Product Cannibalism - Southern Methodist University

advertisement

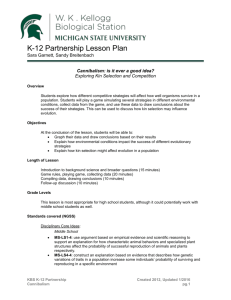

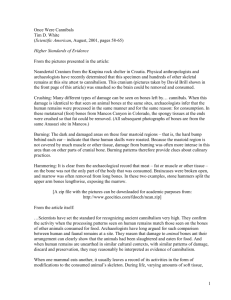

CHAPTER 48 PRODUCT C A N N I B A L I S M Roger A. Kerin, PhD Harold C. Simmons Distinguished Professor ofMarketing Edwin L. Cox School of Business Southern Methodist University Dallas. Texas Dwight R. Riskey, PhD Vice President, Marketing Research and New Business Frjto-Lay, Inc. Piano, Texas Slowed economic growth, compressed product life cycles, domestic and foreign competition, and consumer desire for variety have placed unprecedented pressures on product management. Properly or improperly, many firms appear to be focusing their efforts on product opportunities that offer minimal market resistance, leverage existing technologies, utilize present manufacturing capability and capacity, and minimize financial investment. These opportunities are often manifested in product line extensions. It is estimated that 81 percent of new consumer products are extensions of existing products. No product category seems to be immune from the surfeit of product offshoots. In 1990 alone, product line extensions included 64 different sauces, 103 snack chips, 91 cold remedies, and 69 disposable diapers.1 Line extensions are routinely achieved in a number of ways.2 Introduction of new sizes (super economy-size toothpaste), forms (deodorant in liquid, powder, spray, and stick forms), compositions (regular Head & Shoulders, shampoo and Head & Shoulders shampoo with conditioner), flavors (Jello gelatin, which originally began with six flavors, is now available in more than a dozen), packages (Hi-C fruit flavored drink in glass bottles or paper or metal containers), and varieties (shampoo for dry, normal, and oily hair) are just some of the feasible courses of action. In general, dominant firms in a product category or industry tend to view product line extension as a relatively low risk means of maintaining or increasing market share, and as an indispensable tool in the fierce struggle for retail shelf space. For example, an Association of National Advertisers study indicated that the majority of line extensions were considered successful. By comparison, only about one-half of new products were deemed successful.3 On the other hand, low market share firms and potential new entrants tend to view the line extension strategies of dominant firms as a calculated strategy to corner supermarket shelf space, keep out rival brands, and protect their competitive position. Even though product-line extension strategies pose minimal risk of failure for the product being introduced, potential negative effects on existing products serving existing markets must be considered. These effects can be called product .cannibalism. While some cannibalism may be planned or expected, considerable amounts of cannibalism may be an unexpected consequence of an improperly managed product development process and line extension program. When AnheuserBusch launched Michelob Light, it fully expected that 20-25 percent of the new brand would come from its existing base brand because of its low-calorie appeal among current customers.4 However, despite PRODUCT CANNIBALISM MARKETING MANAGER'S HANDBOOK numerous efforts to differentiate and position Stouffer Food Corporation's Right Course frozen entree, the brand cannibalized the company's popular Lean Cuisine brand. Six months after the introduction of Right Course, it was pulled because, according to a company official, "This brand [Right Course] ended up competing with our Lean Cuisine line." The purpose of this chapter is to examine several different facets of product cannibalism. We begin by describing the dynamics underlying product cannibalism. Managerial practices and competitive conditions that foster cannibalism are then enumerated. Because cannibalism is sometimes justified on the basis of competitive reality, the strategy of preemptive cannibalism is introduced. The financial consequences of product cannibalism are then illustrated from the perspective of individual products and product line profitability, and approaches for identifying cannibalism potential are briefly described. The chapter concludes with a discussion on the implications of product cannibalism for product line management. NATURE OF PRODUCT CANNIBALISM The theoretical roots of product cannibalism can be traced to the .theory of cross-elasticity of demand. This theory suggests that the percentage change in the quantity of product A demanded will be influenced by the percentage change in the price of product B. The "demand interrelationship between two products may be described as complementary or substitutable. For example, if the price of product B decreases and the quantity demanded of product A increases, the two products are considered to be complements, providing other things remain equal. Common examples illustrating complementary products are razors and razor blades and cameras, and photographic accessories. In the case of product substitution, or cannibalism, a lowering of the price on product A will tend to decrease the quantity demanded for product B, providing other things remain equal. Margarine is sometimes viewed as a substitute for butter. From a marketing standpoint, however, other things rarely remain equal. Accordingly, an expanded interpretation of cross-elasticity of demand is necessary. In addition to price changes, physical and symbolic attributes of products, alternative means of promoting and distributing products, and potential end-use interchangeability between products must be considered. In addition, attention must be given to the potential for variety-seeking by consumers. That is, for some product categories (e.g., snack foods and soft drinks) consumers tend to purchase and consume multiple flavors and sizes. As shown in Exhibit 1, new entrants and line extensions acquire their sales revenue from three sources: (1) new consumers who were not previously buyers of the product type; (2) consumers of competitive brands within a product category; and (3) consumers of an existing EXHIBIT 1. Components of New Entrant Sales Revenue Revenue Source Revenue Type Market Expansion and Market Share Gains Incremental Revenue New Entrant Sales Revenue Product/Brand Switching within the Product Line Redistributed Revenue company brand or product who switch to the new entry. The first two sales revenue sources represent, respectively, incremental revenue for the product line because of market expansion and the capturing of competitors' market share or share-building. The remaining sales revenue source represents redistributed revenue, or cannibalization, in that existing buyers are substituting one item for another in the company's product line. Accordingly, product cannibalization can be succinctly defined as the process by which a firm's new entry gains a portion of its sales by diverting them from a firm's existing product(s). This process of sales diversion or redistribution of revenue has a subtle but managerially important consequence. Assuming that the change in profits earned by the existing product is reduced or negative because of substitution, this amount should be added to the incremental cost curve for the new offering. The implication is clear—sales and profit gains of a new entry at the expense of an existing product do not filter down to the bottom line. Rather, the loss of potential profits from a cannibalized product is real cost that must be absorbed by the new product. The adage "You can't have your cake and eat it, too" applies when cannibalism occurs. 883 MARKETING MANAGER'S HANDBOOK As a generalization, it has been suggested that a product-line extension must gain two market share points for each share point lost by cannibalized products to preserve profit margins. One-half of the gain will come from users of competitors' products and one-half from new users drawn into the category. Therefore, sales revenue for a product-line extension is divided equally among incremental sales volume, cannibalized revenue, and market share gains.6 FOSTERING CANNIBALISM The erosion of an existing product's share of market resulting from cannibalism may stem from,management decisions, or it may be a necessary evil, given competitive conditions. Cannibalism becomes a severe problem when it provides no incremental competitive or financial benefit to the firm's product line. Several managerial decisions appear to foster cannibalism of an existing brand's sales volume: 1. management pressure for sales growth from new offerings without full consideration of financial consequences; 2. preoccupation with developing a full line of products in an attempt to achieve increases in overall market share in a product class or category; 3. inadequate positioning of new entries resulting in their seeking the identity of existing products; 4. unrealistic or excessive market segmentation resulting in "two segments" with demands for identical product attributes or end-use needs; and 5. aggressive promotional effort or incentives reflected in sales representatives' overemphasis on new items and neglect of existing products. j- Product cannibalism by itself should not be viewed only negatively. Cannibalism sometimes represents an outgrowth of effective and competitive product management. For example, some firms might actively pursue line extensions for the purpose of building a base brand's "brand equity." This rationale has been used by some soft drink producers to justify cannibalism of regular soft drinks by diet and caffeine-free varieties. Even though diet and caffeine-free beverages divert sales from regular drinks, the equity of the base brand name is believed to be enhanced even though cannibalism among line items is present. Additionally, a new item with cannibalism potential may be introduced to eliminate gaps in a product line that might be filled by competing offerings or to neutralize competitive inroads. In other words, it may be wiser to have buyers switching among products and brands within a firm's product line than to have them switching out and purchasing competitive offerings. Viewed in this manner, preemptive cannibalism becomes a viable business strategy. 884 PRODUCT CANNIBALISM Preemptive cannibalism is the conscious practice of stealing sales from a company's existing products and brands to keep consumers from switching to competitors' offerings. Two product-line extension strategies are commonly employed in this regard: a flanker brand strategy and a fighting brand strategy. Flanker Brand Strategy Bristol-Meyers' introduction of Datril to compete with McNeil Laboratories' Tylenol exemplifies a flanker brand strategy. BristolMeyers held a position of strength in the aspirin segment of the analgesic market with its Bufferin and Excedrin brands. However, this segment, while large, had plateaued in the mid-1970s. During the same period, the acetaminophen (noninflammatory compounds) segment of the analgesic market dominated by McNeil Laboratories had grown substantially, with a portion of the growth coming from former and potential aspirin users. Datril's introduction would hopefully attract aspirin switchers (that is, switching away from company brands) and tap existing and potential acetaminophen buyers who would most likely purchase Tylenol. Therefore, even though Datril might cannibalize Excedrin and Bufferin, aspirin switchers would remain in the BristolMeyers analgesic product line rather than being attracted to Tylenol. A similar strategy was recently employed by the Miller Brewing Company with the introduction of Lite Genuine Draft, an extension of Miller's Genuine Draft beer. The company intended to have Lite Genuine Draft compete against Coors Lite and Budweiser Light in the premium segment of the light beer category since Miller Brewing believed Miller Lite users were switching to Coors and Budweiser brands. Even though it was likely that Lite Genuine Draft would steal sales from Miller's Genuine Draft and also Miller Lite, Leonard Goldman, president of Miller Brewing Company said: Miller Lite represents a tremendous presence in the fastest growing segment (light beer), but we are committed to having multiple brands in each segment to give the consumer the broadest array of choices. This is a fancy way of saying that if the consumer is going to defect, we want him to defect to another Miller product. "7 Fighting Brand Strategy A fighting brand is typically introduced when (1) a firm has a high relative share in a product category; (2) its dominant brands are susceptible to having share sliced away by aggressive pricing by smaller competitors; and (3) it wishes to preserve its profit margins on existing brands. The introduction of Santitas® brand Tortilla Chips by Frito-Lay illustrates a fighting brand strategy. As the tortilla chip category leader, managers for Tostitos® brand Tortilla Chips recognized the emergence of restaurant-style tortilla chips (RSTC) as a competitive threat in certain regional markets. Unflavored and typically priced below national and regional tortilla chip brands, RSTC were also lower in quality based on consumer taste tests. Nevertheless, lower pricing coupled with their primary use for dipping with sauces and nacho preparation resulted in RSTC capturing a sizable portion of tortilla chip volume. Frito-Lay introduced Santitas® brand Tortilla Chips at a competitive RSTC price and provided trade promotion to support the brand. This action, while cannibalizing a portion of Tostitos® brand Tortilla Chips, resulted in incremental volume growth and category share-building for Frito-Lay. ACCOUNTING FOR PRODUCT CANNIBALISM The previous discussion illustrates the importance of performing a marginal analysis on the new item in the product line within the context of present and forecasted market conditions. Incremental revenue, cost, and investment must be considered. An analysis of a hypothetical multiproduct firm serves to demonstrate the financial consequences of product cannibalism. This firm has an existing product that was expected to capture 5 percent of a market forecasted at 15 million units, or 750,000 units. At a $2.00 per unit price and a $1.00 per unit gross margin, forecasted sales are $1.5 million with a $750,000 gross margin. Budgeted marketing expenditures plus allocated overhead total $300,000, which will provide a $450,000 profit before taxes and a 10 percent return on investment. An abbreviated pro forma income statement showing these figures is shown in part A of Exhibit 2. A new offering is introduced that satisfies several, but not all, buyer requirements met by the existing product in addition to providing several other benefits. The new item is value-priced at $1.50 per unit with a $0.75 per unit gross margin. The lower price and modified product benefits are expected to expand the market for this product type by 20 percent to 18 million units. Both products combined are expected to capture 10 percent of the expanded market, or 1.8 million units, which represents a 240 percent increase over forecasted volume for the single existing product! Marketing expenditures plus allocated overhead for the new product are budgeted at $450,000. Incremental investment for the new offering is $1 million. Most of the volume captured by the new product comes from market expansion because of the lower price and differentiated product benefit structure. However, slightly more than 25 percent cannibalism rate occurs from the existing product. Part B in Exhibit 2 shows the effects of the activities and events described for the existing product and the new item, individually and combined. Also shown is an incremental analysis comparing the existing product alone versus the existing and the new product combined. Given the conditions of the example cited, the apparent new item 886 S „ 1 II O. 88 K CO CN rx O co 10 -« K £* 5? — "-o "l< v» K v> Is. < 8 88 O» •— CM CO 8 CO I O. • £888 8 8 8: f O Q *O O O O IO O s s »»„- 8 fi» O *O s 888: ~8' "1141« iisilL.lii 2O 1/1 _S "" ~Z £ F T! § MARKETING MANAGER'S HANDBOOK profit is much less when cannibalized volume is subtracted from the existing product's contribution. The apparent return on investment for the product line with the new offering is inflated; it is actually less than the return on investment for the existing product when cannibalized volume is taken into account. Finally, the incremental analysis reveals that the incremental profit from the new entry is only 30 percent of what it appears to be without consideration of cannibalism's affects. This example highlights several possible ramifications of product cannibalism: 1. Without accounting for product cannibalism, sales volume and profits for a new item may be more illusionary than real. 2. New-entries examined in an isolated fashion—without also considering cannibalized volume—provides a distorted view of productline profits and return on investment. 3. Market share growth for a product line resulting from a new entry may represent Pyrrhic victories in terms of product-line profitability and individual item volume. 4. Both the amount and source of potential new item volume must be considered in product-line planning to calculate the impact of 1 cannibalism on product-line profitability. Effects of Preemptive Cannibalism This analysis can also be used to illustrate the potential effects of preemptive cannibalism. Suppose in our hypothetical situation dial the new item described was used as a retaliatory device (fighting brand) to meet a competitor whose lower-priced product was capturing a portion of the existing product's market share. If one considers the new item's cannibalized volume as potentially lost to the competitor, then these buyer> are being kept by the firm, albeit at a lower rate of return. If the new item were not introduced, 200,000 units would be lost, resulting in a five percent return on the existing product's investment. Even with cannibalism considered, the firm's new product will virtually preserve the return on investment percentage, thus showing the benefit of preemptive cannibalism. Incremental Analysis It is also possible to calculate the incremental unit volume necessary to overcome the effects of cannibalism. This measure can be used as a benchmark for evaluating market capacity and the quality of introductory marketing programs early in the business analysis stage. The expression is as follows: Incremental volume Ratio of the to offset : Cannibalized x old and new unit volume cannibalism effect product margins 888 Using figures from the hypothetical example, the incremental volume necessary to overcome the effects of cannibalism is approximately 267,000 units: (200,000 units) x ($1.00 margin/$0.75 margin). In other words, at the estimated cannibalism rate, the new item must generate an incremental volume from new and competitors' customers of 267,000 units to offset the loss of margin dollars from the existing product. In effect, for this illustration, a 21 percent increase in incremental volume over forecasted levels would be required. Issues surrounding market capacity and the quality of the market entry program assume a different light in this context. In some instances, the dollar gross margin of the new item might exceed the dollar gross margin of the existing product that it cannibalizes. In this instance, for each unit of the existing product that is cannibalized, the firm records a higher dollar gross margin. Therefore, the firm would benefit from product cannibalism. It should be emphasized, however, that the incremental costs associated with advertising and promotion or any additions in manufacturing capacity costs must be considered to determine the net effect of cannibalism. If these incremental costs exceed the incremental benefits of higher dollar gross margin, then product-line profitability will suffer. IDENTIFYING CANNIBALISM POTENTIAL The importance of identifying cannibalism potential cannot be overemphasized. Cannibalism effects should be considered in light of product-market structure and throughout the product development process, beginning with concept testing and continuing through commercialization. Analysis of Product-Market Structure \ . Conventional approaches for defining product-market structure focuses on product segmentation. Exhibit 3 illustrates this approach for chip and vegetable dips sold through supermarkets. As shown, dips divide into two distinct categories. Prepared dips are ready-made and divided into two categories: (1) refrigerated dips such as Marie's and (2) shelf-stable dips such as Frito-Lay's Dips® which are sold in metal cans and require no refrigeration. Dip bases, which require at-home preparation, also divide into two categories: (1) dry soup mixes and (2) dry dip mixes. The implication of this structure is that prepared dips (refrigerated and shelf-stable) compete with each other, but not with dip bases. However, this conclusion might be incorrect when usage situations are considered. Recent research suggests that attention to usage context offers a broadened perspective on how consumers view. products and their substitutability, hence cannibalism potential. The substitution-in-use approach (SIU) simultaneously examines products and their usages to 889 MARKETING MANAGER'S HANDBOOK EXHIBIT 3. Product Segmentation of Vegetable and Chip Dips Sold Through Supermarkets reveal product-market structure. A key assumption underlying this approach is that products represent "benefit bundles" and when grouped on the basis of appropriateness for similar usages are presumed to deliver similar benefit combinations. The SIU approach implies that products perceived to be similar by consumers are considered substitutable as a means for the same ends or usages. Therefore, prepared refrigerated dips could be substitutes for dry dip mixes prepared at home for specific usage situations, e.g., parties. Accordingly, a dry dip mix line extension by a refrigerated dip producer could cannibalize the firm's existing product(s), at least for specific usage contexts. Applications of the SIU approach result in maps, dendrograms, and other visual depictions that attempt to portray product-market structure in a manner corresponding to consumers' mental representations of a product category (e.g., vegetable and chip dips). The mechanics of this approach are beyond the scope of this discussion.8 Nevertheless, by directing managerial attention toward consumer perceptions of products as a means to achieving an end inherent in a usage context, the SIU approach provides useful insights into product-market structure, product similarities, and product substitution potential. 890 PRODUCT CANNIBALISM Analysis of Product Features, Preferences, and Perceptions Substitution-in-use analysis offers a useful, although coarse-grain assessment of product comparability in usage contexts. This approach has a "black-box" character in that it does not measure directly the product features sought in a specific usage context nor consumer perceptions of the benefits afforded by individual products. Conjoint analysis is typically employed to study the linkage of product features to preferences and the linkage of features to consumer perceptions. This analysis technique is of special value in concept testing where its application is most prevalent.9 Conjoint analysis, which actually represents a family of multiattribute choice models, concerns itself with measuring the joint effect of two or more independent variables (e.g., product features) on the ordering of a dependent variable (e.g., preference). Conjoint analysis makes it possible to take a consumer's overall evaluation of a set of concepts and decompose those evaluations into separate scores—utility functions—for the various attributes or features of concepts that led to the consumer evaluating them the way he/she did. Consumer choices based on their individual utility functions can result in estimated share of choices and brand-switching matrices showing the (company or competitive) brands from which any of a number of new concepts (i.e., line extensions) can draw customers. For example, Sunbeam Appliance Corporation routinely uses conjoint analysis to assess new model concepts for its small appliance line both in terms of draw from competitive brands (e.g., Sears, Cuisinart) as well as cannibalization of its own models.10 Conjoint analysis also can be used as a tool for product positioning within a product line. For example, applications are possible that can provide insight into the value of a brand name (when brand names 1 are treated as independent variables) as well as the appropriateness of various brands for providing certain types of features and benefits. The latter application treats brands as dependent variables and combinations of product features are sorted according to their similarity to or appropriateness for various brands. An extended description of the statistical properties and application of conjoint analysis is beyond the scope of this discussion.11 Nevertheless, it is worth noting that as a concept-testing practice, conjoint analysis does show promise in its ability to predict actual consumer choice and produce valid market share estimates for new concepts.12 Since actual product sales and market share are often confounded by marketing mix variables such as advertising and distribution and competitive behavior, conjoint analysis as a predictive technique for assessing sources of volume for line extensions—hence, product cannibalism—is not a substitute for pretest market modeling and actual field market tests. PRODUCT CANNIBALISM Pretest Market Modeling and Field Test Marketing Cannibalism potential can be further identified and possibly refined beyond the concept-testing stage. As product ideas evolve from concepts to prototypes, segmentation and positioning strategies become clearer, introductory marketing programs can be drafted, and spending levels can be finalized. At this time, cannibalism potential can be assessed within the context of pretest market models. Pretest market models combine executive judgment on marketing strategy, historical data, laboratory data using product preference, and trial and repeat purchase models of buyer behavior to make sales and market share projections for new concepts.13 Most notably, pretest market models typically incorporate cannibalization estimates that are often based on data gathered from simulated market tests (or laboratory test markets) and preference modeling (e.g., conjoint analysis). Despite the benefits of pretest market models, they are not without limitations. Their application is limited to studying new brands seeking to enter well-defined product categories. They are not particularly suitable for products with long purchase cycles or products whose benefits are not immediately realized. Consequently, primary use of these models exists in evaluating consumer package goods and food products.. Furthermore, these models are limited to the analysis of individual products; they do not provide information on product line dynamics per se. Estimating a new offering's sales volume potential and its tendency to cannibalize existing products can be finally assessed by field test markets. Test markets allow product sales and product item interactions to be observed in an actual—although not always representative—competitive setting. Even in a test market setting, however, assessing cannibalism is not a trivial exercise. Although it is possible to perform product-by-product sales trend analysis to infer levels of cannibalism, trend analysis only uncovers cannibalism effects when they are large. Even then, alternative explanations for an existing product's sales decline can be invoked. The advent of controlled (scanner) test markets for consumer package goods sold using household panels offers considerable promise in assessing the sources and magnitude of product cannibalism. For example, algorithms for studying household panel data have been developed for analyzing a household's history of purchases before and after the introduction of a new item. These algorithms have proven useful in studying sources of volume for existing products and line extensions. Analysis of household panel data reveals that cannibalism rates ranging from 60 to 70 percent are common for minor line extensions to 10 to 20 percent or less for new offerings with significant, previously unaddressed consumer benefits. A new flavor of potato chip, for instance, typically generates 50 percent incremental volume for its 892 base brand. An altogether new and unique snack chip brand may produce incremental sales volume in the range of 75 to 90 percent. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRODUCT-LINE MANAGEMENT The popularity of product-line extensions as a strategy of choice by many firms raises the spectre of product cannibalism. The previous discussion suggests four implications of product cannibalism for product-line management. First, with companies coming under greater pressure to add new items to their lines, the need to systematically assess the incremental sales and profit contribution of product additions is becoming ever more critical. Specifically, it is important to quantify incremental product-line (versus single-product) profits before deciding whether to add a new item to an existing product line. Such incremental analysis requires an understanding of product cannibalism. Second, preemptive cannibalism is frequently necessary to confront competitor product development efforts. Nevertheless, productline filling and stretching efforts to meet competitive inroads need to be assessed by comparing cannibalized sales volume with projected lost volume. If cannibalized volume is substantially larger than projected lost volume, preemptive product cannibalism may not be justified. Third, understanding demand interdependencies is a necessary first step in assessing cannibalism potential. Traditional notions of crosselasticity of demand based solely on price are inadequate. Numerous other factors and conditions result in product substitutions. In this regard, effective product-line management must consider a new offering's "substitution-in-use" possibilities and hence its cannibalism potential. Finally, attention to the sources and magnitude of cannibalism produced by new offerings should be studied throughout the product 1 development process from concept through commercialization. To ignore product cannibalism is to invite unwise product proliferation and its frequent derivative—product cannibalism. NOTES 1. "New-Product Troubles Have Firms Cutting Back," Wall Street Journal (January 13, 1992), p. Bl; "Multiple Varieties of Established Brands Muddle Consumers, Make Retailers, Mad," Wall Street Journal (January 24 1992) pn Bl, B5. 2. Roger A. Kerin, Vijay Mahajan, and P. Rajan Varadarajan, Contemporary Perspectives on Strategic Market Planning (Boston: Allyn & Bacon Inc 1990), pp. 242-243. 3. Prescription for New Product Success (New York: Association of National Advertisers, 1984). 4. "Anheuser-Busch, Inc., Has Another Entry in 'Light Beer' Field," Wall Street Journal (February 19, 1978), p. 4. USER'S HANDBOOK 5. Judann Dagnoli, "How Stouffer's Right Course Veered Off Course," Advertising Age (May 6, 1991), p. 34. 6. Douglas J. Dalrymple and Leonard J. Parsons, Marketing ManagementStrategy and Cases, 4th ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1986), pp. 381-82. 7. "Miller Brewing to Test-Market New Light Beer," Wall Street Journal (April 20, 1988), p. 24. 8. For a recent description of the substitution-in-use approach, see S. Ratneshwar and Allan D. Shocker, "Substitution in Use and the Role of Usage Context in Product Category Structure," Journal of Marketing Research, (August 1991), pp. 281-295. 9. Dick Wittink and Philippe Cattin, "Commercial Use of Conjoint Analysis: An Update," Journal of Marketing (July 1989), pp. 91-96. 10. Albert L. Page and Harold F. Rosenbaum, "Redesigning Product Lines with Conjoint Analysis: How Sunbeam Does It," Journal of Product Innovation Management, 1987, pp. 120-137. 11. For further reading on conjoint analysis and possible applications, see Paul E. Green, Donald S. Tull, and Gerald Albaum, Research for Marketing Decisions, 5th ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1988). 12. Paul E. Green and V. Srinivasan, "Conjoint Analysis in Marketing Research: New Developments and Directions," Journal of Marketing (October 1990), pp. 3-19. 13. For an extended discussion on pretest market models, see Allan D. Shocker and William G. Hall, "Pretest Market Models: A Critical Evaluation," Journal of Product Innovation Management, 1986, pp. 86-107.