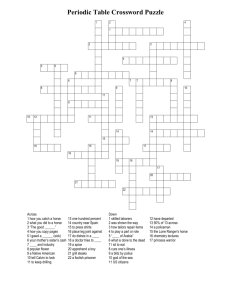

Horsemanship Quiz Challenge Study Guide

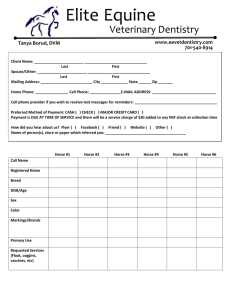

advertisement