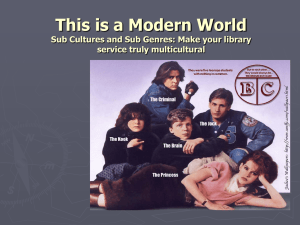

Youth Subcultures - Sociology Central

advertisement