Keating’s Lawyer

How Stephen C. Neal got the troubled

financier (almost) off the hook

By Stan Sinberg

PHOTOGRAPHY BY Gregory Cowley

Stephen C. Neal was facing a hostile

judge. He was arguing that his client, an

asbestos company facing bankruptcy,

shouldn’t have to pay out money to

“unimpaireds”—people with some evidence

of asbestos exposure but without as-yet

diagnosable medical conditions.

“What about these people who say they

get short of breath walking up stairs?”

the judge asked. “How do we value that?

They’re worried about getting sick soon.

How do we value that? How much do you

think a finger is worth, Mr. Neal?”

At which point the business litigator

stuck out his right hand, which happens to

be missing its pinky, and replied, “I can tell

you exactly what it’s worth in Cook County,

Illinois, your honor.”

It’s the kind of tale inveterate storyteller

Neal—who lost the finger in 1986 when he

was hit by a van and his hand got stuck

against the sideview mirror—delights in

relating. His quick wit has been known

to leave judges, opposing counsel and

cross-examined witnesses nonplussed.

(He reports ending up with a “great

settlement” in that 2003 case.)

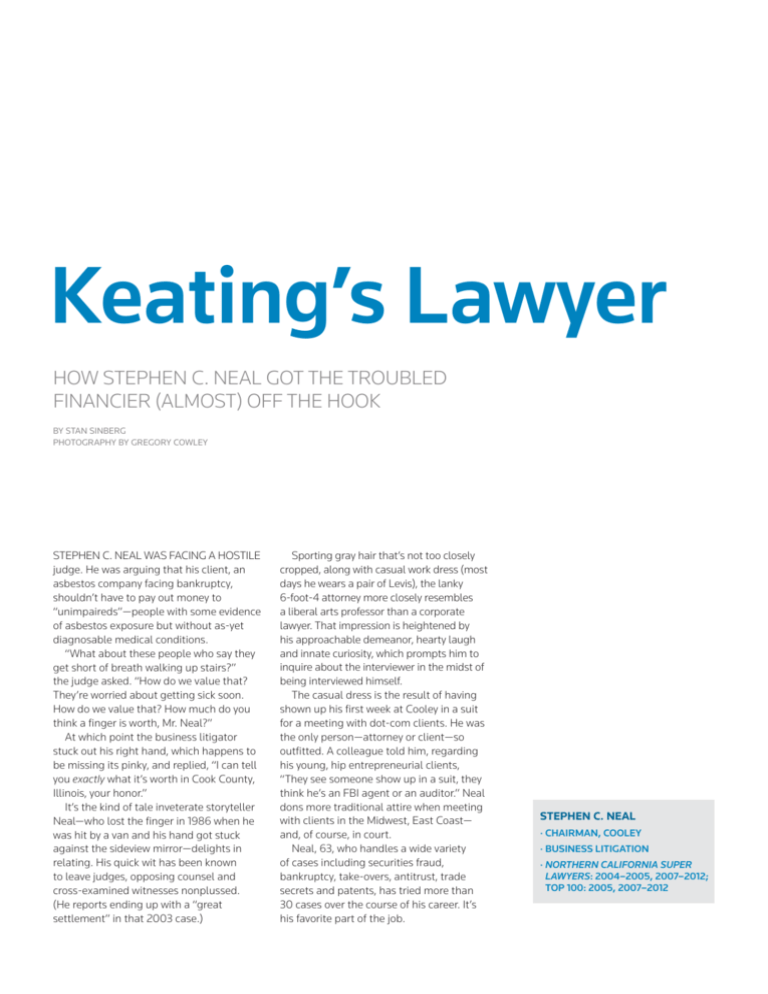

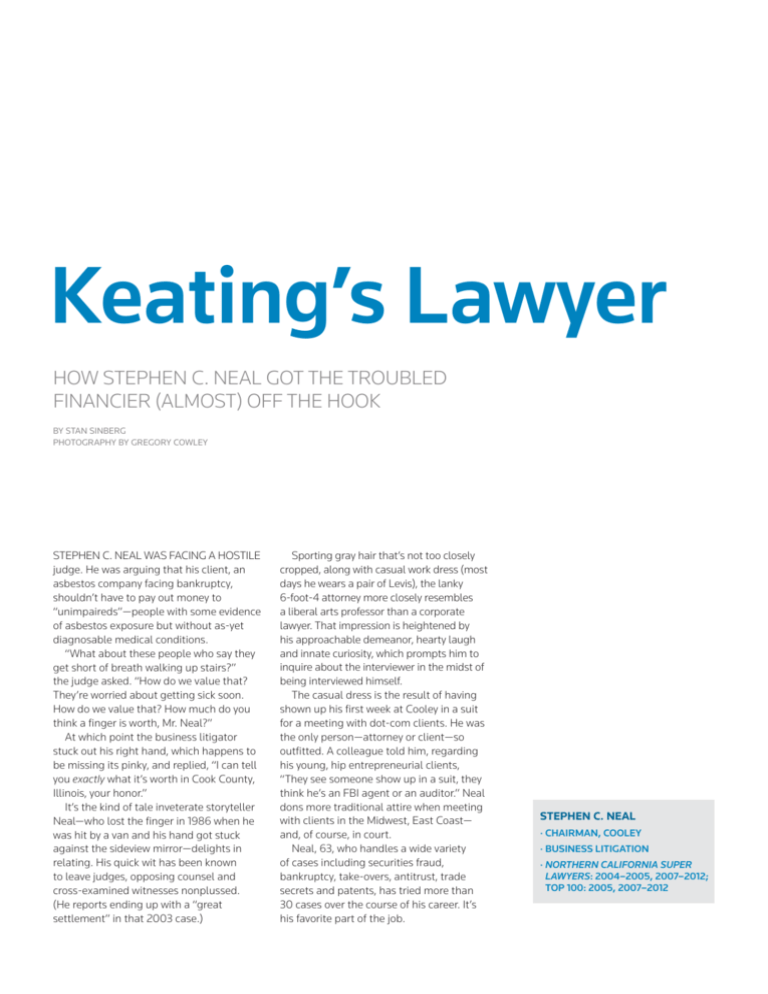

Sporting gray hair that’s not too closely

cropped, along with casual work dress (most

days he wears a pair of Levis), the lanky

6-foot-4 attorney more closely resembles

a liberal arts professor than a corporate

lawyer. That impression is heightened by

his approachable demeanor, hearty laugh

and innate curiosity, which prompts him to

inquire about the interviewer in the midst of

being interviewed himself.

The casual dress is the result of having

shown up his first week at Cooley in a suit

for a meeting with dot-com clients. He was

the only person—attorney or client—so

outfitted. A colleague told him, regarding

his young, hip entrepreneurial clients,

“They see someone show up in a suit, they

think he’s an FBI agent or an auditor.” Neal

dons more traditional attire when meeting

with clients in the Midwest, East Coast—

and, of course, in court.

Neal, 63, who handles a wide variety

of cases including securities fraud,

bankruptcy, take-overs, antitrust, trade

secrets and patents, has tried more than

30 cases over the course of his career. It’s

his favorite part of the job.

Stephen C. Neal

· Chairman, Cooley

· Business Litigation

· Northern California Super

Lawyers: 2004–2005, 2007–2012;

Top 100: 2005, 2007–2012

Back in 1989, he was retained by

Charles H. Keating Jr., whom he dubs “one

of the most vilified men of the last quartercentury.” Keating noticed that Neal was

getting his clients’ cases dismissed during

the Lincoln Savings civil litigation—one

of two lawyers to obtain that result out of

180 parties. Though Keating was fatalistic

about his trial prospects, he figured Neal

was an attorney who would build a good

case for an appeal.

Over the next several years, Keating

proved prescient: He lost his cases at trial,

but Neal got them all overturned on appeal,

including one that was ruled a violation of

due process based on instructions given

to the jury. After two years of negotiations,

Keating pleaded guilty to much more

limited bankruptcy charges, receiving no

fine and only time served.

Still, it is an earlier case that Neal touts

as his all-time favorite. Late one Friday

afternoon, he received a call from Inland

Steel management, whom he halfjokingly conjectures was “speed-dialing

for lawyers,” finding many gone for the

weekend or busy. Having worked at Inland

as a general laborer during college, Neal

thought, “I’ve made a lot of progress!”

After some 80 years, Inland Steel

was closing Sherwood Mine, located in

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The company

also ran the surrounding water-pumping

wells that kept the mines from flooding.

Inland Steel offered to sell the pumps to

the town for a dollar in lieu of shutting

them down. But the town, concerned

about operating costs and potential

liability, obtained a court order preventing

Inland from closing the pumps. Neal got

the case moved from state to federal

court, where a judge both granted Inland

the right to turn off the pumps, and Iron

River the right to sue Inland if flooding

resulted. The pumps were turned off

within 48 hours. Three months later,

floods engulfed Iron River.

At the trial, most of which was held in

the same Marquette, Mich., courthouse

where Anatomy of a Murder was filmed,

the plaintiffs' attorneys chided Inland

for bringing in “a Chicago lawyer.” The

plaintiffs then brought in David Todd

from UC Berkeley, considered the world’s

foremost water hydrologist. He appeared

on the witness stand with a globe and

pointed out 80 countries for whom he’d

consulted. On cross-examination Neal

asked Todd dryly, “Were you here when

they were giving me crap about coming

from Chicago?”

During the cross, Neal’s own local water

expert handed him a note. “Ask him to

describe for the jury the characteristics of

[Michigan’s] cedar swamps.” Todd drew a

blank, and Neal acted incredulous, serving

to undermine Todd’s local creds. Afterward,

a reporter came up to Neal. “There were

probably only two people in that courtroom

who didn’t have a clue about cedar

swamps,” the reporter said. “The witness

and the lawyer asking the question.”

Neal showed that the town had

periodically suffered floods over its history,

and argued that the recent flood just

coincided with the wells’ shutdown. The

jury ruled in favor of Inland Steel.

More recently, Neal got a call from

Kent Roberts, then-general counsel of

McAfee security-software company. It was

2006, and Roberts was in a tough spot.

The Department of Justice and the SEC

were issuing a flurry of investigations and

indictments of CEOs, CFOs and general

counsels, accusing McAfee and many other

companies of back-dating stock options.

Roberts was next in their sights, charged

by both agencies and summarily fired

from his job. Roberts hired Neal to fight

the charges, but the odds weren’t good:

The Justice Department’s record was 10

prosecutions; 10 guilty pleas or convictions.

Discovery started in late 2007, taking

place through the trial date, and about six

months afterwards. With the findings from

discovery, about a month before Roberts’

trial, the Justice Department dropped

four out of its seven criminal charges. On

the eve of the trial in 2008, Neal says he

finally got McAfee to turn over a number

of potentially exculpatory emails. When

U.S. District Judge Marilyn Patel saw

the correspondence—crucial to helping

exonerate Roberts—she declared, “Heads

will have to roll.” A jury subsequently

acquitted him, and shortly thereafter, the

SEC voluntarily dropped its case as well.

“Steve and his team got us the documents

that proved my innocence,” Roberts says. Of

13 people ever indicted on charges of backdating stock options, Roberts was the only

one acquitted by a jury.

In another recent case, Neal

represented Onyx Pharmaceuticals

against Bayer in a dispute that was

successfully settled eight days into

trial, granting Onyx co-rights to a drug

developed by Bayer under an ongoing

joint-development deal. Neal says

the drug has a number of potential

applications including treating colon,

kidney, liver and lung cancer.

Dr. N. Anthony Coles, Onyx’s president

and CEO, dubs Neal “a prince of a man.

From the start, Steve had great presence,

articulation and a dogged determinism

that we could win this case. He has a clarity

of thinking about the issues that others

can’t see, along with a great ability to

execute … a rare combination.”

Yet another major settlement came

in 2011, when Neal represented Nvidia

against chip-maker Intel, which claimed

it had the rights to some of Nvidia’s

graphics-processing information. Neal

relates telling Intel’s counsel, “I’m thrilled

you took action against us,” adding that

Nvidia hadn’t planned to sue Intel, but

since they “started it,” Nvidia would “finish

it.” Nvidia prevailed, and Intel had to fork

over $1.5 billion to continue licensing

Nvidia’s product.

Born in San Francisco, Neal grew

up on the peninsula and relocated at age

12 to Chicago’s South Side, an eclectic,

upscale and racially diverse neighborhood.

Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation

of Islam, lived two doors down; Joe Louis’

family lived across the street. The day

after Cassius Clay defeated Sonny Liston

(who lived around the corner) to become

heavyweight champion, Clay—who would

soon rename himself Muhammad Ali—

knocked on the Neals’ front door, offering

to buy the house. Neal and his three

brothers watched their parents’ reaction in

awe. “We were stunned that they wouldn’t

sell the house,” Neal says with a laugh.

Ali, who wanted to live near his spiritual

mentor, Elijah Muhammad, moved down

the block, and Neal periodically ran into Ali

at the local pizzeria. Elijah Muhammad’s

personal guards watched protectively over

everyone on the block, which was rounded

out by a house filled with basketballplaying Jesuit priests.

“For a 13-year-old moving from

the ‘WASP-y’ Stanford campus to an

integrated neighborhood with prizefighters—and [hearing the conversations]

the day Malcolm X was killed and Elijah

Muhammad was being blamed by some—

well, it was eye-popping,” Neal recalls.

The family’s moves were triggered by his

father’s career advancement. Phil Neal was

a law professor at Stanford, then migrated

to the University of Chicago Law School,

where he eventually became dean.

Neal says he wasn’t a particularly

good student in high school, so his father

devised a novel way to involve him in

academia: He made Neal read virtually

everything written on the cases of Sacco

and Vanzetti and Alger Hiss. The elder

Neal had worked for Hiss in the State

Department. These books instilled in

Stephen a deep sense of the importance

of due process.

While in college, Neal worked in a steel

mill and joined the union. “What I took away

from that experience is that I didn’t want to

be a steelworker,” he says with a laugh.

Upon graduating Stanford, he set his

sights on becoming a litigator. After Cooley

turned him down for a job, Neal returned to

Chicago, deeming it a great environment

for young lawyers, and specifically to

Kirkland & Ellis, where he’d spent the

summer before law school in a paralegaltype position.

After about two and a half years there,

a partner’s scheduling conflict led to Neal

trying his first big jury case. “A good number

of the jury were early middle-aged women

who probably thought I was their son,” he

says. “Juries are very forgiving of young

lawyers—they like to see them on their feet.

Most judges [also] understand that the very

lifeblood of our system is the continued

influx and development of new talent.”

One day while Neal was visiting

in California, co-chairing a fundraising

campaign at Stanford Law School with

Jim Gaither—then at Cooley—Neal took

him out for dinner. Gaither asked, “So

when are you coming home?” Neal replied,

“Damn, you’re good. I’m paying for my

own recruitment dinner.” A year later, Neal

jumped aboard.

After coming to Cooley in 1995,

Neal found that the high-profile cases

continued. He was named CEO and

chairman of the firm in 2001. Two

months later, the dot-com bubble burst,

necessitating the layoff of more than

100 attorneys and an equal amount of

staff. Neal was criticized in the media,

but he says there was just no work for

the attorneys. Some firms, he says, took

the same actions but disguised them

as “merit reviews” that both unfairly

stigmatized the young attorneys and

took longer, complicating their search for

other employment.

During Neal’s tenure as CEO, Cooley

opened offices in New York, Boston and

Washington, D.C. The firm also made a major

commitment to becoming a leader in pro

bono work, and now employs a partner full

time to administer pro bono activities. As for

Neal, mentoring the firm’s up-and-coming

attorneys is one of the best parts of the job.

“It’s enormously gratifying to watch those

younger lawyers keep emerging as superb,

skillful, front-line lawyers,” says Neal. “As a

profession, we get better every year.”

Reprinted from the August 2012 issue of Northern California Super Lawyers® magazine. © 2012 Super Lawyers®, a Thomson Reuters business. All rights reserved.