The Emperors' Cloak: Aztec Pomp, Toltec

advertisement

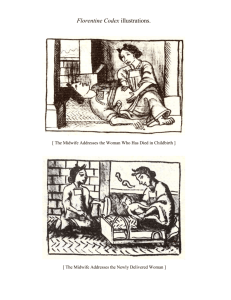

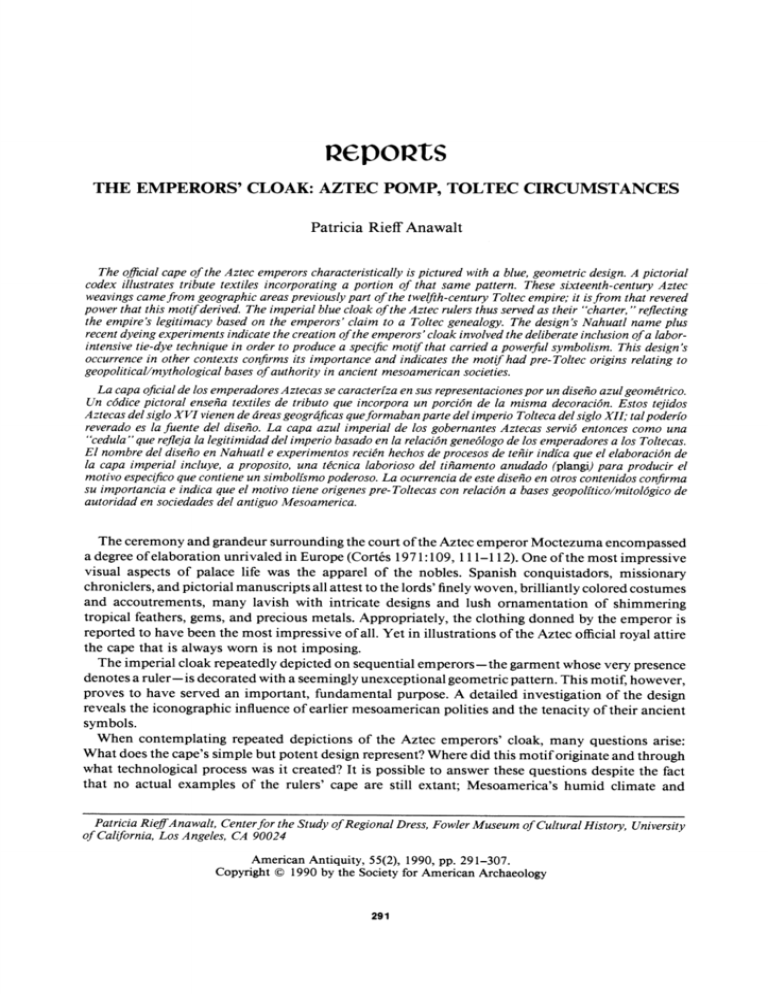

zepOptS THE EMPERORS' CLOAK: AZTEC POMP, TOLTEC CIRCUMSTANCES Patricia Rieff Anawalt The officialcape of the Aztec emperorscharacteristicallyis picturedwith a blue, geometricdesign.A pictorial codex illustratestributetextiles incorporatinga portion of that same pattern. These sixteenth-centuryAztec weavingscamefrom geographicareaspreviouslypart of the twelfth-centuryToltecempire;it isfrom that revered powerthat this motifderived.The imperialblue cloak of theAztec rulersthusservedas their "charter," reflecting the empire'slegitimacybased on the emperors'claim to a Toltecgenealogy. The design'sNahuatl name plus recentdyeingexperimentsindicatethe creationof the emperors'cloak involvedthe deliberateinclusionof a laborintensivetie-dye techniquein orderto producea specificmotif that carrieda powerfulsymbolism. This design's occurrencein other contexts confirmsits importanceand indicatesthe motif had pre-Toltecorigins relatingto geopolitical/mythologicalbases of authorityin ancient mesoamericansocieties. La capa oficialde los emperadoresAztecasse caracterizaen sus representaciones por un disenoazul geometrico. Un c6dicepictoral ensena textiles de tributoque incorporaun porci6n de la misma decoraci6n.Estos tejidos Aztecasdel siglo XVI vienende dreasgeogrdficasqueformabanpartedel imperioToltecadel siglo XII; talpoderfo reveradoes la fuente del diseno. La capa azul imperialde los gobernantesAztecas servi6 entoncescomo una "cedula"que reflejala legitimidaddel imperiobasadoen la relaci6ngene6logode los emperadoresa los Toltecas. El nombredel diseno en Nahuatl e experimentosrecienhechosde procesosde tenir indica que el elaboraci6nde la capa imperial incluye, a proposito,una tecnica laboriosodel tiniamentoanudado (plangi)para producirel motivoespecificoque contieneun simbolismopoderoso.La ocurrenciade este disenoen otroscontenidosconfirma su importanciae indica que el motivotiene origenespre-Toltecascon relaci6na basesgeopolftico/mitologicode autoridaden sociedadesdel antiguoMesoamerica. The ceremony and grandeur surrounding the court of the Aztec emperor Moctezuma encompassed a degree of elaboration unrivaled in Europe (Cortes 1971:109, 111-112). One of the most impressive visual aspects of palace life was the apparel of the nobles. Spanish conquistadors, missionary chroniclers, and pictorial manuscripts all attest to the lords' finely woven, brilliantly colored costumes and accoutrements, many lavish with intricate designs and lush ornamentation of shimmering tropical feathers, gems, and precious metals. Appropriately, the clothing donned by the emperor is reported to have been the most impressive of all. Yet in illustrations of the Aztec official royal attire the cape that is always worn is not imposing. The imperial cloak repeatedly depicted on sequential emperors-the garment whose very presence denotes a ruler-is decorated with a seemingly unexceptional geometric pattern. This motif, however, proves to have served an important, fundamental purpose. A detailed investigation of the design reveals the iconographic influence of earlier mesoamerican polities and the tenacity of their ancient symbols. When contemplating repeated depictions of the Aztec emperors' cloak, many questions arise: What does the cape's simple but potent design represent? Where did this motif originate and through what technological process was it created? It is possible to answer these questions despite the fact that no actual examples of the rulers' cape are still extant; Mesoamerica's humid climate and PatriciaRieffAnawalt,Centerforthe Studyof RegionalDress,FowlerMuseumof CulturalHistory,University of California,Los Angeles, CA 90024 AmericanAntiquity, 55(2), 1990, pp. 291-307. CopyrightC) 1990 by the Society for AmericanArchaeology 291 292 AMERICANA RE __ _.. . . ; _ ,; 7 < 0 Z t i'>||24*;-'rsb | | E ; f v f S f _ 0 0 *i _AF ' t 0 | d . . X \ >>0 b- '0 0 \ w iW ' ; f ' 0; A R : g . 0; 0 | X 0 ; F 0 , 0 ; 0 * f 0 f X, ; _ i ; -0-0< 0 :0 ' * ; 1 ,.L z *, t = SS!st c As?99l =Lee S6r alulF *W 294 AMERICANA "spa-' ' .*-'a' N 3? :: \ fI3* - \' *5 a - , , 0 0 RE 1* ' 3? a ' t , ,. 4' . .-v. . AMERICAN 296 , 4 REP (4) # 4 tt r j 298 ANTIQUITY AMERICAN [Vol. 55, No. 2, 1990] (de Sahagun 1950-1982:l:Plate 41, 1979:1:Folio 39v). Fortunately the friar provides the name of the design on Yacatecuhtli's cloak: xiuhtlalpilli (de Sahagun 1950-1982:1:44). In another context, when discussing the apparel of the twelfth-century Toltecs, de Sahagun relates, "[The Toltecs'] clothing was-indeed their privilege was-the blue knotted cape [xiuhtlalpilli]" (de Sahagiin 1950-1982:10:169). This statement, together with the analysis of the tribute-textile ideograms discussed earlier, strongly supports the contention that the Aztec rulers' official cloak served as their "charter," reflecting the empire's legitimacy based on the emperors' claim to a Toltec genealogy. THE TECHNOLOGICAL CLUES INHERENT IN THE DESIGN MOTIF'S NAME A careful examination of the design motif on the emperors' cloak raised the question of how it might be reproduced. The etymology of its Nahuatl name provided the technological information needed to proceed. Fray Alonso de Molina, in his 1572 Spanish and Nahuatl dictionary, defines xihuitl as blue-green ("turquesa") (de Molina 1977:159v), and tlalpilli as something tied, or knotted ("cosa atada, o ahudada") (de Molina 1977:124v). With these definitions, Molina not only provides clues as to the type of dye used to create the rulers' cape but, even more importantly, the manner in which it was applied. The Nahuatl term tlalpilli indicates a dyeing process that involves the tieing/knotting off of a portion of cloth so that the resulting reserved section cannot absorb the dye. This resist-dye technique is known commonly by its Indonesian name, plangi. De Sahagun makes repeated references to tlalpilli-created designs. In the total corpus of his work, he provides over 400 textile-motif names, most of which appear only once or twice. Designs created using the tlalpilli technique, however, are referred to at least 33 times. In addition to the blue xiuhtlalpilli garments-worn only by deities and rulers-there also are repeated references to clothing with quappachtlalpilli (tawny) and colotlalpilli (scorpion [a gray-orange?]) motifs (Anawalt 1988-1989). The xihuitl (turquoise [i.e., blue-green]) element in the cloak's name implies the use of indigo, a blue dye known to have been employed in Prehispanic Mesoamerica. It is referred to by de Sahaguin (1950-1982:8:47-48, 10:91-92) and fragments of indigo-dyed cloth have been found archaeologically (Mastache de Escobar 1974). There are several symbolic implications to the choice of blue as the color for the emperors' cloak. The word xihuitl, in addition to translating "precious turquoise stone," can by extension also refer to other objects of great value. In addition, the term refers to the hue blue-green, the quintessential Toltec color (de Sahaguin 1950-1982:10:169). Returning to the problem of re-creating the blue diaper motif, it quickly became apparent that what was needed first was a carefully detailed depiction of such a pattern. Most drawings of the emperors' cloak are too highly stylized to be of help (see Figure 6), but Codex Ixtlilxochitl contains an ideal example. The royal raiment of King Nezahualpilli,' ruler of Texcoco-one of the three city-states that controlled the Aztec empire-proved an excellent model both for its clarity and the arrangement of the small, repeated elements of the diaper motif into a revelatory pattern (Figure 7). The repeating geometric design on Nezahualpilli's cape is formed by two interlocking step frets, one composed of squares containing dots and the other of dot-encasing diamonds. Guided by the Nahuatl name of the emperors' cloak, the initial attempt to re-create the pattern involved dyeing cloth with indigo using the plangi tieing technique. The result was disconcerting. Because of the propensity of woven cloth to stretch when pulled on the bias, it proved impossibleusing only the plangi method-to create both squares and diamonds in such close configuration. No matter how the reserved sections were manipulated, only diamonds running along the warp and weft of the material would emerge (Figure 8). Still convinced that the term xiuhtlalpilli held the key to the technology used to create the rulers' cape, I consulted two artists sophisticated in dyeing techniques: Virginia Davis of New York and Pamela Scheinman of New Jersey. REP 4 300 AMERICA RE / rJ J\LYJ 'p 2 / " 302 AMERICA REP 304 AMERICAN RE t A 306 AMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 55, No. 2, 1990] The custom of bestowing textiles as gifts was not limited to only the residents of the capital. Visitors were similarly honored, and the weavings they received were both plentiful and of great value. The Florentine Codex makes reference to such gifts as "costly capes" (de Sahaguin 19501982:8:52) and "capes without price" (de Sahagun 1950-1982:8:64-65). Particularly germane to the concerns of this paper is de Sahagun's report that a newly installed ruler distributed bundles of such weavings among visiting lords, presenting them with "the precious capes, appropriate to them, the ones to which they were entitled" (de Sahaguin 1950-1982:4:88-89). Obviously, at least some of the cloaks given as gifts were lineage and/or area specific. Nor were all of the recipients of such textiles allies. De Sahaguin states that the emperor gave appropriately decorated capes to "the lords from everywhere-friends of the ruler, and all the lords unfriendly to him" (de Sahagun 1950-1982:8:44). Among the latter category of visiting dignitaries are listed nobles from Tlaxcala, Cholula and Huexotzinco (de Sahagun 1950-1982:8:65). Although each of these polities was a long-time adversary of the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, the lords from those unfriendly areas were all Chichimec/Toltec descended. As a result, these wary guests would have shared the high-born Aztecs' appreciation and privilege of wearing textiles bearing a section of the blue diaper motif, heraldic emblem of royal Toltec descent. The above investigation of the blue diaper motif demonstrates the power of a method of cultural reconstruction based on depictions of Prehispanic weavings. This textile-focused approach is enriched by using evidence from several media produced by different artists of varying backgrounds. From such a data base, new understanding of long-familiar images emerges. Perhaps even more important, unexpected insights are gained into the functioning of ancient societies, the nature of past political divisions, and the tenacious continuity of prestige symbols handed down from earlier civilizations. In the case of the Aztec emperors' cloak, analysis of its decorative design provides new understanding of the geopolitical/mythological bases of authority in ancient Mesoamerica. Acknowledgments. Duringthis paper'sevolution, the followingcolleagues'assistanceand comments have been most gratefullyreceived:ClemencyCoggins,GeorgeCowgill,ChristopherDonnan,AlanGrinnell,Wolfgang Haberland,Norman Hammond,Doris Heyden, Eloise QuifionesKeber,WalterF. Morris,Jr., H. B. Nicholson, 0. J. Polaco R., and MarcThouvenot.Jean Sells drewthe maps. The initialplangi dyeingexperimentwas done by Penny Olson, Art Department,University of California,Los Angeles. I am beholden to VirginiaDavis of New York City and Pamela Scheinmanof HighlandPark,New Jersey,for their aid in re-creatingthe pattern on King Nezahualpilli'scloak. REFERENCES CITED Anawalt, P. R. 1988-1989 Aztec Clothing Styles and Design Motifs. Ms. in possession of author. Barlow, R. H. 1949 The Extent of the Empire of the Culhua-Mexica. Ibero-Americana 28. University of California Press, Berkeley. Berden, F. F. 1980 The Matricula de Tributos-Provincial Tribute. In Matricula de Tributos, edited by F. F. Berdan and J. de Durand-Forest, pp. 27-43. Akademische Druck-und Verlagsanstalt,, Graz, Austria. Boone, E. H. (editor) 1987 The Aztec Templo Mayor. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. CodexBorbonicus 1974 Codex Borbonicus. Edited by K. A. Nowotny and J. de Durand-Forest. Akademische Druck-und Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria. CodexDresden 1975 Codex Dresdensis. Edited by H. Deckert and F. Anders. Akademische Druck-und Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria. CodexIxtlilxochitl 1976 Codex Ixtlilxochitl. Edited by J. de Durand-Forest. Akademische Druck-und Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria. CodexMendoza 1938 Codex Mendoza. 3 vols. Edited by J. C. Clark. Waterlow & Sons, London. 1991 Codex Mendoza. 3 vols. Edited by F. F. Berdan and P. R. Anawalt. University of California Press, Berkeley, in press. REPORTS 307 Coggins, C. 1987 Quetzalcoatl and the Classic Maya. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, Chicago. Cort6s, H. 1971 Hernan Corte6s:Letters from Mexico. Translated and edited by A. R. Pagden. Grossman, New York. Davies, N. 1982 The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico. Allen Lane, London. de Molina, A. 1977 Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana, y mexicana y castellana. Editorial Porruia,Mexico City. de Sahaguin, F. B. 1950-1982 Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Translated and edited by A. J. 0. Anderson and C. E. Dibble. Monographs of the School of American Research No. 14, pts. 2-13. University of Utah, Salt Lake City and School of American Research, Santa Fe. 1979 C6dice Florentino. 3 vols. Guinti Barb6ra, Florence. Johnson, I. W. 1989 Antiguo Manto de Plum6n de San Miguel Zinacantepec, Estado de M6xico, y otros tejidos emplumados de la 6poca colonial. In Enqu&tes sur L'Amerique Moyenne: Melanges offerts d Guy Stresser-Pean, edited by D. Michelet, pp. 163-183. Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Consejo Nacional Para La Cultura y Las Artes and Centre D'Etudes Mexicaines et Centram6ricaines, Mexico. Mastache de Escobar, A. G. 1974 Dos Fragmentos de Tejido Decorados con la Tecnica de Plangi. Anales del Instituto Nacional de Antropolgia e Historia, Epoca 7a, Tomo IV:251-262. Mexico. Nicholson, H. B. 1988 The Provenience of the Codex Borbonicus: An Hypothesis. In Smoke and Mist: Mesoamerican Studies in Memory of Thelma D. Sullivan, edited by J. K. Josserand and K. Dakin, pp. 77-97. BAR International Series 402. British Archaeological Reports, Oxford. Pasztory, E. 1983 Aztec Art. Harry N. Abrams, New York. Primeros Memoriales 1926 [1905] Illustrations to Primeros Memoriales. In Historia de las Cosas de Nueva Espana por Fr. Bernardino de Sahagun, vol. V, edited by F. del Paso y Troncoso. Talleres Graficos del Museo Nacional de Arquelogia, Historia y Ethnografia, Mexico. Schele, L., and M. E. Miller 1986 The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth. Sharp, R. 1981 Chacs and Chiefs: The Iconology of Mosaic Stone Sculpture in Pre-Conquest Yucatan. Studies in PreColumbian Art and Archaeology Series No. 24. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. Thompson, J. E. S. 1966 Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: An Introduction. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. 1970 Maya History and Religion. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. NOTE ' For information on the technique used to create the border pattern on King Nezahualpilli's cloak see Johnson 1989. Received July 16, 1989; accepted September 12, 1989