Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Infant Behavior and Development

Maternal anxiety, mother–infant interactions, and infants’ response to

challenge

Marsha Kaitz a,∗ , Hilla Rubin Maytal a , Noa Devor a , Liat Bergman a , David Mankuta b

a

b

Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel

Hadassah Hospital-Hebrew University Medical School, Jerusalem, Israel

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 9 September 2009

Received in revised form 4 December 2009

Accepted 28 December 2009

Keywords:

Anxiety

Maternal behavior

Mother–infant interactions

Emotion regulation

a b s t r a c t

Children of anxious mothers are at risk for social–emotional difficulties and disturbed, early

interactions with their mother may account for some of the risk. This study evaluated the

association between maternal anxiety, features of mother–infant interactions, and infants’

emotion regulation during stressful situations (still-face, play with a stranger). Thirty-four

anxiety-disordered mothers of 6-month-old infants and 59 typical dyads comprised the

sample. Dyads were filmed during free play, teaching, care giving, and face-to-face play;

and monadic (e.g., maternal sensitivity, infant affect) and dyadic measures (e.g., synchrony)

were derived by global or time-event coding of the films. Results indicate that, compared to

controls, more anxious mothers showed exaggerated behavior with their infant during free

play and teaching, and infants of anxious mothers were less likely to show negative affect

during the still-face and stranger challenges. We conclude that anxious maternal behavior

reflects the hyperarousal that is characteristic of most anxiety disorders; and infants of

anxious mothers and controls show differences in the manner in which they cope with

social challenges.

© 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Anxiety disorders affect millions of adults world wide, causing them significant distress and difficulties in daily functioning

(Barlow, 2002). Anxiety disorders can last for years and can get worse if they are not treated. Anxiety disorders commonly

occur along with other mental health disorders such as depression, which may mask anxiety symptoms or make them worse.

Of especial concern, anxiety seems to run in families so that children of parents with anxiety disorders are at higher risk for

developing anxiety disorders and other developmental disorders than are children of healthy parents (Schreier, Wittchen,

Höfler, & Lieb, 2008). Research on the processes by which anxiety can be transmitted to offspring are needed in order to

identify potential routes of transmission and to discern early signs of perturbed development in children of anxious parents

(Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

Considering this, we carried out a study in order to identify distinctive features of interactions between anxious mothers and their infants and to look for early effects that maternal anxiety might have on the young. The research follows a

number of studies on depressed mothers that have shown that their interactions with their infants are marked by mothers’

more prevalent negative affect, less sensitive responsiveness, and less frequent shared behavioral states with their infants,

particularly in samples with multiple adversities (e.g., Field, Healy, Goldstein, & Guthertz, 1990; reviews in: Goodman,

∗ Corresponding author at: Department of Psychology, Hebrew University, Jerusalem 91905, Israel. Tel.: +972 2 5883372; fax: +972 2 5881159.

E-mail address: msmarsha@mscc.huji.ac.il (M. Kaitz).

0163-6383/$ – see front matter © 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.12.003

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

137

2007; Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000; Reck et al., 2004). Research also provides strong evidence that these kind

of interactions can forecast developmental problems beginning at a very young age (reviews in Field, Hernandez-Reif, &

Diego, 2006; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998a). More generally, these studies are part of a larger literature that demonstrates

that mother–infant interactions are important social experiences for infants and, in atypical form, can lead to problems in

important developmental domains (Feldman, Greenbaum, & Yirmiya, 1999; Isabella & Belsky, 1991; Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman,

& Parsons, 1999; reviews in Schore, 2001; Swain, Lorberbaum, Kose, & Strathearn, 2007).

1.1. Maternal anxiety and mother–infant interactions

There are only a few studies in which highly anxious mothers have been observed with their infants, and findings regarding

distinctive features have been variable and in some studies, difficult to interpret. For example, Weinberg and Tronick (1998b),

using a mixed sample of women with panic disorder, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder, reported pervasive

difficulties in aspects of mother–infant interplay, though as noted by the authors, the effects of anxiety cannot be discerned

because of the makeup of the sample. In a second study, Warren et al. (2003) compared panic-disordered (PD) mothers of

4 or 14-month-old infants to control dyads and reported significant group differences in maternal sensitivity and in some

parenting techniques. The infants of the probands had more sleep problems and higher levels of cortisol than did infants

of controls, although the groups did not differ on other measures (high reactivity, behavioral inhibition, or ambivalent

attachment). As in Weinberg and Tronick (1998b), it is difficult to ascribe these differences to anxiety per se because the PD

women had other disorders, including depression.

Using a more diagnostically homogenous sample, Murray, Cooper, Creswell, Schofield, & Sack (2007) found less pervasive,

but still significant differences between the interactions of anxious dyads and healthy ones. In that study, mothers with social

phobia (SOP) were described as no less sensitive to their 10-week-old infants than were control mothers; but they engaged

their infant less and looked more anxious than controls. Further, in the context of a social challenge (stranger–mother–child

interaction), the mothers with SOP looked more fearful and were less encouraging of their infants’ engagement. Interestingly,

mothers with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were also less engaged with their infant during dyadic play, but showed

no differences from controls during the stranger challenge. For their part, infants of mothers with SOP were less positively

engaged with the stranger than were infants of controls; this was not the case for infants of mothers with GAD. Notably,

the exclusion of women with depression from the sample did not change the pattern of results, thus demonstrating that

depression was not a confounding factor. Finally, in the most recent study; Weinberg, Beeghly, Olson, & Tronick (2008)

observed anxious (PD, without depression) and control mothers with their 3-month-old infants and found no distinctive

markers of anxiety among a large array of monadic and dyadic measures, though this may be due to the small size of the

sample (n = 13). Besides these studies, there are others that have reported a relation between mothers’ anxiety symptoms

(not diagnoses) and deficits in maternal and/or infant behavior (e.g., Blissett, Meyer, & Haycraft, 2007; Feldman, Greenbaum,

Mayes, & Erhlich, 1997; Field et al., 2005; Nicol-Harper, Harvery, & Stein, 2007; Nover, Shore, Timberlake, & Greenspan, 1984;

Stifter, Coulehan, & Fish, 1993; also see Wijnroks, 1999), however, the women in these samples usually were not anxious

(according to their symptom scores), so the results may not be generalizable to clinical samples.

In summary, the findings so far do not provide a coherent picture of anxious mother–infant interactions. More data are

needed to discern markers of anxious maternal behavior and developmental difficulties among children of highly anxious

mothers.

1.2. The present study

In the present study, we filmed clinically anxious mothers and their 6-month-old infants and compared their behavior to

that of healthy dyads. We also looked for group differences in the infants’ responses to challenge. Probands were diagnosed

for current anxiety so that we could relate their mental health to their concurrent behavior. In Warren et al. (2003), women

were diagnosed for lifetime (not necessarily current) disorders; in Weinberg et al. (2008) and in Murray et al. (2007), women

were diagnosed during pregnancy, though in the latter study, symptomology was confirmed by short symptom inventories

at the time of testing.

To derive a comprehensive picture, we filmed anxious and control dyads in varied episodes that simulated interactions

that mothers and infants have together on a routine basis (floor play, teaching, care giving). In addition, mothers and infants

were filmed during the still-face paradigm (SFP, Tronick, Als, Adamson, Wise, & Brazelton, 1978), in which mothers play

face-to-face with their infant, then adopt a “still-face”, and then resume face-to-face play. Infants also were filmed during an

interaction with a playful stranger. Using data derived from the still-phase phase of the SFP and from the stranger episode,

we looked for signs of atypical (infant) emotion regulation, succinctly defined as the “. . . extrinsic and intrinsic processes

responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions” (Thompson, 1994, pp. 27–28). In many studies,

infants’ emotion regulation has been assessed by examining infants’ responses to mild challenges (e.g., Haley & Stansbury,

2003; Moore & Calkins, 2004; Moore, Cohn, & Campbell, 2001), and this was the tact taken in the present study. Importantly,

early difficulties in emotion regulation can predict later developmental difficulties, including fearfulness and anxiety, in

some children (Degnan & Fox, 2007; Park, Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1997).

We addressed three research questions:

138

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

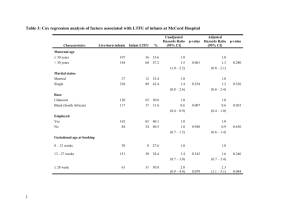

Table 1

Characteristics of the control (N = 59) and anxious (N = 34) groups.

Controls

M

Anxious

SD

Girl infants

Native Israeli

Seculara

Employedb

%

54.2

83.1

28.8

56.1

n

32

49

17

32

%

52.9

76.5

41.2

67.6

n

18

26

14

23

Education

High-school

Prof. train.

BAc

MAc

PhDc

8.5

16.9

62.7

10.2

1.7

5

10

30

6

3

11.8

11.8

35.3

38.2

2.9

4

4

12

13

1

Treatment

Therapy now

Past therapy

Meds nowd

1.7

13.6

.0

1

8

0

11.8

29.4

5.9

4

10

1

a

c

d

26.06

15.66

SD

25.11

15.19

b

4.07

2.39

M

Age

Education (year)

3.99

1.71

Secular vs. conservative, religious, or orthodox (all women were Jewish).

Employed outside of the home.

Completed or in progress.

Psychotropic medication.

(1) Do clinically anxious mothers and their infants show atypical features in their behavior during (non challenging) mutual

interactions? Without a clear direction from previous studies, we refrained from hypothesizing which behaviors distinguish anxious dyads from controls during non-stressful play.

(2) Do anxious dyads have a particularly hard time in realigning their social interplay after the still-face challenge? Tentatively, we predicted that they do (despite the null findings of Weinberg et al., 2008), assuming that the stress of the

still-face condition would exacerbate the anxiety symptoms of anxious mothers and, as a result, it would take anxious

dyads longer to recover from the still-face challenge than it would, control dyads (Ham & Tronick, 2006).

(3) Do infants of anxious mothers show atypical emotional responses to challenges? We considered this likely, but did not

predict whether infants of anxious mothers would show more distress or less distress than infants of controls. This is

because, on one hand, infants of anxious mothers may be vulnerable to distress if indeed they have been routinely stressed

by anxious maternal behavior (Kopp, 1989) or other factors associated with having a highly anxious mother (Rutter,

2005). On the other hand, a history of unresponsive or overzealous care by anxious mothers could interfere with their

infants’ natural tendency to call out to their caregiver (i.e., signal distress) for comfort (Bowlby, 1980, 1988). Significantly,

either outcome would constitute evidence of atypical development among infants of highly anxious mothers.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The sample was comprised of first-time mothers and their 6-month-old infants. The anxious group was comprised of

34 women diagnosed with a current anxiety disorder (13 with panic, 8 with social phobia, and 13 with PTSD) without

(lifetime) depression. The control group was comprised of 59 controls who did not meet (DSM-IV, American Psychological

Association, 1994) criteria for (lifetime) clinical or sub clinical anxiety or depression (see Table 1 for demographics and

background information). As stipulated by inclusion criteria, the women in both groups were 20–40 years old, married,

primiparae, conceived naturally, had completed high-school, and had no serious physical conditions. Inclusion criteria also

required that the infants were born at full-term without complications, and had no serious health problems.

2.2. Recruitment and attrition

This study received ethic committee approval from the urban hospitals in which women were recruited. Women also were

recruited government-subsidized well-baby clinics up to 2 weeks after childbirth. On recruitment days, all first-time mothers

with healthy infants were asked for (written) permission to contact them when their infant was 1-month-old in order to tell

them more about a study on mothers’ feelings and infant development. Most of the women (920/980) agreed to be contacted

at one month postpartum; the 60 women who refused cited reasons including their unwillingness to participate in research

or their plans to move away. Of those who agreed to be contacted, 78 women could not be reached after trying on four

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

139

consecutive days at different hours of the day. Of the 842 women who were contacted at one month, 780 were interviewed

by phone at 5-months postpartum in order to screen them for anxiety and depression, evaluate anxiety symptomology, and

procure their agreement to come to the lab when their infant was 6-months old. The other women (n = 62) could not be

reached after four attempts at contact or were no longer interested in participating in the study.

The women who were interviewed at 5-months postpartum and answered yes to an anxiety screening question but no to

the depression screening question, and agreed to continue in the study were targeted for the anxiety group (82); those who

screened negative for depression and anxiety were targeted for the control group (178). Of these 260 women, 30 women

(18 targeted for control group and 12 targeted for the anxious group after screening, X2 , p > .05) could not be scheduled for

the lab session because of the mothers’ working hours (5), infants were more than 6.5 months old when contact was made

with their mothers (2), mothers could not be reached by phone (12), or mothers refused to come to the lab (11). The other

230 came to the lab where they were diagnosed and filmed; and of these, 59 met final criteria (see below) for the control

group and 34 met criteria for the anxious group. In sum, the total refusal and attrition rate of this study was 23.5% (230/980).

2.3. Diagnosis assessment

Current and lifetime diagnoses were based on the background interview and the anxiety and depression modules of

the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), supplemented with Beck symptom inventories for

assessment of the severity of depression and anxiety symptoms (Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI; Beck Depression Inventory,

BDI). Women who did not meet diagnostic criteria for threshold or subthreshold, current or lifetime disorders and scored

less than 9 on the BAI and BDI were eligible for the control group. Inclusion in the anxious group required a diagnosis of

one or more current (threshold) anxiety disorders; but excluding women diagnosed with “only” a specific phobia (n = 7) and

those diagnosed with an anxiety disorder plus depression at any time in their lives (n = 8). Women with “just” a specific

phobia were excluded (from the control and anxious groups) because phobias are highly specific to certain stimuli (e.g.,

animals, blood); and we presumed that, by themselves, they would not interfere with mothers’ behavior toward their infant.

Women with depression were excluded from the sample so it would not obscure effects of anxiety on mothers or infants.

Diagnostic interviews were conducted by psychologists or advanced psychology students after intensive training that

involved a review of DSM disorders, memorizing the SCID interview, review of training tapes, and structured role playing

over the course of several months. All interviewers reached agreement on at least 9/10 (anxiety disorder) training tapes

prior to interviewing subjects for this study. Diagnoses made during the study were reviewed in weekly staff meetings with

a psychologist in order to ascertain the reliability of diagnoses and maintain standards. Reliability between interviewers

was estimated on the basis of 10 taped interviews, and all of the classifications (anxious, control, depression) matched the

original ones ( = 1.00).

2.4. Diagnostic and assessment tools

2.4.1. Anxiety Screening Questionnaire (ASQ-15, Wittchen & Boyer, 1998)

The ASQ-15 is a diagnostic-specific, self-report screening measure for anxiety syndromes and depression. Each item

represents the primary criteria for a DSM-IV anxiety or depression disorder and is answered as yes or no. Test–retest

reliability and validity, when compared to DSM-IV diagnoses, has been shown to be good when the tool is administered by

telephone, as in this study.1

2.4.2. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID IV, research version; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams,

1996)

This modular, semi-structured interview for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders has become the general standard and

provides lifetime and current diagnoses.

2.4.3. Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories (BDI, Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961; BAI, Beck, Epstein,

Brown, & Steer, 1988)

Both the BDI and BAI consist of 21 disorder-related symptoms (rated in severity, 0–3) and are frequently used self-report

measures. The inventories have good psychometric properties and are among the best self-rating tools for discriminating

anxiety from depression (Clark & Watson, 1991).

2.5. Observations

Observations were made in a play room in our laboratory, designed to be welcoming and comfortable for mothers and

infants. One standing camera was used to film the free play, teaching, and care giving episodes; and two wall-mounted

1

In addition to these assessment tools, mothers were administered the Infant Characteristics Questionnaire (fussy-difficult dimension only) (Bates,

Freeland, & Lounsbury, 1979). Results showed no group differences in infant temperament (M (SD): infants of controls 20.92 (4.90), infants of anxious

mothers 22.67 (6.59), with higher scores reflecting more difficult temperament). Results were not altered by the addition of temperament as a covariate.

140

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

cameras (one focused on the mother and the other on the baby) were used to film the face-to-face interactions. The signals

from these two cameras were transmitted through a digital timer and a split-screen generator into a video recorder to

produce a single image with a simultaneous front view of mother’s face, hands, and torso and the infant, in full view. This

configuration allowed for separate coding of mothers’ and infants’ behavior during the face-to-face interactions.

The order of the episodes was as follows: free play, teaching, still-face paradigm (SFP), face-to-face play with a stranger,

and care giving. Episodes began when the infants were alert and showed no signs of impending distress. If an infant became

very distressed (cried strongly for 10-s) during the still-face phase of the SFP, the reunion episode was initiated immediately

unless the infant was too distressed to continue. In these cases, the SFP was suspended and the infant was calmed prior to

beginning the stranger episode. If the infant could not be calmed, the SFP was terminated and the dyad did not partake in

the reunion phase. The episodes are described below.

2.5.1. Free play, teaching, care giving (floor episodes)

During these episodes, mother and infant were seated on the floor of the play room on a padded rug with a colorful sheet

over it. For the free play episode (5-min), several standard toys were placed on the sheet, and mothers were asked to play

with their infant. For the teaching episode (5-min), mothers were given a set of stackable, plastic boxes and asked to “teach

their infant the game”. For this episode, we purposely chose a game that was more appropriate for older infants because

we thought that teaching it to a young infant could elicit frustration and intrusive behavior on the part of parents who are

prone to such behavior. For the care giving episode (unlimited time), we asked mothers to dress the child in pajamas that

had “feet”, long sleeves, and snaps up both legs. Care giving was chosen as a task because it is a routine activity for mothers

and infants and may require some degree of negotiation if mothers’ and infants’ agendas are not the same.

2.5.2. Face-to-face still-face paradigm (with mother, SFP; Tronick et al., 1978)

During this episode, which is comprised of three phases, infants were seated in a baby-seat on a table facing their mother.

In the first phase, mothers and infants played freely without toys or use of a pacifier (face-to-face play, 2-min); in the second

phase, mothers gazed at their infant but did not respond to him/her (still-face, 2-min); in the third phase, mothers resumed

play with their infant (reunion, 2-min).

2.5.3. Stranger–infant face-to-face play

In this episode, infants and a stranger (one of six female research assistants) played face-to-face for 2-min. This episode

provided information on infants’ regulation of affect when faced with an unfamiliar person (without mother in sight).

2.6. Coding

Two types of coding were employed: global ratings on Likert scales reflecting important features of social interactions,

and time-event (continuous) coding that affords details about the timing of targeted responses (i.e., when they occurred

and for how long). In this study, free play, teaching, and care giving episodes (floor episodes) were coded by global ratings;

face-to-face interactions and infants’ affective behavior during the still-face phase and stranger episode were coded by

time-event coding.

2.6.1. Free play and teaching

Films were coded on 14 scales, adapted from the Rating Scale of Interactional Style (RSIS; Clark & Seifer, 1983) The RSIS

is a validated scoring system based on a 5-point Likert scale, with low scores reflecting no or infrequent shows of targeted

behavior and high scores reflecting frequent and clear shows. Behaviors coded for mother were: Overriding (parent disrupts

child’s ongoing behavior), Forcing (mother manipulates child physically), Imitation, Acknowledging (mother’s responsiveness to infant’s signals), Gaze (mothers’ focus on child or object of joint attention), Positive affect, Range of affect (range of

emotional expression accords with infant’s emotions, state, and activity), Vocalization (“motherese”), Sensitivity (supportive

presence), and Reciprocity (“give-and-take”). Infant scales included: Positive affect, Fussy, Initiation of play bids, and Positive

vocalization. These scales are similar to those used in previous mother–infant observation studies (Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Zoll,

& Stahl, 1987), including ones on maternal anxiety (Feldman et al., 1997).

For more detail and because hyperarousal is a common symptom of anxiety disorders (Grillon, 2008), coders entered

an “E” next to ratings of mother’s vocalization, acknowledgements, (positive) affect, and gaze if the observed behavior

was “exaggerated” (e.g., overly intense, too frequent; as in Bohlin & Hagekull, 1987). Together, the numerical rating (1–5)

reflected the degree of mothers’ sensitivity, and the E noted whether their behavior was exaggerated or not. For example, if

a mother spoke to her infant in a generally adult tone, but with some intonation and did so near-incessantly or very loudly,

Vocalization would be rated as a 3 (i.e., moderately sensitive), with an E. If a mother spoke with moderate sensitivity to her

infant, but the frequency and loudness of her vocalizations were considered “normal”, Vocalization would be coded as a

3, without an E. A previous study reported a negative relation between the number of Es and scores of infant’s “adequate”

interactive behavior (Bohlin & Hagekull, 1987).

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

141

2.6.2. Care giving

The coding protocol for the care giving episode was taken from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care Mother–Infant

Interactions (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1997; Owen, unpublished). This protocol includes the following

scales: for mother – Negative Regard (shown in voice, touch, affect to infant), Sensitivity (appropriate, responsiveness,

warmth, and reciprocity), Positive Regard; for infant – Positive Affect, Negative Mood (negative expressions or vocalizations),

Sociability (bids for engagement). All of these behaviors were rated 1–4, generally reflecting “none” to “a great deal”. This

protocol was selected for coding the care giving episode, instead of the more detailed one used for free play and teaching,

because the care giving episode was often shorter than the other floor episodes; and infants’ responses during care giving

were somewhat limited due to the nature of the task. Previous studies have found a relation between maternal sensitivity

assessed by the NICHD scales at 6-months postpartum and infants’ attachment security at 15-months of age (McElwain &

Booth-LaForce, 2006).

2.6.3. Face-to-face interactions

Mothers’ and infants’ behavior was coded continuously according to the Infant and Caregiver Engagement Manual

(Weinberg & Tronick, 1999), which is based on the Monadic Phases Scoring System (Als, Tronick, & Brazelton, 1979). Monadic

phases are independent response categories created for the coding of second-by-second changes of affective engagement

during face-to-face interactions and represent a continuum from negative to positive engagement. Monadic phases were

defined as: (1) protest/negative; (2) withdrawn; (3) object/environment engagement; (4) social monitor; (5) play. Coding of

mothers’ and infants’ behavior was carried out separately, off-line using a computerized coding system (Noldus Observer,

version 5.031, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands). Each coder used the exact same time for starting

the coding of each episode. During coding, each film was run at normal speed until a phase change was noted, then reversed

and played back at slow speed to enter the exact time of change.

2.6.4. Infant emotion regulation

Infants’ affective responses to the still-face and stranger were coded continuously for positive affect (smiles) and negative

affect/distress (e.g., looks sad, whimpers, cry).

2.7. Controls and reliability

Coders were trained extensively to at least K = .70 and 80% reliability on all measures; and all of the coders were blind as

to the mothers’ group-placement. To eliminate a potential source of bias in coding, coders were charged with coding one

episode only and, for the SFP, assistants coded either mother or infant, in one phase of the paradigm.

To assess interobserver reliability, 20% of each floor episode and each phase of the SFP and stranger episodes were selected

randomly and coded independently by two coders. For the floor episodes, mean intra-class correlations were: .82 (range

.76–.88) for maternal behavior and M = .92 (range .80–.96) for infant behavior.

For tests of inter observer reliability of time-series codings, percent agreement (defined as the proportion of time

that the two coders made identical ratings in the same 1-s interval) was evaluated by using the formula: agreements/agreements + disagreements. The number of times both coders agreed that a score did not occur was not considered

in this calculation to avoid inflating agreement. So calculated, mean agreement for mothers’ affect during face-to-face play

was .83 (range .76–.87), for infants’ affect during face-to-face play, .82 (range .72–.88), and for infants’ affect during challenge

(still-face and interaction with a stranger), .85 (range .78–.89). Reliability kappas also were conducted in 1-s time windows

and were M = .84 for mothers’ time-series (range .75–.89), M = .76 for infants’ time-series (range .74–.84) during face-to-face

play, and .79 (.77–.86) for infants’ affect during the challenging episodes.

2.8. Data reduction and final measures

2.8.1. Free play and teaching

Following previous studies on maternal anxiety and depression (Feldman et al., 1997), ratings on the RSIS scales were

averaged into three composites (per episode): Mother Sensitivity, Mother Intrusiveness, and Infant Involvement (see Table 2

for components of composite measures and estimates of coherence, Cronbach alpha). As defined here, Maternal Sensitivity represents the same sensitive–responsive construct, with minor variations, described in many longitudinal studies of

mother–infant interactions (e.g., Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Crockenberg & McClusky, 1986; Kogan & Carter,

1996). Maternal Intrusiveness was included as a measure because it or similar constructs (overprotection, control) have

been related to anxiety in mothers of infants (Feldman et al., 1997) and theoretically (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998) and empirically to the development of anxiety in children in some studies (review in Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, & Chu, 2003;

meta-analysis in McLeod, Wood, & Weisz, 2007). Infant Involvement assessed the infant’s active participation in play and

the level of expressed positive affect. The final measures of exaggerated behavior reflected whether or not the mother had

shown exaggerated behavior in the free play or teaching episode.

142

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

Table 2

Composite measures of mother–infant interaction and scale coherence (Apha Cronbach, ˛).

Composite measure

Individual scales

Free play and teaching (global coding, 1–5)

Maternal sensitivity

Sensitivity, acknowledgement of infants’ signals + vocalization in the infant register + reciprocity + range of

affect + gaze + positive affect + imitation (free play ˛ = .85; teaching ˛ = .88)

Maternal intrusiveness

Over-riding (nonphysical coercion) + forcing (physical intrusiveness) (free play ˛ = .63; teaching ˛ = .78)

Infant involvement

Positive affect + positive vocalization + fussy (rev) + initiation of play bids (free play ˛ = .72; teaching ˛ = .74)

Care (global coding, 1–4, measure defined as mean rating)

Maternal sensitivity

Sensitivity + positive regard + negative regard (rev) (˛ = .84)

Infant affect

Positive affect + sociability + negative mood (rev) (˛ = .76)

Face-to-face (play and reunion, time-event coding)

Protest or sad expressions (rating 1 or 2)

Negative affecta

Show of social monitor or social play (rating 4 or 5)

Positive affectb

Infant regulation: stranger and still-face challenge (time-event coding)

Infant negative affect

Infants’ negative expression

Infant positive affect

Infants’ smile

a

b

Infants only.

Mother and infants, separately.

2.8.2. Care giving

Ratings of behavior during the care giving episode were reduced to two composite measures (Maternal Sensitivity and

Infant Affect), which reflected mothers’ sensitivity while dressing their infants and infants’ emotional state during the

episode.

2.8.3. Face-to-face play and reunion

Monadic and dyadic measures were obtained from the face-to-face play and reunion episodes. The monadic measures

were based on the proportions of the interaction (total seconds/total duration of episode) that mother and infant (separately)

were in a positive (social monitor or social play) or negative (anger/protest or withdrawn) state.

Proportions of mothers’ positive affect and infants’ positive affect during face-to-face play were arc-sine transformed

prior to analysis to correct for skewness of their distributions. Mothers’ proportions of negative affect were not analyzed

because so few mothers (<20%) showed negative affect during face-to-face play. Infants’ negative affect during face-to-face

play was highly skewed and recoded as dichotomous, as in Forbes, Cohn, Allen, and Lewinsohn (2004) among others. In sum,

final monadic measures included: (transformed) percent time in positive state for mother and infant and dichotomized

negative state for infant.

To derive the dyadic measures, we followed previous studies (Cohn & Tronick, 1988; Weinberg, Tronick, Cohn, & Olson,

1999) and averaged ratings within each 1-s period, resulting in one time-series for mothers’ behavior and one time-series

for infants’ behavior for each face-to-face interaction. From these data, four measures of dyadic coordination were derived.

(1) Matching: This measure is defined as the extent to which mothers and infants shared joint affective states at the same

moment in time (i.e., within the same 1-s interval). A measure of matched affect has been used by Weinberg et al. (1999)

and others (e.g., Field et al., 1990; Tronick & Cohn, 1989). As in these studies, matching was calculated as the proportion

of total interaction time that mothers and infants were in the monadic phase of social monitor or social engagement in

the same 1-s interval (social match). This measure was arc-sine transformed prior to analysis to correct for skewness

of its distribution. Proportion of time in negative matches was not subjected to analysis because there were few such

matches during mother–infant face-to-face interactions.

(2) Degree of synchrony: Whereas matching focuses on temporal contiguity and content of behavior (i.e., valence of expressions), synchrony focuses on the extent to which mothers and infants change their affective states together over time,

regardless of the content of their behavior. Thus some dyads may seldom be in matching states but may have high

synchrony scores because infant and mother tend to change in the same affective direction over the course of the

interaction.

As elsewhere, synchrony was computed separately for each dyad using time-series analysis of the two time lines

(one for mother and one for infant) describing the second-by-second changes in monadic states across each face-to-face

interaction. Derivation of synchrony involved the following steps: First, we “removed” the auto-correlated component

of the time-series that reflects the natural tendency to cycle between states of engagement and disengagement, The

auto-correlated component was estimated using separate Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) models

for each series, and the best model was estimated, according to autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation plots (i.e.,

visual representations of the time-series and its autocorrelation matrix at different lags). Residuals of the “best model”

were then checked for lack of autocorrelation. Second, cross correlation functions (CCF) for each dyad were computed

with the two series of residuals, and the largest cross correlation coefficient on the CFF plot was taken as degree of

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

143

synchrony, which ranges from zero, implying no association between the two time-series to one, describing a perfect

match between the two time-series.

(3) Lead–lag relations: Lead–lag relations reflect the direction of dominance in the interaction and identify that partner

who is leading the changes in affective states across the interaction. Lead–lags are derived only when the interaction

is synchronous and when significant relations are found between the partners’ behavior, meaning that the CFF was

significant and at least one significant peak appeared on the CFF plot. A dyad received a score of one, if there was a

positive peak (parent follows infant), 0 if there was a negative peak (infant follows parent), and 2 if there was a negative

and positive peak (mutual synchrony).

(4) Time-lag-to-synchrony: The time-lag-to-synchrony variable indicates the time in seconds between change in one partner’s behavior and corresponding change in the other’s or as described elsewhere, “the time required for the dyadic

system to settle into a coregulated exchange” (Feldman, 2003, p. 11). Similar to the lead–lag relation variable, the

time-lag-to-synchrony variable assumed a positive value only when at least one significant peak appeared on the CCF.

The time-lag to the first significant peak, whether positive or negative, was used to index time-lag-to-synchrony. The

time-lag-to-synchrony variables were within the range of 1 (implying one second to the partner’s responsiveness) and

7.

2.8.4. Infants’ emotion regulation

The proportion of time that infants’ showed positive affect or distress to stranger and to mothers’ still-face was sharply

skewed and dichotomized prior to analyses. Accordingly, the two measures reflected whether or not the infants expressed

distress or positive affect during the each of the challenging episodes.

2.9. Data analysis

Preliminary analyses tested the normality of measures; and if kurtosis or skewness was unacceptable (see Tabachnick &

Fidell, 1996), variables were transformed as described in Sections 2.8.3–2.8.4. Additionally, we tested for group differences

on background measures. To examine the reliability and validity of final measures, correlations and regression models

evaluated the stability of measures across episodes and tested for relations between mothers’ and infants’ behavior within

episodes.

To address question 1, multivariate and univariate analyses (general linear models, GLMs) were used to compare anxious

and control groups on continuous behavioral measures (maternal sensitivity, maternal intrusiveness, infant involvement)

derived from the floor episodes and the 1st face-to-face interaction; chi square was used to test for group differences on the

dichotomous variable (infants’ negative affect). Log-linear analysis tested for group differences in lead–lag relations.

To address question 2, (transformed) continuous measures (social play and social monitor, positive match, degrees of

synchrony, time-lag-to-synchrony) derived from the 1st face-to-face interaction and the reunion episode were compared

by univariate repeated measure GLMs, with episode as the repeated measure. A multivariate analysis across measures was

not employed because final measures were derived from the same raw data and therefore were not strictly independent.

To test for group differences in categorical measures (infants’ negative affect, lead–lag relations) during the 1st and reunion

face-to-face interaction, data were subjected to separate conditional logistic regression analyses (for repeated measures;

Agresti, 1996).

To address question 3, we compared the proportion of infants in each group who showed positive affect and negative

affect in each of the two challenging by chi square analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

3.1.1. Missing data

Data on free play are missing on one dyad due to technical (camera) problems; no data are missing from teaching or the

1st face-to-face interaction. No data are missing from the stranger episode or the still-face phase of the SFP, although for two

infants, the latter was terminated early because they became very distressed. The data from four controls and two anxious

dyads are missing from the 2nd face-to-face interaction because the infants were too distressed after the still-face challenge

to continue onto the reunion. Two dyads did not partake in the care giving episode because the infants were too tired.

3.1.2. Demographics and background

There were no group differences in mothers’ age, religiosity (secular vs. religious), working status (employed, not

employed), or education (Table 1). The anxious group scored significantly higher than the control group on both the

BAI (M = 5.80, SD = 4.11 vs. M = 1.49, SD = 1.84, t (91) = 6.86, p < .0001) and BDI (M = 5.68, SD = 4.45 vs. M = 2.46, SD = 2.53, t

(91) = 4.30, p < .0001). As noted in Table 1, very few women in the anxious group and control group were in therapy or taking

psychotropic medication at the time of the observation.

144

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

Table 3

Mean scores of behavioral measures obtained from free play, teaching, and care giving episodes, by group.

Controls

*

Anxious

M

SD

M

SD

Free play

M. Sensitivity

M. Intrusive

I. Involve

3.56

1.76

4.34

.63

.77

.48

3.73

1.72

4.27

.66

.73

.63

Teaching

M. Sensitivity

M. Intrusive

I. Involve

3.76

1.95

3.97

.68

.79

.76

3.60

1.80

3.78

.68

.76

.85

Care

M. Sensitivity

I. Affect

3.15

2.78

.59

.82

3.23

2.89

.43

.79

p < .05.

3.1.3. Measures of maternal and infant behavior: reliability and validity

(1) Correlations across episodes: Significant correlations were found between measures of maternal sensitivity (free

play–teaching, r = .43, p = .0001; teaching–care, r = .21, p = .04, but not between care giving-free play), maternal intrusiveness (free play-teaching r = .31, p < .0001), and mothers’ affect during face-to-face interactions (r = .32, p = .0001). Measures

of infants’ behavior were also correlated across episodes (Infant Involvement: free play–teaching, r = .48, p = .0001; Infant

Affect: 1st phase—reunion phase of the SFP, r = .43, p < .0001; Infant Affect: care giving—1st phase of SFP, r = 2.0, p = .05;

care–reunion phase of the SFP, r = .26, p = .015). In addition, infants who showed negative affect during the 1st phase of

the SFP were more likely to show negative affect during the reunion phase (McNemar test for related samples, X2 (1,

N = 87) = 8.04, p < .005); infants who showed negative affect to mothers’ still-face phase were more likely to show negative affect to the stranger (McNemar, X2 (1, N = 93) = 25.41, p < .0001); and infants who showed positive affect to their

mothers’ still-face were more likely to show positive affect to the stranger (McNemar, X2 (1, N = 93) = 33.97, p < .0001).

(2) Intercorrelations between maternal behavior and infant behavior within episodes: Findings show that: (1) Maternal Sensitivity and Maternal Intrusiveness during free play were correlated with Infant Involvement during the same episode

(r = .33, p < .001; r = −.30, p = .004, respectively) and, together, Sensitivity and Intrusiveness accounted for 12.9% of the

variance in Infant Involvement (F(2, 89) = 6.57, p = .002), (2) Maternal Sensitivity and Intrusiveness during the teaching

episode predicted Infant Involvement (r = .54, p < .0001, r = −.22, p = .016, respectively) and jointly explained 30% of the

variance in Infant Affect (F(2, 90) = 19.10, p < .0001), (3) the correlation between mothers’ sensitivity during care giving

and Infant Affect during the care giving episode approached significance (r = .20, p = .057), and (4) there was a significant

relation between mothers’ positive affect and infants’ positive affect during the 1st phase (r = .24, p = .019) and during

the reunion phase of the SFP (r = .25, p = .017).

3.2. Primary analyses

3.2.1. Hypothesis 1: Anxious vs. control dyads during floor episodes and 1st face-to-face play

Tables 3 and 4 show the means and standard deviations of the behavioral composites derived from each floor episode and

the 1st face-to-face interaction by group. Separate multivariate GLM analyses tested for group differences in Maternal Sensitivity across all three floor time-episodes and for group differences in Maternal Intrusiveness and Infant Involvement across

free play and teaching episodes. Results were consistently negative, as were results of exploratory analyses in which Episode

was entered as a between-group factor based on findings of Ginsburg, Grover, Cord, & Ialongo (2006). Exploratory univariate

tests applied to each floor measure, taken separately, also yielded null results. Adding to these negative findings, univariate tests revealed no group differences in infants’ positive affect, matched positive affect, or time-lag-to-synchrony during

the 1st face-to-face interaction; nor did infants’ negative affect during the 1st interaction or lead–lag relations distinguish

between groups.

In fact, the only behavioral measure that discriminated the anxious mothers and controls were related to the notation

“E”, reflecting mothers’ exaggerated responsiveness (during the teaching and free play episodes). Specifically, 61.8% (n = 21)

of the anxious mothers acknowledged, gazed, expressed positive affect, and/or talked in an exaggerated fashion in the free

play and/or teaching episode(s) compared to 37.3% (n = 22) of the control mothers (X2 (1, N = 93) = 5.20, p = .023).

3.2.2. Hypothesis 2: Group differences in affect and coordination before and after the still-face phase

Repeated measures GLMs, with episode as the repeated measure, examined main effects of Episode (across control

and anxious groups), Group, and Episode × Group on measures derived from the 1st face-to-face interaction and reunion

phase of the SFP. Significant main effects of Episode were shown for mothers’ positive affect (1st interaction > reunion,

F(1, 85) = 12.14, p = .001, 2p = .13); infants’ positive affect (1st interaction > reunion, F(1, 85) = 3.90, p = 05, 2p = .03), infants’

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

145

Table 4

Measures based on microanalytic coding of face-to-face interactions, by group.

Play 1

Reunion

Control

Anxious

Control

Anxious

M

SD

M

SD

M

SD

M

SD

Mother affect

Positive

66.66

21.51

67.00

19.53

59.23

23.44

65.53

21.57

Infant affect

Positive

Negative (% infants)

29.85

32.2

18.36

26.48

26.5

20.12

24.23

54.5

18.26

25.48

40.6

19.12

Positive match

Degree of synchrony

Time-lag to synch (s)

18.67

.14

2.33

7.36

.07

1.43

18.90

.12

2.54

9.77

.08

2.01

15.82

.13

2.63

11.82

.05

2.62

17.35

.13

2.56

10.35

.07

2.03

Lead–lag (% dyads)

No peak

Baby leads

Mother leads

Mutual

10.2

11.9

22.0

55.9

8.8

14.7

26.5

50.0

7.3

16.4

20.0

56.4

9.4

21.9

12.5

56.3

Table 5

Percentage of infants who showed positive and negative affect during still-face and

stranger challenges.

% Control

% Anxious

Still-face

Positive

Negative

52.5

45.8

50.0

23.5*

Stranger

Positive

Negative

64.4

30.5

64.7

5.9**

*

**

p < .05.

p < .005.

negative affect (1st interaction < reunion, conditional logit: Wald = 11.30, p < .0001, 97% CI, .12–.54), and Matched Positive

Affect (1st interaction > reunion, F(1, 85) = 4.54, p = .04, 2p = .015). In contrast, none of the variables showed significant Group

and/or Group × Episode interactions, though there were two trends that are worthy of note: (1) a Group × Episode interaction

on Matched Positive Affect (F(1, 85) = 3.33, p = .071, 2p = .04), reflecting a somewhat more robust decline from the 1st faceto-face interaction to the reunion among control dyads compared to anxious dyads, and (2) a parallel Group × Episode

interaction on Infant Positive Affect (F(1, 85) = 3.38, p = .07, 2p = .04) reflecting a more robust decline in smiling among

infants of controls than infants of anxious mothers.

3.2.3. Hypothesis 3: Infants’ affect during still-face and interaction with a stranger

Table 5 displays the percentages of infants that showed positive and negative affect during the still-face phase of the SFP

and stranger episode. As shown, a larger proportion of control infants showed negative affect during the still-face (X2 (1,

N = 93) = 4.54, p = .03) and stranger challenges: (X2 (1, N = 93) = 7.75, p = .005) compared to the infants of anxious mothers.

There were no group differences in the proportion of infants who showed positive affect during either challenge.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed at discerning atypical features of interactions between anxious mothers and their infants.

We also looked for differences in infants’ emotional response to mild challenges. To address these issues, we recruited a

community sample of women and selected those with current, clinical anxiety and excluded women with depression so

to provide a “clean” picture of social interactions between anxious mothers and their infants. To provide a comprehensive

view, we observed different types of mother–infant interactions and examined infants’ responses to two challenges. For

analysis, we derived a broad set of measures from each participant, using time-event coding and global rating scales.

A number of results are worthy of mention. First, we found no evidence for deficits in general maternal sensitivity or intrusiveness, although more anxious mothers than controls behaved in an exaggerated manner during the free play and teaching

episodes. We presume that this distinction reflects the hyperarousal that characterizes most anxiety disorders, although the

finding seems somewhat at odds with previous descriptions of anxious mothers as less engaged with their infants during play

(Murray et al., 2007; also Turner, Beidel, Roberson-Nay, & Tervo, 2003; Woodruff-Borden, Morrow, Bourland, & Cambron,

2002). These differences may reflect variations in the composition of the proband groups or in procedures. Alternatively,

146

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

we might consider mothers’ over- or under-responding as reflecting a common difficulty in emotion regulation (Kaitz &

Maytal, 2005), which is a core feature of affective disorders including anxiety (Rodebaugh & Heimberg, 2008). In any case, as

noted by Murray et al. (2007), the discerning features of dyadic interactions between (low risk) anxious mothers and infants

seem more subtle than those described in many observation studies of depressed mothers and their infants (e.g., review in

Goodman, 2007).

Of particular note, infants in our sample and the infants of mothers with social phobia described by Murray et al. (2007)

seemed less communicative and less emotional during social challenges. In the present study, this was seen in the smaller

proportion of “anxious infants” who showed distress to strangers and to mothers’ still-face, and in Murray et al. (2007),

this was seen in infants’ less positive engagement with a stranger. Interestingly, infants of depressed, high-risk mothers

also have been described as less interactive and less upset when their mothers were inattentive to them (Field et al., 2007;

Hart, Field, Letourneau, & Del Valle, 1998; also see Kiser, Bates, Malsin, & Bayles, 1986) or absent for a short period of time

(Dawson, Klinger, Panagiotides, Hill, & Spieker, 1992; Pelàez-Nogueras, Field, Hossain, & Pickens, 1996). As suggested by

Field et al. (2007), this kind of behavior could reflect flattened affect, inhibition, or avoidance on the part of infants who may

be stressed and stressors related to having an affectively disordered mother. These stressors may include routine exposure

to their mothers’ anxiety-related behavior (Murray et al., 2007) or other stressors like abnormal family functioning (Bögels

& Brechman-Toussaint, 2006) that may be related to having a highly anxious mother.

Before ending, we mention several limitations of the present study. First, the sample size was relatively small, and we

may not have had the power to detect small effect sizes, although medium to large effects should have been detected.2 A

second caveat was that inclusion criteria stipulated that the women in the sample were first-time mothers and married,

and this may limit the generalizability of our findings. Also, the sample was well educated, by the women’s reports. Third,

our episodes may have been too brief or our coding protocols may not have captured behaviors that are related to anxiety,

although we used a broad range and ones that seemed to be good candidates. Fourth, our anxious group was comprised of

women with panic, PTSD, or social phobia, and though these disorders share a component of hyperarousal, it is possible that

variations within the anxious group obscured differences between the anxious group and controls.

Certainly more research is needed in order to understand the social environment of infants of anxious mothers and how

it contributes to the transmission of anxiety from parent to child. For this, it will be important to identify profiles of maternal

behaviors related to specific anxiety disorders, as well as features of behavior that seem to be common to anxiety, in general.

For both these purposes, it seems important to consider new measures and paradigms that are tailor-made for the study of

maternal anxiety as shown by the usefulness of our E notation and of the novel paradigm used by Murray et al. (2007) to pick

up signs of mothers’ social phobia (also see Hock, McBride, & Gnezda, 1989). Best would be if these efforts were embedded

in longitudinal designs that incorporate environmental variables (e.g., review in Rutter, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2006), which may

explain variance in children’s outcome. Finally, certain genes (e.g., short allele variant of the 5 HTT) need to be considered as

significant moderators of the relation between maternal anxiety and children’s behavior/developmental problems, given the

risk associated with some genotypes (Fox et al., 2005; review in Rutter et al., 2006). In short, there is much to be done before

strong conclusions can be made regarding the links between maternal anxiety, maternal behavior, and child development;

and the studies available should be regarded as just the beginning.

As part of these efforts, the present study offers data on the interactive behavior of infants and their anxiety-disordered

mothers, who like many women in this category, were not in treatment or medicated (Tam, Newton, Dern, & Parry, 2002).

In all, the data add to the few available on the behavior of anxiety-disordered mothers and perhaps most important, they

demonstrate again that some children of anxious mothers can be distinguished from children of healthy mothers during

infancy.

Acknowledgements

Marsha Kaitz, Department of Psychology; Hilla Rubin Maytal, Department of Psychology (now at the Department of

Psychology, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel); Liat Bergman, Department of Psychology (now at Department of Psychology, The Academic College of Tel-Aviv-Yaffo, Tel-Aviv, Israel); Noa Devor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology;

David Mankuta, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

This study was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (900/02-34) to the first author. We thank the many students

who recruited, interviewed the mothers, and painstakingly coded the films. We also thank the nurses in the well-baby clinics

who helped us recruit mothers and Dr. Ronit Nirel, Department of Statistics, Hebrew University, who provided statistical

advice. We are indebted to the mothers and infants who participated in the study.

References

Agresti, A. (1996). An introduction to categorical data analysis. New York, NY: John Wiley.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

2

The results of post hoc power analyses suggest that for detecting medium size effects, chi-square tests in hypotheses 1 and 3 had a power estimate of

.82, GLM design in hypothesis 1 had a power estimate of .63, and repeated-measures GLM in hypothesis 2 had a .99 power estimate (G*Power; Erdfelder,

Faul, & Buchner, 1996).

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

147

Als, H., Tronick, E., & Brazelton, T. B. (1979). Analysis of face-to-face interactions in infant–adult dyads. In M. E. Lamb, S. J. Suomi, & G. R. Stephenson (Eds.),

Social interaction analysis: Methodological issues. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barlow, D. H. (2002). Origins of apprehension, anxiety disorders, and related disorders. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.), Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and

treatment of anxiety and panic (pp. 252–291). New York: Guildford Press.

Bates, J. E., Freeland, C. A. B., & Lounsbury, M. L. (1979). Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Development, 50, 794–803.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897.

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J. E., & Erbaugh, J. K. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571.

Blissett, J., Meyer, C., & Haycraft, E. (2007). Maternal mental health and child feeding problems in a non-clinical group. Eating Behaviors, 8, 311–318.

Bögels, S. M., & Brechman-Toussaint, M. L. (2006). Family issues in child anxiety: Attachment, family functioning, parental rearing, and beliefs. Clinical

Psychology Review, 26, 834–856.

Bohlin, G., & Hagekull, B. (1987). “Good mothering”: Maternal attitudes and mother–infant interaction. Infant Mental Health Journal, 8, 352–363.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and Loss New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). Developmental psychiatry comes of age. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 1–10.

Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 3–21.

Clark, G. N., & Seifer, R. (1983). Facilitating mother–infant communication: A treatment model for high risk and developmentally delayed infants. Infant

Mental Health Journal, 4, 67–82.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, 100, 316–336.

Cohn, J. F., & Tronick, E. Z. (1988). Mother–infant face-to-face interaction: Influence is bidirectional and unrelated to periodic cycle in either partner’s

behavior. Developmental Psychology, 24, 386–392.

Crockenberg, S. B., & McClusky, K. (1986). Change in maternal behavior during the baby’s first year of life. Child Development, 57, 746–753.

Dawson, G., Klinger, L. G., Panagiotides, H., Hill, D., & Spieker, S. (1992). Frontal lobe activity and affective behavior of infants of mothers with depressive

symptoms. Child Development, 63, 725–737.

Degnan, K. A., & Fox, N. A. (2007). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology, 19,

729–746.

Erdfelder, E., Faul, F., & Buchner, A. (1996). GPower: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28, 1–11.

Feldman, R. (2003). Infant–mother and infant–father synchrony: The coregulation of positive arousal. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24, 1–23.

Feldman, R., Greenbaum, C. W., Mayes, L. C., & Erhlich, S. H. (1997). Change in mother–infant interactive behavior: Relations to change in the mother, the

infant, and the social context. Infant Behavior and Development, 20, 151–163.

Feldman, R., Greenbaum, C. W., & Yirmiya, N. (1999). Mother–infant affect synchrony as an antecedent of the emergence of self-control. Developmental

Psychology, 35, 223–231.

Field, T., Healy, B. T., Goldstein, S., & Guthertz, M. (1990). Behavior-state matching and synchrony in mother–infant interactions of nondepressed versus

depressed dyads. Developmental Psychology, 26, 7–14.

Field, T., Hernandez-Reif, M., & Diego, M. (2006). Intrusive and withdrawn depressed mothers and their infants. Developmental Review, 26, 15–30.

Field, T., Hernandez-Reif, M., Diego, M., Feijo, L., Yanexy, V., Gil, K., et al. (2007). Still-face and separation effects nondepressed mother–infant interactions.

Infant Mental Health Journal, 28, 314–323.

Field, T., Hernandez-Reif, M., Vera, Y., Gil, K., Diego, M., Bendall, D., et al. (2005). Anxiety and anger effects on depressed mother–infant spontaneous and

imitative interactions. Infant Behavior and Development, 28, 1–9.

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (1996). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis (research version). New York, NY: Biometric

Research.

Forbes, E. E., Cohn, J. F., Allen, N., & Lewinsohn, P. (2004). Infant affect during parent–infant interaction at 3 and 6 months: Differences between mothers

and fathers and influence of parent history of depression. Infancy, 5, 61–84.

Fox, N. A., Nichols, K. E., Henderson, H. A., Rubin, K., Schmidt, L., Hamer, D., et al. (2005). Evidence for a gene–environment interaction in predicting behavioral

inhibition in middle childhood. Psychological Science, 16, 921–926.

Ginsburg, G. S., Grover, R. L., Cord, J. J., & Ialongo, N. (2006). Observational measures of parenting in anxious and nonanxious mothers: Does type of task

matter? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 323–328.

Goodman, S. H. (2007). Depression in mothers. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 107–135.

Grillon, C. (2008). Models and mechanisms of anxiety: Evidence from startle studies. Psychopharmacology, 199, 421–437.

Haley, D. W., & Stansbury, K. (2003). Infant stress and parent responsiveness: Regulation of physiology and behavior during still-face and reunion. Child

Development, 74, 534–1546.

Ham, J., & Tronick, E. (2006). Infant resilience to the stress of the still-face. Annals of New York Academy of Science, 1094, 297–302.

Hart, S., Field, T., Letourneau, M., & Del Valle, C. (1998). Jealousy protests in infants of depressed mothers. Infant Behavior and Development, 21, 137–148.

Hock, E., McBride, S., & Gnezda, M. T. (1989). Maternal separation anxiety: Mother–infant separation from the maternal perspective. Child Development, 60,

793–802.

Isabella, R. A., & Belsky, J. (1991). Interactional synchrony and the origins of infant–mother attachment: A replication study. Child Development, 62, 373–384.

Kaitz, M., & Maytal, H. (2005). Interactions between anxious mothers and infants: An integration of theory and research findings. Infant Mental Health

Journal, 26, 570–597.

Kiser, L. J., Bates, J. W., Malsin, C. A., & Bayles, K. (1986). Mother–infant play at six months as a predictor of attachment security at thirteen months. Journal

of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 25, 68–75.

Kogan, N., & Carter, A. S. (1996). Mother–infant reengagement following the still-face: The role of maternal emotional availability in infant affect regulation.

Infant Behavior and Development, 19, 359–370.

Kopp, C. B. (1989). Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology, 25, 343–354.

Lovejoy, M. C., Graczyk, P. S., O’Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology

Review, 20, 561–592.

Lyons-Ruth, K., Bronfman, E., & Parsons, E. (1999). Maternal frightened, frightening, or atypical behavior and disorganized infant attachment patterns.

Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64(3), 67–96.

Lyons-Ruth, K., Connell, D. B., Zoll, D., & Stahl, J. (1987). Infants at social risk: Relations among infant maltreatment, maternal behavior, and infant attachment

behavior. Developmental Psychology, 23, 223–232.

McElwain, N. L., & Booth-LaForce, C. (2006). Maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress as predictors of infant–mother attachment security.

Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 247–255.

McLeod, B. D., Wood, J. J., & Weisz, R. J. (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology

Review, 27, 55–172.

Moore, G. A., & Calkins, S. D. (2004). Infants’ vagal regulation in the still-face paradigm is related to dyadic coordination of mother–infant interaction.

Developmental Psychology, 40, 1068–1080.

Moore, G. A., Cohn, J. F., & Campbell, S. B. (2001). Infant affective responses to mothers’ still-face at 6 months differentially predict externalizing and

internalizing behaviors at 18 months. Developmental Psychology, 37, 706–714.

Murray, L., Cooper, P., Creswell, C., Schofield, E., & Sack, C. (2007). The effects of maternal social phobia on mother–infant interactions and infant social

responsiveness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 45–52.

148

M. Kaitz et al. / Infant Behavior & Development 33 (2010) 136–148

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (1997). The effects of infant child care on infant–mother attachment security: Results of the NICHD study of

early child care. Child Development, 68, 860–879.

Nicol-Harper, R., Harvery, A. G., & Stein, A. (2007). Interactions between mothers and infants: Impact of maternal anxiety. Infant Behavior and Development,

30, 161–167.

Nover, A., Shore, M. F., Timberlake, E. M., & Greenspan, S. I. (1984). The relationship of maternal perception and maternal behavior: A study of normal

mothers and their infants. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 54, 210–222.

Owen, M. T. (unpublished). The NICHD study of early child care mother–infant interaction scales.

Park, S.-Y., Belsky, J., Putnam, S., & Crnic, K. (1997). Infant emotionality, parenting, and 3-year inhibition: Exploring stability and lawful discontinuity in a

male sample. Developmental Psychology, 33, 218–227.

Pelàez-Nogueras, M., Field, T. M., Hossain, Z., & Pickens, J. (1996). Depressed mothers’ touching increases infants’ positive affect and attention in still-face

interactions. Child Development, 67, 1780–1792.

Reck, C., Hunt, A., Fuchs, T., Weiss, R., Noon, A., Moehler, E., et al. (2004). Interactive regulation of affect in postpartum depressed mothers and their infants:

An overview. Psychopathology, 37, 272–280.

Rodebaugh, T. L., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). Emotion regulation and the regulation and the anxiety disorders: Adopting a self-regulation perspective. In A.

Vingerhoets, & J. Denollet (Eds.), Emotion regulation: Conceptual and clinical issues (pp. 140–149). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Rutter, M. (2005). Environmentally mediated risks for psychopathology: Research strategies and findings. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent

Psychiatry, 44, 3–18.

Rutter, M., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2006). Gene–environment interplay and psychopathology: Multiple varieties but real effects. Journal of Child Psychology

and Psychiatry, 47(3/4), 226–261.

Schore, A. N. (2001). The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health

Journal, 22, 201–269.

Schreier, A., Wittchen, H.-U., Höfler, M., & Lieb, R. (2008). Anxiety disorders in mothers and their children: Prospective longitudinal community study. The

British Journal of Psychiatry, 192, 308–309.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (Eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Stifter, C. A., Coulehan, C. M., & Fish, M. (1993). Linking employment to attachment: The mediating effects of maternal separation anxiety and interactive

behavior. Child Development, 64, 1451–1460.

Swain, J. E., Lorberbaum, J. P., Kose, S., & Strathearn, L. (2007). Brain basis of early parent–infant interactions: Psychology, physiology, and in vivo functional

neuroimaging studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 262–287.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics (3rd Ed.). New York: Harper Collins.

Tam, L. W., Newton, R. P., Dern, M., & Parry, B. L. (2002). Screening women for postpartum depression at well baby visits: Resistance encountered and

recommendation. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 5, 79–82.

Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 25–52.

Tronick, E. Z., Als, H., Adamson, L., Wise, S., & Brazelton, T. B. (1978). The infant’s response to entrapment between contradictory messages in face-to-face

interaction. Journal of Child Psychiatry, 17, 1–13.

Tronick, E. Z., & Cohn, J. F. (1989). Infant–mother face-to-face interaction: Age and gender differences in coordination and the occurrences of miscoordination.

Child Development, 60, 85–92.

Turner, S. M., Beidel, D. C., Roberson-Nay, R., & Tervo, K. (2003). Parenting behaviors in parents with anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41,

541–554.

Warren, S. L., Gunnar, M. R., Kagan, J., Anders, T. F., Simmens, S. J., Rones, M., et al. (2003). Maternal panic disorder: Infant temperament, neurophysiology,

and parenting behaviors. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 814–825.

Weinberg, M. K., Beeghly, M., Olson, K. L., & Tronick, E. (2008). Effects of maternal depression and panic disorder on mother–infant interactive behavior in

the face-to-face still-face paradigm. Infant Mental Health Journal, 29, 472–491.

Weinberg, M. K., & Tronick, E. Z. (1998a). Emotional characteristics of infants associated with maternal depression and anxiety. Pediatrics, 102, 1298–1304.

Weinberg, M. K., & Tronick, E. Z. (1998b). The impact of maternal psychiatric illness on infant development. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 53–61.

Weinberg, M. K. & Tronick, E. Z. (1999). Infant and caregiver engagement phases (ICEP). Unpublished manuscript. Boston, MA: Children’s Hospital and

Harvard Medical School.

Weinberg, M. K., Tronick, E. Z., Cohn, J. F., & Olson, K. L. (1999). Gender differences in emotional expressivity and self-regulation during early infancy.

Developmental Psychology, 35, 175–188.

Wijnroks, L. (1999). Maternal recollected anxiety and mother–infant interaction in preterm infants. Infant Mental Health Journal, 20, 393–409.

Wittchen, H.-U., & Boyer, P. (1998). Screening for anxiety disorders. Sensitivity and specificity of the Anxiety Screening Questionnaire (ASQ-15). British

Journal of Psychiatry, 173(Suppl. 14), 10–17.

Wood, J., McLeod, B. D., Sigman, M., Hwang, W.-C., & Chu, B. C. (2003). Parenting and childhood anxiety: Theory, empirical findings, and future directions.

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 134–151.

Woodruff-Borden, J., Morrow, C., Bourland, S., & Cambron, S. (2002). The behavior of anxious parents: Examining mechanism of transmission. Journal of

Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 364–374.