoff safety speed

of 118 KIAS, the 15,500-pound aircraft

climbed at 1,300 fpm. There was plenty of

thrust on one engine to fly around the pattern and reposition for our final landing.

Total flight time was one hour, 33 minutes, with a block time of one hour, 45

minutes. The total fuel burn was 1,950

pounds.

Conclusion? The Excel has the sporting

thrust-to-weight feel of a Bravo or an

Ultra, the most-refined slow-speed handling characteristics of any straight-wing

Citation and the softest touchdown and

taxi ride. Its ability to sprint up to FL 430

to 450 on all missions and cruise at 400

to 430 knots results in block times on

typical trips that are quite competitive

Cessna Citation Excel

SPECIFICATIONS

B/CA Equipped Price . . . . . . . . . .$7,574,000

Characteristics

Wing Loading . . . . . . . . . . . . .54.1

Power Loading . . . . . . . . . . . .2.63

Noise (EPNdB) . . . . . . . . . . . .74.2/93.1

Seating . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2+8/11

Dimensions (ft/m) . . . . . . . . . . . .See Three Views

Power

Engine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2 PWC PW545

Output/Flat Rating OAT°C . . .3,804 lb ea/

ISA+13°C

Inspection Interval . . . . . . . . .5,000 hrs

Weights (lb/kg)

Max Ramp . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20,200/9,163

Max Takeoff . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20,000/9,072

Max Landing . . . . . . . . . . . . .18,700/8,482

Zero Fuel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14,500/6,577

BOW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12,550/5,693

Max Payload . . . . . . . . . . . . .1,950/885

Useful Load . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7,650/3,470

Executive Payload . . . . . . . . .1,600/726

Max Fuel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6,740/3,057

Payload with Max Fuel . . . . . .910/413

Fuel with Max Payload . . . . . .5,700/2,586

Fuel with Executive Payload . .6,050/2,744

Limits

MMO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0.750

FL/VMO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .FL 289/305

PSI . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9.3

Climb

Time to FL 370 . . . . . . . . . . . .14min

FAR 25 OEI rate (fpm) . . . . . .699

FAR 25 OEI gradient (ft/nm) . .352

Ceilings (ft/m)

Certificated . . . . . . . . . . . . . .45,000/20,412

All-Engine Service . . . . . . . . . .44,000/19,958

Engine-Out Service . . . . . . . . .28,600/NA

Sea Level Cabin . . . . . . . . . . .25,230/11,444

Certification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .FAR Part 25, 1998

with medium jets having higher cruise

speeds, but the Excel’s fuel consumption is

lower.

Sensible Citation

Thirty years ago, Cessna introduced the

“sensible,” albeit slow, Citation, which was

intended to be a comfortable, docile handling business aircraft with simple

systems, solid reliability and low operating

costs. The Excel, although having a much

larger cabin, embraces the same design

philosophy. It has plenty of room for six to

eight passengers, plus a copious external

baggage compartment. It was designed for

excellent maintenance accessibility. Pilots

undoubtedly will laud its handling ease

and forgiving nature. CFOs will appreciate

its operating economy, matched by few

midsize aircraft.

Cessna, however, seems to have left

behind two memorable attributes of the

early 1970s vintage Citations: high drag

and low thrust. The modified wing and

peppy PW545 engines endow the Excel

with spirited climb and cruise performance unmatched by any previous

500-series Citation, including the spirited

Ultra.

The accompanying Comparison Profile

also says plenty about the Excel’s virtues.

We lumped it into a group with the Citation Ultra, Learjet 45, Hawker 800XP and

Citation VII. Compared to the composite

average, the Excel’s cabin is slightly

shorter, but it offers more headroom and

width. Its maximum payload and available

fuel with maximum payload aren’t in a

class with the best midsize jets, but the

Excel wasn’t designed for long-range

missions.

Look at the tallest columns on the chart.

The Excel’s light-jet wing loading and

strong thrust-to-weight ratio make

its runway performance and time to

climb numbers soar above the average.

The right side of the chart indicates

that the Excel doesn’t have the range,

speed or payload carrying capability of a

medium jet, but that’s in keeping with its

design.

All those comparisons assume purchase

price is not a consideration. Add in the

Price Index line and it’s a far different

story. With a B/CA-equipped price

14 percent below the composite, the Excel simply excels compared to the

composite average. Its lead over the composite group ranges from as little as three

percent to as much as 32 percent in some

categories.

The Price Index may help explain the

Excel’s sales success. When compared

with other midsize aircraft, it doesn’t offer

the same range, payload or cruise speed.

But with a $3-million-plus lower price

than a typical midsize aircraft, operators

seem willing to discount the long-mission

performance differences in favor of the

large cabin, short-field performance and

quick times to climb.

Cost and value, cabin comfort and airport performance, simple systems and

reliability, all are important factors for

operators. As a result, the Excel is off to a

strong start in the market. B/CA

FROM MARCH 1999 BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION.

© 1999, THE McGRAW-HILL COMPANIES, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.