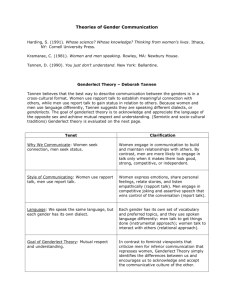

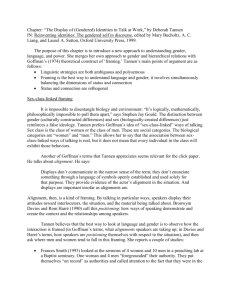

Genderlect: Language, Gender, and Online Communication

advertisement