read petition to the supreme court of california

advertisement

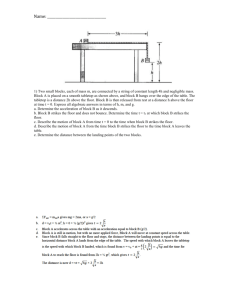

Appellate Court Case No. A118979 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, Plaintiff/Respondent, v. ALI FOROUTAN, Defendant/Appellant ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) Supreme Court No.______ Marin County Superior Court No. SC 114626 A The Honorable John S. Graham PETITION FOR REVIEW AFTER DECISION BY THE COURT OF APPEAL, FIRST DISTRICT MICHAEL S. ROMANO, Esq., No. 232182 MICHAEL CORREL (Law Student) NICHOLAS XENAKIS (Law Student) MILLS CRIMINAL DEFENSE CLINIC STANFORD LAW SCHOOL 559 Nathan Abbott Way Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: (650) 736-8670 mromano@stanford.edu Attorney For Petitioner Ali Foroutan TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................................................iii PETITION FOR REVIEW............................................................................1 QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW .......................................................................2 REASONS FOR REVIEW ...........................................................................3 I. This Court Has Never Adequately Defined the Bounds of Discretion in Three Strikes Sentencing................................................................3 II. This Court Has Never Evaluated the Three Strikes Law Under the State and Federal Bans on Cruel and Unusual Punishment ...............4 STATEMENT OF THE CASE .....................................................................6 STATEMENT OF THE FACTS...................................................................6 ARGUMENT ................................................................................................8 I. THIS COURT SHOULD DEFINE THE “SPIRIT” OF THREE STRIKES LAW TO MAKE THE WILLIAMS-ROMERO ANALYSIS CONSISTENT THROUGHOUT CALIFORNIA.........8 A. The Lack of a Unified Definition of the “Spirit” of the Three Strikes Law has Produced Multiple District Splits and Wildly Divergent Sentences ........................................................................8 B. Ballot Materials As Well As The Statements of District Attorneys Throughout California Declare That Three Strikes Should Only Be Reserved For the “Worst Of The Worst.” .....................................10 C. The Trial Court Below Abused Its Discretion Because Petitioner Falls at Least Partially Outside the “Spirit” of the Three Strikes Law Under Every Existing Definition...........................................11 II. PETITIONER’S SENTENCE IS CRUEL AND UNUSUAL AND REQUIRES REVERSAL UNDER BOTH THE STATE AND FEDERAL CONSTITUTION..........................................................13 i A. This Court Has Never Analyzed The Three Strikes Law Under The Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution..........14 B. This Court Has Never Analyzed The Three Strikes Law Under The California State Constitution Ban on Cruel and Unusual Punishment. ..................................................................................16 III. PUNISHING PETITIONER AGAIN FOR HIS BURGLARY PRIOR CONVICTIONS VIOLATES THE DUE PROCESS REQUIREMENTS SET FORTH IN THE FOURTEENTH AND FIFTH AMENDMENTS OF THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTION. 18 CONCLUSION ...........................................................................................18 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES STATE CASES In re Varnell (2002) 115 Cal.Rptr.2d 464 .....................................................3 People v. Alvarez (1997) 14 Cal.4th 968...............................................3, 8, 9 People v. Carmony (2005) 127 Cal. App. 4th 1066 ..........................5, 13, 16 People v. Gaston (1999) 74 Cal.App.4th 310 ...............................................3 People v. McGlothin (1998) 67 Cal.App.4th 468..........................................3 People v. Romero (2002) 99 Cal.App.4th 1418 ......................................5, 16 People v. Strong (2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 328 ................................................3 People v. Taylor (2000) 95 Cal.Rptr.2d 357 .................................................3 People v. Zichwic (2001) 94 Cal.App.4th 944 ..............................................3 Ramirez v. Castro (9th Cir. 2004) 365 F.3d 755...........................4, 5, 13, 14 STATUTES Health & Safety Code § 11377(a) .................................................................6 Pen. Code § 1385.........................................................................................11 Pen. Code § 290(g)(2) .................................................................................12 FEDERAL CASES Banyard v. Duncan (C.D.Cal 2004) 42 F. Supp. 2d 865 .....................passim Ewing v. California (2003) 538 U.S. 11..................................................4, 14 Gonzalez v. Duncan (9th Cir. 2008) 551 F.3d 875 .......................4, 5, 13, 14 Harmelin v. Michigan (1991) 501 U.S. 957..........................................20, 21 In re Lynch, 8 Cal.3d 410 (1972) ................................................................16 People v. Williams (1998) 17 Cal.4th 148...............................................3, 11 Riggs v. California (1999) 525 U.S. 1114.....................................................4 Solem v. Helm (1983) 463 U.S. 277 ..................................................5, 14, 15 OTHER AUTHORITIES Ballot Pamp., Gen. Elec. (Nov. 8, 1994), Argument in Favor of Prop. 18411 Cal. District Attorneys Association, Prosecutors’ Perspective on California’s Three Strikes Law: A 10-Year Retrospective (2004), “Individual Perspectives” ........................................................................11 Note, A Swing and a Miss: California’s Three Strikes Law (1996) 17 Whittier L.Rev. 651 ...................................................................................9 Paulson, Solano County District Attorney, From the Editor’s Desk (2007) 1 J. INST. FOR ADVANCEMENT CRIM. JUST. 4.......................................10, 11 iii Scully, IACJ President’s Message (2007) 1 J. INST. FOR ADVANCEMENT CRIM. JUST. 2 ...........................................................................................11 Vitiello, Reforming Three Strikes’ Excesses (2004) 82 Wash. L.Q. 1..........9 Zimring et al., Punishment and Democracy/Three Strikes and You’re Out in California (2001)........................................................................................9 iv PETITION FOR REVIEW TO THE HONORABLE CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT, AND THE ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA: ALI FOROUTAN respectfully petitions for review following the decision of the Court of Appeal, First Appellate District, (per Hon. Timothy A. Reardon, Acting P.J.), filed on February 4, 2009. A118978. (Ex. A.) 1 QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW Petitioner’s life sentence for 0.03 grams of methamphetamine represents the harshest sentence ever handed down under California’s Three Strikes law. The fact that petitioner represents the most extreme Three Strikes sentence in the California history was not disputed by the government or the Court of Appeal below. According to Petitioner’s research, every other case involving a Three Strikes sentence involved a defendant with a more severe criminal history or more severe instant offense. Given these facts: 1. Was it an abuse of discretion to sentence Petitioner to life in prison under the Three Strikes law for simple possession of 0.03 grams of methamphetamine? 2. Does a life sentence for possession of 0.03 grams of methamphetamine violate the State or Federal constitutional bans on cruel and unusual punishment? 3. Did the trial court violate the Due Process Clause when it placed primary emphasis on prior convictions when imposing Petitioner’s sentence? 2 REASONS FOR REVIEW I. This Court Has Never Adequately Defined the Bounds of Discretion in Three Strikes Sentencing. In People v. Williams (1998) 17 Cal.4th 148, 161, this Court held that a life sentence under the so-called “Three Strikes law” should only be imposed when a defendant falls within “the spirit” of the recidivistsentencing scheme. 1 Since Williams, this Court has never defined that “spirit” or the bounds of discretion under the Three Strikes law. The lack of guidance from this Court has lead to a “wide divergence in charging and sentencing practices under the Three Strikes law.” (Ex. A at 16.) 2 For example, in People v. Alvarez (1997) 14 Cal.4th 968, a defendant with prior burglary convictions and facing a Three Strikes sentence for simple possession of methamphetamine was instead sentenced 1 A court reviewing a Three Strikes sentence “must consider whether, in light of the nature and circumstances of [the defendant’s] present felonies and prior serious and/or violent convictions, and . . . his background, character and prospects, the defendant may be deemed outside the scheme’s spirit.” Williams, 17 Cal.4th at 161. 2 See also In re Varnell (2002) 115 Cal.Rptr.2d 464, 476 (holding that uncertainty as to the meaning of the “spirit” of the Three Strikes law has created an “amorphous” standard amongst the various California appellate districts); People v. Zichwic (2001) 94 Cal.App.4th 944, 960; People v. Strong (2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 328, 332; People v. Taylor (2000) 95 Cal.Rptr.2d 357, 366-67; People v. Gaston (1999) 74 Cal.App.4th 310, 321; People v. McGlothin (1998) 67 Cal.App.4th 468, 476. 3 to a misdemeanor term in county jail. Petitioner’s instant offense and criminal history is indistinguishable from the defendant in Alvarez, yet he is serving a life sentence. Furthermore, if Petitioner had been convicted in Los Angeles, he would not have been charged under the Three Strikes Law at all. 3 The disparity in sentencing options in these Three Strikes cases has made appellate review meaningless. In her concurrence to the lower court opinion, Justice Rivera explored this issue extensively. (Ex. A.) Resolving this issue will both secure uniformity of decision throughout California and settle an important issue of state law pursuant to Rule 8.500(b)(1). II. This Court Has Never Evaluated the Three Strikes Law Under the State and Federal Bans on Cruel and Unusual Punishment. This Court has never addressed the cruel and unusual punishment issues presented by the Three Strikes law. (See Riggs v. California (1999) 525 U.S. 1114, 1115.) Instead, only federal courts have addressed the relationship between the Three Strikes law and the prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. (See, e.g., Ewing v. California (2003) 538 U.S. 11; Gonzalez v. Duncan (9th Cir. 2008) 551 F.3d 875; Ramirez v. Castro (9th Cir. 2004) 365 F.3d 755; Banyard v. Duncan (C.D.Cal 2004) 42 F. Supp. 2d 865; Duran v. Castro (E.D.Cal. 2002) 227 F. Supp. 2d 1121.) 3 See Three Strikes Policy, Dec. 19, 2000, available at http://da.co.la.ca.us/3strikes.htm (describing that it is the policy of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office to only charge a defendant under Three Strikes when the third strike is a serious or violent felony). 4 Significantly, each federal court to reverse a Three Strikes sentence under as cruel and unusual punishment has done so in a case where the defendant committed a more serious instant offense or had a more serious criminal history than Petitioner. (See Gonzalez, supra, 551 F.3d 875 (prior sex offense convictions); Ramirez, supra, 365 F.3d 755 (prior robberies); Banyard, supra, 42 F. Supp. 2d 865 (assault); Duran, 227 F. Supp. 2d 1121 (kidnapping).) The lack of state authority has produced conflicting results in California’s various appellate districts. Most notably, the California Courts of Appeals have developed divergent views on how to evaluate Three Strikes sentences against claims of cruel and unusual punishment under the state and federal constitutions. For instance, in People v. Carmony (2005) 127 Cal. App. 4th 1066, the court struck down a three strikes sentence as cruel and unusual punishment applying a legal framework articulated by the United States Supreme Court in Solem v. Helm (1983) 463 U.S. 277, 292. While in People v. Romero (2002) 99 Cal.App.4th 1418, another court upheld a Three Strikes sentence for a similarly situated defendant, rejecting the framework applied in Carmony. The Court of Appeal in Petitioner’s case applied yet another standard, holding that no constitutional analysis is required as long as a sentence conforms to the statutory language. (Ex. A at 9.) 5 Resolving this issue will both secure uniformity of decision throughout California and settle an important issue of state law pursuant to Rule 8.500(b)(1). STATEMENT OF THE CASE On April 30, 2002 Petitioner was convicted of possession of 0.03 grams of methamphetamine in violation of Health and Safety Code section 11377(a). 4 On January 26, 2005 the trial court denied Petitioner’s motion to strike two prior strikes and sentenced him to a term of 25 years to life pursuant to the Three Strikes law. (CT 171-74.) On February 4, 2009, California Court of Appeal, First Appellate District, Division Four, in case number A118978 affirmed the trial court’s decision. The Court of Appeal decision became final on March 6, 2009. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS The Hon. Maria P. Rivera provided the following summary of the case in her concurrence to the lower court opinion: [Petitioner’s] three burglaries committed in 1989— comprising the first strike—were unquestionably serious crimes, not merely because the law holds them to be serious but because they involved extensive ransacking of the burgled homes and the theft of many thousands of dollars worth of items, including a “ ‘family heritage’ ” gun collection. Nevertheless, the 1990 presentence report concluded that the 4 In his original trial, Petitioner was also convicted of using an access card without consent of the cardholder. That conviction was reversed by the California Court of Appeal, First District, Division Four in People v. Foroutan (Jan. 26, 2005, A101159) 2005 Cal. App. Unpub. LEXIS 643. The charge was subsequently dismissed. (Ex. A at 2.) 6 burglaries were not so serious as to justify the upper term; sentencing was recommended at the midterm because the “[c]ircumstances in mitigation and aggravation are relatively balanced.” The court sentenced defendant to six years eight months in prison, but execution of the sentence was suspended on condition of one year of county jail time, five years probation, residential drug treatment and restitution. So, despite the seriousness of these crimes, the court did not consider defendant to be particularly dangerous or to require lengthy incarceration. The second strike was a 1992 burglary Foroutan committed while on probation. In contrast to the previous crimes, it was a minor offense. It involved the breaking or forcing of a window in an attempt to enter the home of an individual who, it was argued, was an acquaintance. Defendant and his accomplice were “chased away” by the homeowner. Foroutan did not complete the break-in, steal any items, or threaten the occupant. After pleading guilty, Foroutan served approximately five years in prison. The third strike sentencing offense, of which Foroutan was convicted, was possession of 3/100ths of a gram of methamphetamine. At the same time, he was charged with, but acquitted of, burglary. He was also convicted of a related credit card offense, but that charge was dismissed by the district attorney in the “furtherance of justice” after reversal of the conviction for instructional error. Foroutan consistently stated that his crimes were fueled by his drug habit. He began abusing alcohol and drugs at an early age. As a child, Foroutan was subjected to abusive treatment by his father and harassment by his classmates. Foroutan’s father also abused alcohol and drugs. At sentencing Foroutan was supported not only by family members, but also by one of his former victims who actively opposed imposition of a sentence of 25 years to life. An alcohol/drug assessment conducted by Foroutan’s counselor while he was incarcerated, stated that Foroutan’s “motivation is in the right place to make some remarkable changes in his life.” The report concluded that Foroutan was amenable to treatment, but only in a “long term highly structured 7 Residential Treatment Program such as Delancey Street.” Foroutan had applied to and was accepted by Delancey Street and “seems highly motivated to enter and complete” the program. “Prognosis is favorable due to client’s motivation.” Foroutan was 38 years old at the time of his sentencing in July 2007. No one contends that Foroutan has ever engaged in violent criminal behavior, or in violence of any kind. Had the trial court granted Foroutan’s motion to strike one of the strikes, his maximum sentence would have been six years in prison. (Health & Saf., Code, § 11377, subd. (a); Pen. Code, §§ 18, 1170.12, subd. (c)(1).) ARGUMENT I. THIS COURT SHOULD DEFINE THE “SPIRIT” OF THREE STRIKES LAW TO MAKE THE WILLIAMS-ROMERO ANALYSIS CONSISTENT THROUGHOUT CALIFORNIA. A. The Lack of a Unified Definition of the “Spirit” of the Three Strikes Law has Produced Multiple District Splits and Wildly Divergent Sentences. Petitioner’s life sentence is an example of “[t]he wide divergence in charging and sentencing practices under the Three Strikes law.” (Ex. A at 16.) Justice Rivera’s concurrence highlights the split amongst California’s Appellate Circuits—a split that is “likely to undermine public trust in the Three Strikes law and our criminal justice system.” (Id.) In a stark contrast to Petitioner’s position, in People v. Alvarez (1997) 14 Cal.4th 968, this Court affirmed a trial court’s determination that a life sentence under the Three Strikes law was not appropriate for a 8 defendant convicted of possessing 0.41 grams of methamphetamine with four prior residential burglary convictions. (Alvarez, supra, 14 Cal. 4th at pp. 973, 981.) The facts in Alvarez are remarkably similar to Petitioner’s situation. In Alvarez, however, the defendant not only avoided a life term but was sentenced to a misdemeanor and served one year in county jail. (Id. at pp. 973-74.) As Justice Rivera noted in her concurrence to the lower court opinion the increasing inconsistency in Three Strikes sentencing “has been documented in a number of articles and at least one book.” (Ex. A at 13.) 5 Justice Rivera concluded: 5 See, e.g., Zimring et al., Punishment and Democracy/Three Strikes and You’re Out in California (2001), p. 119 (Zimring), there is an “extreme difference in punishment between third-strike felons who are sentenced under the terms of the law and the great majority of those eligible for thirdstrike sanctions who are not so prosecuted”; Note, A Swing and a Miss: California’s Three Strikes Law (1996) 17 Whittier L.Rev. 651, 687-688 [“The disparate application of the Law has the potential to lead to unjust results. If two defendants are convicted of the same crime in different counties, one may receive probation, while the other may receive a sentence of twenty-five years to life. This inconsistency is a result of a flawed version of the statute being enacted, therefore prohibiting the consistent application of the Law from county to county . . . .”]; Vitiello, Reforming Three Strikes’ Excesses (2004) 82 Wash. L.Q. 1, 21-22 [“Trial Courts and prosecutors are exercising their discretion in widely different ways around the state. That has led to county-by-county variations, which has resulted in ‘uneven justice,’ and undercut the law, which aimed for uniform treatment of defendants. Disparity derives from widely different attitudes towards the law in different counties across the state. Even if some discretionary regional differences are inevitable, in some parts of the state prosecutors are still using Three Strikes in questionable cases, ones in which punishment is likely to be excessive—that is, the amount of anticipated social protection does not justify the long terms of 9 The problem lies in the disparate treatment of the difficult case, such as the one before us. When a petty offense lands one defendant, with two property-crime strikes but no history of violence, in prison for 25 years to life, but another defendant with similar circumstances and a virtually identical criminal record is sentenced to a few years in prison or put on probation, we can expect a consequent cynicism and distrust toward the law and our criminal justice system. (Ex. A at 19.) This disparate treatment is a sign that Petitioner’s sentence is arbitrary and should be reversed. B. Ballot Materials As Well As The Statements of District Attorneys Throughout California Declare That Three Strikes Should Only Be Reserved For the “Worst Of The Worst.” Neither this Court nor any other court has ever defined the “spirit” of the Three Strikes law. In the absence of such decisions, courts should look to the ballot materials supporting passage of the law and publications by district attorneys throughout the state, who insist that harsh third strike punishment is reserved for the “worst of the worst.” (Paulson, Solano County District Attorney, From the Editor’s Desk (2007) 1 J. INST. FOR ADVANCEMENT CRIM. JUST. 4.) The ballot argument in favor of Proposition 184, which enacted the Three Strikes law in 1994, stated that the sentencing scheme was intended to keep “career criminals, who rape imprisonment imposed on some of the defendants currently incarcerated under the law.”]. 10 women, molest innocent children and commit murder, behind bars where they belong.” (Ballot Pamp., Gen. Elec. (Nov. 8, 1994), Argument in Favor of Prop. 184, p. 36.) District attorneys have taken a similar position. Solano County District Attorney David W. Paulson described the law as reserved for the “worst of the worst” offenders. (Paulson, supra, 1 J. INST. FOR ADVANCEMENT CRIM. JUST. 4.) Sacramento County District Attorney Jan Scully has described the law as “clos[ing] the revolving door on the most serious and violent repeat offenders.” (Scully, IACJ President’s Message (2007) 1 J. INST. FOR ADVANCEMENT CRIM. JUST. 2.) And Santa Clara County District Attorney George Kennedy described the law as allowing prosecutors to “remove demonstrably violent and dangerous repeat felons from among us . . . .” (Cal. District Attorneys Association, Prosecutors’ Perspective on California’s Three Strikes Law: A 10-Year Retrospective (2004), “Individual Perspectives,” p. v.) C. The Trial Court Below Abused Its Discretion Because Petitioner Falls at Least Partially Outside the “Spirit” of the Three Strikes Law Under Every Existing Definition. Here, the trial court abused its discretion when it sentenced Petitioner to a life sentence. A trial court must dismiss prior strike convictions while sentencing under Three Strikes when a defendant’s individual circumstances place him “outside the scheme’s spirit, in whole or in part.” (Williams, supra, 17 Cal.4th at p. 161 [citing Pen. Code § 1385; 11 People v. Superior Court (Romero) (1996) 13 Cal.4th 497].) Nothing before the trial court below suggested Petitioner was the kind of violent, predatory, and dangerous criminal the Three Strikes law was designed to permanently incapacitate. Instead, Petitioner’s abandonment of his prior criminal activities, acknowledged intelligence and human potential, and genuine prospects for long-term recovery through the support of friends, family, and the Delancy Street Residential Educational Center intensive drug treatment program demonstrate Petitioner’s exclusion from the spirit of the law. (CT 56-58, 166.) By ignoring these facts and instead relying entirely on Petitioner’s previous burglary convictions to justify its imposition of a life sentence, the sentencing court abused its discretion and the Court of Appeal erred in failing to reverse. (CT 41-43.) Indeed, Petitioner’s commitment offense is even less serious than the defendant who received relief in People v. Cluff (2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 991. In Cluff, the Court of Appeal held that a life sentence appeared “disproportionate by any measure” given the relatively minor nature of the defendant’s commitment offenses of failing to register as a sex offender. (Cluff, supra, 87 Cal.App.4th at p. 1004.) In contrast to Petitioner’s offense, Cluff’s failure to register as a sex offender was a mandatory felony, carrying a minimum prison term of 16 months and maximum of three years (absent enhancements). (Cluff, supra, 87 Cal.App.4th at p. 994; Pen. Code § 290(g)(2) [circa 1997]; see also Carmony, supra, 127 12 Cal.App.4th at p. 1066 (“[reversing a Three Strikes sentence where defendant failed to register as a sex offender after conviction for oral copulation by force or fear, or with a minor under age 14 and two subsequent convictions for assault with a deadly weapon”]; Ramirez, supra, 365 F.3d 755, 767-68 [reversing despite prior robbery strike involving use of a knife]; Banyard, supra, 342 F.Supp.2d 865, 873-74 [reversing despite prior convictions for robbery and assault with a deadly weapon.]) Based on this precedent, the sentencing court abused its discretion and the Court of Appeal erred in failing to reverse. II. PETITIONER’S SENTENCE IS CRUEL AND UNUSUAL AND REQUIRES REVERSAL UNDER BOTH THE STATE AND FEDERAL CONSTITUTION. As discussed above, this Court has never addressed the relationship the Three Strikes law and the state and federal bans on cruel and unusual punishment. Instead, this critical area of criminal jurisprudence has been left exclusively to the federal courts and one California Court of Appeal. Federal courts have invalidated sentences on Eighth Amendment grounds in Gonzalez, 551 F.3d 875, Ramirez, 365 F.3d 755, Banyard, 342 F. Supp. 2d 865, and Duran, 227 F. Supp. 2d 1121. A California Court of Appeal took similar action reversing a sentence on state and federal constitutional grounds in Carmony, supra, 127 Cal.App.4th 1066. Each of these cases involved a defendant with at more serious or violent instant offense or criminal history than Petitioner. The California Supreme should take this 13 opportunity to address the grounds on which a Three Strikes sentence violates the Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution in light of these major developments. A. This Court Has Never Analyzed The Three Strikes Law Under The Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution. The Court of Appeal asserted below that a Three Strikes sentence “will pass Eighth Amendment muster as long as it was correctly imposed pursuant to our state’s Penal Code.” (Ex. A at 9.) The error in the Court of Appeal’s logic is plain. The court below claims that any Three Strikes sentence “correctly imposed pursuant to [California’s] Penal Code” cannot violate the federal constitution. (Ex. A at 9.) If this were true, however, there would be no cases finding that a “correctly imposed” sentence violated the federal constitution. The United States Supreme Court and the Ninth Circuit have provided significant guidance in this area. Contrary to the Court of Appeals decision in this case, all of the Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit decisions directly addressing Three Strikes sentences have relied upon the three-factor analysis set forth in Solem v. Helm (1983) 463 U.S. 277. (See Ewing, supra, 538 U.S. 11; Gonzalez, supra, 551 F.3d 875; Ramirez, supra, 365 F.3d at p. 767-74; Banyard, supra, 342 F. Supp. 2d at p. 873-883; Duran, supra, 227 F. Supp. 2d at p. 1126-27.) These cases took as 14 mandatory 6 that a court must consider three “objective criteria” in determining whether a sentence is unconstitutionally disproportionate: (1) the gravity of the offense compared with the harshness of the penalty; (2) sentences imposed on other criminals in the same jurisdiction; and (3) sentences imposed for commission of the same crime in other jurisdictions. (Solem, supra, 463 U.S. at p. 292). In this case, all three criteria demonstrate that Petitioner’s sentence violates the Eighth Amendment: Petitioner’s offense is extremely minor; he is being punished more severely than rapists and murderers in California; and no other state would subject Petitioner to a life sentence for his crime. The Court of Appeal erred in failing to apply any meaningful analysis to Petitioner’s Eighth Amendment claim. Evaluated under the proper rubric, Petitioner’s sentence represents a “cruel and unusual” sentence in light of the federal test and the existing caselaw. 6 The Court of Appeal below contends that the federally mandated analysis became unnecessary after the Harmelin decision. (People v. Foroutan (Feb. 4, 2009, A118978), 2009 Cal. App. Unpub. LEXIS 976, *14n.6.) Importantly, all three Ninth Circuit courts construed the federal test set forth in Solem v. Helm (1983) 463 U.S. 277, as a mandatory analysis notwithstanding the fact that all four decisions issued after Harmelin. (See, e.g.., Duran, supra, 227 F. Supp. 2d at p. 1127 [holding that courts “must review penalties for gross disproportionality” and such a review is “guided by [the] objective factors” set out in Solem].) 15 B. This Court Has Never Analyzed The Three Strikes Law Under The California State Constitution Ban on Cruel and Unusual Punishment. This Court has never specifically considered the implications of the state ban on cruel or unusual punishment as it relates to Three Strikes sentences. In fact, the most recent non-capital sentencing guidance relevant to Three Strikes sentencing appears to be this Court’s decision in In re Lynch, 8 Cal.3d 410 (1972). In Lynch, this Court held that cruel or unusual punishment claims under the California Constitution should be evaluated according to (1) the seriousness of the instant offense; (2) the severity of the instant sentence compared to sentences for similarly severe crimes in the same jurisdiction; and (3) the severity of the sentence compared to what the sentence would be in other jurisdictions. Yet even this guidance has proved increasingly troublesome. Various California Courts of Appeal have reached conflicting conclusions on how to apply Lynch’s framework for assessing state cruel or unusual punishment claims. (Compare Carmony, supra, 127 Cal. App. 4th 1066 [reversing a Three Strikes sentence after comparing it the sentences for murder and rape in California]; with Romero, supra, 99 Cal.App.4th 1418 [upholding a Three Strikes sentence after refusing to compare it to the sentences for murder and rape in California].) This conflict and lack of controlling guidance has taken a particularly heavy toll in the context of Three Strikes sentencing. For 16 example, the court below erroneously held that that possession of any amount of drugs—no matter how minute—constitutes a sufficient threat to society to support a life sentence under the California constitution. To reach this conclusion, the court below relied upon Harmelin v. Michigan (1991) 501 U.S. 957. In Harmelin, the United States Supreme Court justified a life sentence for possession of illegal narcotics based on the deleterious social effects of drug use in the United States. (Harmelin, supra, 501 U.S. at p. 1002-1003) But in Harmelin, the Supreme Court directed its opinion at a defendant convicted for possessing 672 grams of cocaine—or 65,000 usable doses, according to the Court. (Id. at p. 1002.) Conversely, several federal courts have recognized that simple possession is not sufficiently serious to warrant a life sentence. (See Duran, 227 F. Supp. 2d at 1129 n.12 [simple possession of narcotics for personal use does not pose the “serious risk to society” discussed in Harmelin].) In short, California Courts of Appeal have no consistent standard for assessing seriousness—resulting in widely varying sentences for identical crimes throughout the various appellate districts discussed by Justice Rivera below. Addressing the application of the state ban on cruel or unusual punishment to Three Strikes sentences would help bring consistency to the sentencing process and clarify the proper method for assessing claims under the state ban on cruel or unusual punishment. 17 III. PUNISHING PETITIONER AGAIN FOR HIS BURGLARY PRIOR CONVICTIONS VIOLATES THE DUE PROCESS REQUIREMENTS SET FORTH IN THE FOURTEENTH AND FIFTH AMENDMENTS OF THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTION. A plain reading of the sentencing transcript reveals that the Superior Court imposed a life sentence in this case because of Petitioner’s prior burglary convictions rather than his instant offense. (RT 15-17.) Of course, Petitioner has already been punished for these crimes. Punishing Petitioner for these offenses again violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution and the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution. (See Banyard, supra, 342 F.Supp.2d at pp. 873-74 [“[t]o use a minor triggering offense simply to increase the punishment for prior offenses retroactively would violate fundamental principles of due process and double jeopardy.”].) CONCLUSION Petitioner respectfully requests that this Court exercise its discretion and grant review of these important legal issues. _______________________________ Michael S. Romano Attorney for Petitioner Ali Foroutan 18 WORD COUNT CERTIFICATION The text of this brief consists of 4,199 words as counted by the Microsoft Office Word 2004 word processing program used to generate the brief. Date: March 15, 2009 ____________________________ Michael S. Romano Attorney for Petitioner Ali Foroutan 19 PROOF OF SERVICE BY MAIL 1013(a), 2015.5 C.C.P. Re: People v. Ali Foroutan, Supreme Court No. ____________ I am a citizen of the United States; my business address is 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305. I am employed in the County of Santa Clara, California, where this mailing occurs; I am over the age of eighteen uears and not a party to the within cause. I served the within: Petition for Review On the following person(s) on the date set forth below, by placing a true copy thereof enclosed in a sealed envelope with postage thereon fully prepaid, in the United States Post Office mail box at Stanford, California, addressed as follows: Edmund Brown Office of the Attorney General 1300 “I” Stret P.O. Box 944255 Sacramento, CA 94244-2250 Marin County Superior Court Hon. John S. Graham Kim Turner, Court Executive Officer 3501 Civic Center Dr., Room #116 San Rafael, CA 94903 Court of Appeal, First District Division Four Clerk of Court 350 McAllister Street San Francisco, California 94102 Edward S. Berberian, Jr. District Attorney 3501 Civic Center Drive, Room 130 San Rafael, CA 94903 Ali Foroutan, T-75027 C1-108 P.O. Box 921 Centinela State Prison Imperial, CA 92251 Executed on March 15, 2009, at Stanford, California. ____________________________ Michael S. Romano 20