Transcript of the Conference - Couchiching Institute on Public Affairs

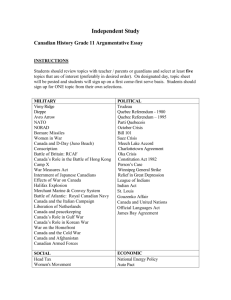

advertisement