rotator cuff tendinitis - Newton Physical Therapy

advertisement

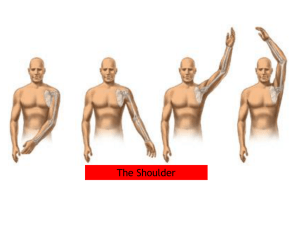

ROTATOR CUFF TENDINITIS Rotator Cuff tendinitis is one of the most common ailments in the human species. This is because our shoulders are the least stable joints in our bodies. In allowing for movement in 6 different planes of motion, the shoulder gives up the stability found in most other joints. In addition, the shoulder is composed of a ball and socket joint in which the head of the humerus sits in the glenoid labrum which acts as a socket. This socket is smaller than it should be enabling greater shoulder flexibility than any other joint as well as greater tendency for subluxations and dislocations. The head of the humerus sits in the glenoid labrum in a similar way that a golf ball sits on a tee. Tendinitis is a condition in which the muscle tendon is inflamed causing pain and is often accompanied by fluid. Tendinitis pain only occurs when the muscle tendon that is painful is active. Tendinitis is distinguished from bursitis which is a condition in which bursa (fluid) is inflamed and can occur whether or not the muscle is activated. Both tendinitis and bursitis represent common overuse syndromes. The Rotator Cuff is composed of four different tendons that serve to stabilize the shoulder when it is active. The tendons are the supraspinatous, infraspinatous, teres minor and subscapularis. The supraspinatous, infraspinatous, and teres minor primarily enable the shoulder to externally rotate which allows us to reach backwards and assists the motion of reaching overhead. The subscapularis is the primary internal rotator of the shoulder. Such an action is prominent when we reach behind our back to put on some article of clothing. The Rotator Cuff is located in a very crowded region of the body. In the same region, the long head of the biceps and the deltoid muscles can be found. The long head of the biceps acts independently of the Rotator Cuff but is often squeezed or impinged with trauma to the rotator cuff tendons, the acromion, the humerus, or the scapula. The deltoid acts in concert with the teres minor and infraspinatous for the motions of external rotation and abduction (moving the arm away from the body). In addition, the brachial plexus which is where all of the nerves of the arm muscles originate or pass through is in the same region. Any action involving moving the arm overhead with force is not a motion that the shoulder is made for handling. Thus throwing a ball, serving a tennis ball or passing a lacrosse ball all excessively strain the rotator cuff tendons by placing more force on these tendons than they are made to handle. The Rotator Cuff tendons can also be strained by repetitive overhead activity that involves a lower degree of force. People who work in jobs that require repetitive reaching up to shelves or reaching away from their bodies can also injure or tear one of the rotator cuff tendons. The most commonly ruptured Rotator Cuff tendon is the supraspinatous. This tendon, as all the Rotator Cuff tendons do, originates on the scapula. While the muscle belly of the supraspinatous sits on the superior portion of the scapula, its tendon extends to the anterior portion of the shoulder and attaches to greater tuberosity of the humerus. This tendon is frequently squeezed, strained or impinged with overhead activity. The greater the force or the frequency of such motion, the greater is the likelihood of causing an impingement to the supraspinatous tendon. An excessive impingement or strain will usually result in a tear of the tendon. The supraspinatous tendon is also the most commonly impinged tendon in the rotator cuff region. Impingement usually accompanies tendinitis. Any type of Rotator Cuff injury is painful and involves long recovery period. Rehabilitation following Rotator Cuff surgery for a torn tendon can easily last a year. Even recovering from a subluxed (displaced humeral head in a downward direction) can take six months of steady physical therapy. If an injury has occurred to your Rotator Cuff or other part of your shoulder, it is important to seek physical therapy in order to prevent a frozen shoulder. A frozen shoulder prevents you from being able to reach above shoulder height. This is because the necessary action of shoulder external rotation, which enables shoulder elevation above 90 degrees, cannot occur with a frozen shoulder. Extensive manual therapy combined with pain relief modalities and proper exercise instruction are essential following a Rotator Cuff surgery, strain or impingement to prevent permanent damage and regain normal function and shoulder mobility. Proper physical therapy for a Rotator Cuff injury such as an impingement or tendon tear involves pain relief modalities, manual stretching, myofascial release, and exercise instruction. Manual therapy needs to be tailored to each individual’s pain level, condition, and ability to begin exercise. Initial exercises focus on stretching. As pain subsides and motion is restored, the focus of therapy shifts to improving strength and scapula stability. Strengthening the Rotator Cuff tendons effectively improves scapula stability enabling pain free motion to occur with greater frequency thus restoring normal function. If you are currently experiencing any pain or discomfort in your shoulder, Newton Physical Therapy would be happy to evaluate your condition and recommend the best course of action. The shoulder is a complex and dynamic joint that requires proper care to function in all positions with varying degrees of force applied for whatever activity you may need your shoulder to perform.