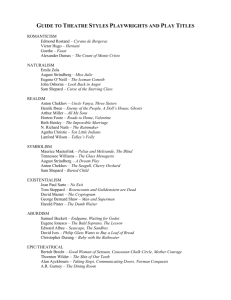

The Cherry Orchard: Complete Synthesis of Vision and

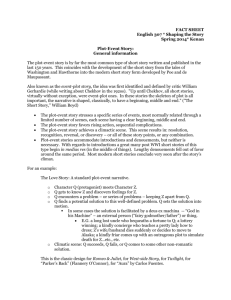

advertisement