A Comprehensive Phylogeny of the Bumble Bees (Bombus)

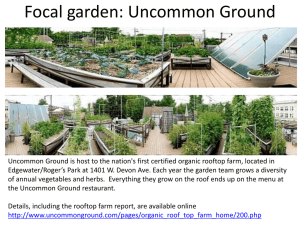

advertisement