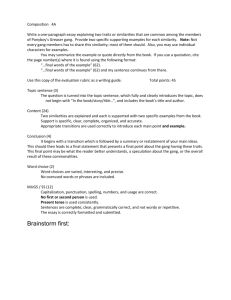

Are We a Family or a Business?

advertisement