A comparison of dyadic interactions and coping with still

advertisement

347

The

British

Psychological

British Journal of Developmental Psychology (2010), 28, 347-368

©2OiO The British Psychohsicai Society • ! * — f ^ Society

www.bpsjournals.co.uk

A comparison of dyadic interactions and coping

with still-face in healthy pre-term and full-term

infants

Rosario Montirosso'*, Renato Borgatti', Sabina Trojan^,

Rinaldo Zanini^ Ed Tronick^"*'^

'Department of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Psychiatry and Italian NNNS

Centre for Infant Neurobehavioural Study, Scientific Institute 'E. Medea', Bosisio

Parini (Lecco), Italy

^Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Manzoni Hospital, Lecco, Italy

^Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts, Boston, USA

"•child Development Unit, Children's Hospital Boston, Harvard Medical School,

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

^Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, California, USA

Pre-term birth has a significant impact on infants' social and emotional competence,

however, little is known about regulatory processes in pre-term mother-infant dyads

during normal or stressful interactions. The primary goals of this study were to

investigate the differences in infant and caregiver interactive behaviour and dyadic

coordination of clinically healthy pre-term compared to full-term infant-mother dyads

and to examine pre-term infants' capacity for coping with stress using the face-to-face

still-face paradigm (FFSF). Fifty mother-infant dyads, including 25 pre-term infants and

25 full-term infants were videotaped during the FFSR All infants were 6-9 months ofage

(corrected for gestational age in the pre-term group). Infant and maternal socioemotional expressivity and self-regulatory behaviours were coded and measures of

dyadic coordination {Matching, Reparation Rate, and Synchrony) were calculated. There

were no significant differences in infant and caregiver socio-emotional behaviours

between the two groups and both groups demonstrated the still-face (SF) effect and the

reunion effea. There was a difference in self-regulatory behaviour. Pre-term infants were

more likely than full-term infants to use distancing (e.g., by turning away, twisting, or

arching) from their mothers during the FFSF. Additionally, during the Reunion episode

of the FFSF pre-term infants showed more social monitoring compared to full-term

infants. Regardless of the birth status, the dyads showed less coordination and a slower

rate of reparation during the Reunion episode than during the Play episode. The higher

proportion of distancing in the pre-term group and the increase in social monitoring

* Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Rosario Montirosso, Scientific Institute ' £ Medea', Via don Luigi Monza,

20 - 23842, ßosisio Parini. Lecco, Italy (e-mail: rosario.montirosso@bp.lnf.it).

DOI: 10.1348/026151009X416429

348

R. Montírosso et al.

suggest that even in normal interactions pre-term infants may experience a higher level

of stress and have less capacity for self-regulation compared to the full-terms and that

pre-term infants appear to use a compensatory strategy of increased social monitoring

to cope with the stress of renegotiating the interaction during Reunion. The findings

suggest that pre-term infants have different regulatory and interactive capacities than

full-term infants.

Pre-term birth is considered to have a subtle but potentially significant impact on

infants' social and emotional development (Field, 1987; Lowe, Woodward, & Papile,

2005; Macey, Harmon, & Easterbrooks, 1987; Minde, Whitelaw, Brown, & Fitzhardinge,

1983), In addition, previous studies have found that pre-term infants' have difficulty

regulating their behavioural states (Wolf et al, 2002), less capacity for self-quieting

(Thoman & Graham, 1986), and limited capacities for coping with stress (Als, 1983),

Taken together, these factors, along with others (e,g,, early separation), increase the

risk for abnormal development of the mother-infant relationship in pre-term infant

mother dyads (Feldman, Weiler, Sirota, & Eidelman, 2003; Muller-Nix et al, 2004),

because they are likely to affect the quality and the dyadic coordination of the

interaction (Feldman, 2006; Korja et al., 2008), Although, previous research has found

that prematurity affects mother-itifant synchrony during face-to-face interactions

(Feldman, 2006; Feldman & Eidelman, 2007; Lester, Hoffman, & Brazelton, 1985) little

is known about the quality of dyadic processes such as matching, mismatching, and

reparation in pre-term dyads. Thus, the primary goals of this study were to investigate

differences in interactive behaviour and dyadic coordination of clinically healthy preterm compared to full-term infant-mother dyads as well as pre-term infants' capacity

for coping with stress.

Our thinking was framed by the mutual regulation model (MRM; Gianino & Tronick,

1988; also see Fogel, 1993; Sander, 2000). The MRM argues that the interaction is

organized by a bidirectional exchange of communicative signals that are used by the

infant and the caregiver to coordinate the interaction and to cope with the stress of

inevitable interactive miscoordinations. From this perspective, the quality of the

interaction is determined by the ability of each participant to cope with external

Stressors, regulate his/her emotional states, express communicative messages, and

respond to his/her partner's affective communications and regulatory needs,

Caregivers' behaviour is guided by itifants' expressive displays (e,g,, gaze, facial

expressions, gestures, and vocalizations). In turn, itifant behavioural and affective states

are affected by the expressive displays of the caregiver, Tronick and Gianino (1986)

hypothesized that infants, and especially pre-term infants (Als, 1983; Mouradian, Als, &

Coster, 2000) have limited regulatory capacities and, therefore, need their caregivers'

regulatory scaffolding to maintain affective regulation and cope with interactive stress.

Thus, we expected differences in pre-term infant-caregiver expressivity and interactive

coordination and differences in the pre-term infant's self-regulatory coping capacity

compared to full term infants.

Studies have found that during thefirstyear of life itifants born prior to term compared

to full-term infants are less responsive and attentive, make fewer vocal and affective

signals, are fussier, and have lower scores on the clarity of their social cues

(Crawford, 1982; Crnic, Ragozin, Greenberg, Robinson, & Basham, 1983; McGehee &

Eckerman, 1983), Pre-term infants evidence more negative affect and gaze aversion

Pre-term infants in still-face paradigm 349

during dyadic interactions (Van Beek, Hopkins, Hoeksma, & Samsom, 1994) and they are

more difficult to arouse to an attentive state and tend to avoid social stimulation (Field,

1981). In contrast, pre term infants have been described as relatively competent in their

interactive behaviour (Schermann-Eizirik, HagekuU, Bohlin, Persson, & Sedin, 1997) and

as more responsive to vocal and affective signals (Barratt, Roach, & Leavitt, 1992)

compared to full-terms.

Maternal social sensitivity is another factor influencing the infants' social experience,

socio-emotional development and the infant-mother relationship. When the infantmother interaction is viewed as a process of mutual regulation (Tronick, 1989) and if

pre-term infants are less clear in their affective communicative signals, one would

expect pre-term infants to require more sensitive tuning of maternal emotional

responsivity and regulatory scaffolding to maintain attention and positive affect (Als,

1983). However, research on the expressive behaviour and responsiveness of mothers

of pre-term infants is conflicting. Researchers have found that mothers of pre-term

infants compared to mothers of full-term itifants are more stimulating (Crawford, 1982;

Crnic et al., 1983; McGehee & Eckerman, 1983) and display less sensitivity to their

infants' affective cues (Feldman & Eidelman, 2007; Malatesta, Grigoryev, Lamb, Albin, &

Culver, 1986). On the other hand, compared to mothers of full-term infants, mothers of

pre-terms have been found to be more responsive (Barratt etal., 1992; Greene, Fox, &

Lewis, 1983) and to show better performance on interactive measures (SchermannEizirik etal., 1997). Part of the discrepancy in ñndings may be related to differences in

measurement and definitions.

Mother-infant dyadic regulatory processes have been defined in a number of

different ways in the literature but have not been examined in pre-term dyads. Studies of

full-term mother-infant dyads have focused on mothers' and infants' ability to change

affective or behavioural states in temporal coordination with one another (synchrony),

to share the lead in interaction (bidirectionality) and to share joint attentional, affective,

or behavioural states at the same moment in time (matching; Beebe & Lachmann, 2002;

Cohn & Tronick, 1987; Feldman, Greenbaum, & Yirmiya, 1999; Jaffe, Beebe, Feldstein,

Crown, & Jasnow, 2001; Tronick & Cohn, 1989). However, interactions are not always

smoothly coordinated but are characterized by interactive mismatching (Gianino &

Tronick, 1988). Mismatching occurs when the infant and the mother are in different

behavioural states (e.g., infant looking and smiling at the mother and the mother looking

away with a neutral facial expression). Tronick (1989) has shown that mismatches are

associated with interactive stress and Tronick and Cohn (1989) found that mothers and

infants spend most of their playtime in mismatching states. However, most mismatches

were corrected in the next interactive step. The process of changing from mismatching

to matching states is referred to as reparation (measured as the rate of change between

matching and mismatching). From the perspective of the MRM (Tronick, 1989, 2003)

reparation resolves the interactive stress of a mismatch and is a key interactive process

that affects the development of the infant's sense of trust in the mother, self-regulation

and coping with stress (Feldman, Greenbaum etal., 1999; Tronick, 2004). Based on the

research on pre-term infants and their mothers, we expected that pre-term dyads would

have less matching of their interactive states, fewer reparations and would likely

develop different ways of coping with the stress of mismatching compared to full-terms.

Many other factors also come into play that may disrupt the organization of the

dyadic co-regulatory system. For example, maternal-itifant separation caused by

standard incubator care along with the stress of medical procedures (Anand & Scalzo,

2000; Feldman, Weiler, Leckman, Kuint, & Eidelman, 1999) are among the negative

350

R. Montirosso et al.

sequelae of pre-term birth. These conditions are Ukely to decrease the opportunities

for mothers to act as effective external organizers or regulators of the infant's

socio-emotional and behavioural states (Als et al, 2004; Eckerman, Hsu, Molitor, Leung,

& Goldstein, 1999; Hofer, 1994; Spangler, Schieche, Ilg, Maier, & Ackermann, 1994).

Thus, aversive conditions affecting early caregiving interactions can lower level of

coordination observed between mothers and premature infants during the first 6 months

of life (Feldman & Eidehnan, 2007). For example, in a group of low- to high-risk infants

(3-5 months of age) Lester et al. (1985) found that pre-term infant-mother dyads were

less able to coordinate their behavioural cycles of affect and attention during face-to-face

social exchanges compared to full-term pairs. Feldman (2006) examined Unks between

neonatal biological rhythms (sleep-wake cyclicity and cardiac vagal tone activity) and

the emergence of interaction rhythms (mother-infant synchrony computed from

microanalysis of face-to-face interactions at 3 months of age). She found that high-risk

premature infants displayed disorganized biological rhythms, lower levels of dyadic

synchrony, a more limited capacity for arousal modulation, and lower thresholds for

negative emotionality. Although, the low risk group of pre-term infants did not differ

from the full-term group on the continuous measures of synchrony and neonatal

orientation, they scored significantly more poorly than the full-term group on negative

emotionality and arousal modulation. In contrast, in a recent micro longitudinal study

Korja et al (2008) found that mother-infant interaction was comparable between preterm and full-term infants at 6 and 12 months of age. Perhaps, the differences seen in

younger infants disappear by the second half of the first year of life.

Differences between full-term and pre-term infants in socio-emotional behaviours

(SEB) have been examined during several types of adult-infant interactions: feeding

(Minde et al, 1983; Singer et al, 2003), undressing the infant (Schermann-Eizirik et al,

1997), and face-to-face play interactions, including peek-a-boo (Eckerman, Oehler, &

Medvin, 1994; Forcada-Guex, Pierrehumbert, Borghini, Moessinger, & Muller-Nix,

2006). However, few studies have studied a context that involves interactional stress or

challenge, yet a stress places different demands on the communicative and social

abilities of the infants, mothers, and dyads and may bring out differences not seen in

non-stressful contexts. For example, Malatesta, Culver, Tesman, and Shepard (1989)

recorded face-to-face interaction involving play and separation/reunion sessions in preterm and full-term infants at 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 22 months. They reported that stressful

situations compared to non-stressful situations and that pre-term birth altered infant

affective expressions and maternal contingency levels.

However, almost no studies have specifically addressed pre-term infants' abilities to

coordinate and repair interactions or their emotional regulation during a stressful

situation. This lack of research is in part due to researchers having few paradigms for

examining infants coping with stress in early infancy (Lewis, Hitchcock, & Sullivan,

2004). One paradigm that has been established as a standard method is the face-to-face

still-face paradigm (FFSF; Adamson & Frick, 2003; Troniek, Als, Adamson, Wise, &

Brazelton, 1978). It is well established that the FFSF is a pow^erful paradigm for

examining infants' socio-emotional competence and abuity to cope with stress (for an

overview see, Adamson & Frick, 2003) and several studies have demonstrated that the

effect of the still-face (SF) is robust among different groups of infants, including both

lo-w- and high-risk samples (Adamson & Frick, 2003; Troniek et al, 2005). During the

FFSF paradigm, infants engage in normal face-to-face interaction -with their caregiver and

also confront the perturbation of the caregiver remaining poker-faced and unresponsive

(SF). Thus, the FFSF paradigm allows for the evaluation of both infants and mothers'

Pre-term infants in still-face paradigm

351

affective and regulatory behaviour and dyadic characteristics during normal interaction

(Play episode), infants' coping capacities during the stress of the SF (SF episode), and

their coping and regulation during the resumption of the normal interaction (Reunion

episode), when mothers and infants must re-establish and repair the interaction

following the stress of the SF. During the SF episode, infants show a typical signature

response known as the SF effect (Adamson & Frick, 2003). They show a dramatic

decrease in smiling, more gaze aversion, and an increase in negative affect. In addition,

infants repeatedly attempt to re-engage the adult by smiling and gesturing while looking

at the interaction partner. When these attempts fail, infants show an increase in negative

affect, gazing away, and self-comforting behaviours. Following the SF in the Reunion

episode, infants show an increase in smiling and eye-contact. However, some studies

show that there is a carry-over of negative effect from the SF episode to the Reunion

episode, indicating that the itifants have to cope with the stress from the SF during the

Reunion episode. The carry-over of negative affect has been labelled the reunion effect

(Adamson & Frick, 2003).

To our knowledge, only one study has looked at the pre-term mother-infant pairs using

the FFSF Segal etal. (1995) used it with groups of black pre-term and full-term motherinfant pairs from middle and lower income levels. No differences in negative affect were

found between groups, but pre-term infants spent less time displaying smiles than fullterms. The premature infants showed the SF effect w'tíh a significant reduction in smiling

from Play to the SF episode, confirming that healthy pre-term infants, like full-terms, have

developed expectations about social interactions. Unfortunately, there was no evaluation

of the mothers' interactive behaviour or the dyadic characteristics of the interactions.

This study evaluated the effects of premature birth and interactional context on

mother-infant affective expressiveness and the dyadic features of their interactions.

Since, differences in levels of social engagement and the quality of maternal

responsiveness have been found between premature infants born at low^ and high

medical risk (Greene et al, 1983; Landry, Chapieski, Richardson, Palmer, & Hall, 1990;

Landry, Smith, Miller-Loncar, & Swank, 1998), we chose to assess healthy pre-term

infants with birth weight appropriate for gestational age, normal psychomotor

development, and a documented absence of brain damages. At the time of testing infants

ranged in age from 6 to 9 months (corrected for gestational age in the pre-term group).

Though this is, a wider age range than used in other studies, we did not expect the age

range to affect our results for several reasons. A number of studies have found that after

the age of 6 months, the SF effect and reunion effect become stable (see Adamson &

Frick, 2003). For example, Striano and Rochat (1999) found no significant age effects on

infant behaviour in the FFSF between 7- and 10-month-olds suggesting that ways of

coping become characteristic of the infant by 6 months of age. Mother-infant dyadic

coordination also is very similar at 6 and 9 months of age (Tronick & Cohn, 1989).

Furthermore, by the second half of theirfirstyear of life, pre-term infants have had more

of a chance than younger pre-term infants to get catch-up developmentally with fullterm infants (Brachfeld, Goldberg, & Sloman, 1980).

From the perspective of the MRM and the literature we expected that pre-terms, as

compared to full-term infants, would evidence less social attentiveness, more negative

and fewer positive affects, and fewer self-regulatory behaviours during the FFSF

paradigm. Second, despite the contradictory empiricalfindingsabout the impact of preterm birth on the mothers' SEB, we expected that mothers of pre-term infants would use

different strategies to help their infants regulate affective states compared with mothers

of full-terms because of the expected differences in their itifants' communicative and

352

R. Montirosso et al.

regulatory behaviours. The research, however, does not allow for a more specific

hypothesis about the form of such differences (e.g., more or less maternal interest or

positive affect). Third, we expected that the dyadic organization of the interaction

would be different among pre-term dyads compared to full-term dyads. In line with

previous SF research (Tronick & Cohn, 1989; Weinberg, Tronick, Cohn, & Olson, 1999)

three measures of coordination (i.e., Matching, Reparation Rate, and Synchrony) were

used to assess the mother-infant dyadic processes. We expected that pre-term dyads, as

compared to full-term dyads, w^ould evidence less synchrony (Lester et al., 1985;

Feidman, 2006). Based on the MRM, we also expected that pre-term dyads compared to

full-term dyads would show less matching and fewer reparations of behavioural and

affective states. Fourth, w^e sought to identify some of the factors (gender, birth status,

developmental quotient, level of maternal depressive symptomatology, socio-economic

status (SES), and maternal SEB) associated with infant SEB during SE Regardless of the

extent to which the data support these hypotheses, thefindingsfrom this study will add

to our understanding of the regulatory capacities of pre-term infants and mothers, the

dyadic features of their interaction and the effects of stress on the infant and the mother.

Method

Participants

Fifty mother-infant dyads, 25 healthy pre-term infants (11 females) and 25 full-term

infants (12 females) participated in the study. All the infants were between 6.8 and

99 months of age (corrected for gestational age in the pre-term group). The pre-term

infants were recruited consecutively from all the infants, born between August 2002

and February 2003 in the NICU at 'A. Manzoni' Hospital, Lecco Gtaly), w^ho met the

following criteria: gestational age (GA) less than i6^^^ weeks (range: 26-36 weeks),

birth weight less than 2,500 g (range: 845-2,450 g), and an absence of serious

medical complications (e.g., grade I intraventricular hemorrhage, any degree of

periventricular leukomalacia, any degree of hearing or visual impairments, congenital

abnormalities). Their mothers were excluded if they were at psychosocial risk due to

a history of drug abuse, mental illness, or had high levels of depressive symptoms

(i.e., greater than the cut-off level on the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]; Beck,

Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erlbaugh, 1961). Twenty-eight (93%) of the 30 eligible

mothers of pre-term infants, we contacted agreed to participate. Three pre-terms

were excluded because they became too distressed to complete the experimental

procedures. Two w^ere members of twin pairs.

Healthy full-term participants were recruited during the same time period from a

list of possible full-term infants obtained from community paediatricians. Selection

criteria for control subjects were: full-term gestation (> 37 weeks, GA range: 37-41),

appropriate weight for GA (birth weight > 2,500, range: 2,540-3,840 g), Apgar scores

of at least 7 at 1 min and 8 at 5 min, no congenital abnormalities, and uncomplicated

prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal courses. Their mothers met the same criteria used

for the mothers of the pre-term participants. Twenty-five (71%) of the 35 mothers of

eligible full-term infants contacted agreed to participate. No fuU-term infants were

members of twin pairs. No full-term infants had to be excluded because of distress

during the procedures. The infant and maternal characteristics of both groups are

reported in Table 1. As can be seen, the selection criteria for both groups resulted in

clinically healthy samples.

Pre-term infants in stili-face paradigm

353

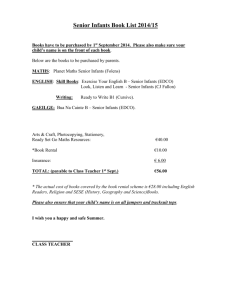

Table I . Infants' and maternal characteristics

Full-term dyads

(N = 25; F = 11)

Characteristics

Infant

G A at birth (v^eeks)

Birth v^^eight (grams)

Age (months)*

Brunet-Lezine score

Maternal

Age (years)

Education (years)

SES

BDI score

Pre-term (dyads

(N = 25; F = 12)

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

39.9

3,293

9,0

101.1

1.2

382

I.I

5.3

32,1

1,516

9.3

100,1

2.8

483

1,2

8,6

33

14.0

68

5.5

4.7

2.9

17.4

3.4

32

12,3

61

4,6

3,6

2,8

23,8

2,4

Note, *GA, gestational age corrected for GA in the pre-term infants; F, female; SES, socio-economic

status; BDI, Beck depression inventory.

Procedure

Mothers of potential participants (pre-terms and full-terms) were recruited by phone.

Participation was voluntary. They were told that the study concerned infant-mother

interactive and communicative behaviour. Mothers who expressed an interest in

participating in the study were scheduled to visit the laboratory of the 'E. Medea'

Scientific Institute at a time when they thought their infants would be rested and alert,

usually between 9 a.m. and noon. The protocol included the video-recording the

mother-infant interaction in the FFSF, completion by the mother of a socio-demographic

questionnaire, a clinical report form, and the BDI, The study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the 'E, Medea' Scientific Institute and written informed consent was

obtained from all the mothers.

Measures

SES

SES was coded according to the information provided by caregivers on the basis of

Hollingshead's (1975) classification for parental occupation.

Developmental quotient

Developmental quotient (DQ) was determined by the Brunet-Lézine's scale (Brunet &

Lézine, 1955), a widely used, standardized measure that provides general indexes of

mental and psychomotor development relative to group norms in itifants aged 4 months

to 5 years. The Brunet-Lezine is based on early descriptive research by Gesell (Gesell &

Amatruda, 1947), It has well-established reliability and validity. The scale evaluates the

child's development in four areas: posture and gross motor function, eye-hand and finemotor coordination, language, and social reactions. Scores above 90 are considered

normal, 80-90 are below average (i,e,, lo'w normal), 70-79 are considered borderline,

and scores below 70 represent some degree of mental retardation.

354

R. Montirosso et al.

Maternai depression

Maternal depression was evaluated with the BDI (Beck etal., 1961). The BDI is a 21-item

measure of depressive symptoms. Items are rated on a four-point rating scale, indicating

the absence/presence and the range of severity of depressed feelings/behaviours/symptoms. The BDI demonstrates good internal consistency and has concurrent and

discriminant validity in clinical and non-clinical samples (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988).

A score of greater than 12 was used as the cut-off for the clinical range (O'Hara, Rehm, &

Campbell, 1983).

Laboratory setting

FFSF interactions

Caregivers and infants were videotaped during the FFSF procedure, based on the

original paradigm developed by Tronick et al. (1978). The video room was equipped

with a high chair, an adjustable sw^ivel stool for the caregiver approximately 40 cm from

the infant, two cameras (one focused on the infant, the other on the caregiver), and a

microphone. The paradigm is made up of three 2 min episodes: (a) a 2 min face-to-face

play interaction (Play); (b) a 2 min SF interaction (SF), and (c) a 2 min reunion play

interaction (Reunion). Prior to the video-recording, the mothers were instructed to play

with their infants during the Play and Reunion episodes just as they would normally do

at home. For the SF, the mothers were instructed to pose a neutral expressionless face to

their infants while looking at them, but not to smile, talk, or touch their infants. The

signals from the two cameras were edited off-line into a video-recorder to produce a

single image with a simultaneous frontal vie'w of the face, hands and torso of the infant

and mother. For analysis purposes, a computerized digital format was created for each

infant-mother dyad's video clip.

Behavioural coding

Infants' and caregivers' behaviours w^ere coded using the infant and caregiver

engagement phases (ICEP; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998; see also Tronick et al., 2005).

The ICEP system is made up of a set of mutually exclusive infant and caregiver phases of

interactive engagement and several additional codes for regulatory behaviours.

Definitions for ICEP and infant self-regulation codes are provided in Table 2. ICEP were

coded in two separate viewings of the videotape. A third viewing of the tape was devoted

to coding infant regulatory behaviours (i.e., self-comforting/mouthing, hand clasping, and

distancing/turning away from the caregiver). The coding was done from the digital video

by coders masked to the pre-term status of the infants. A digital time display was used to

track time intervals and the time code was automatically entered into a datafile.Software

developed by the E. Medea Scientific Institute's Bioengineering Laboratory allowed

coders to indicate the time measured to within 1-s w^hen a particular behaviour occurred.

This coding procedure produced an absolute frequency count of the ICEP codes and

regulatory behaviours and maintained their temporal sequence within a 1-s interval.

Reliability

Inter observer reliability values for both the ICEP and the additional codes were

determined through percentage agreement and Cohen's kappa (Cohen, I960).

Fifty percent of the Play, SF, and Reunion episodes w^ere selected randomly and were

assessed for agreement between two independent coders. The mean percentage of

Pre-tern) infants in still-face paradigm

355

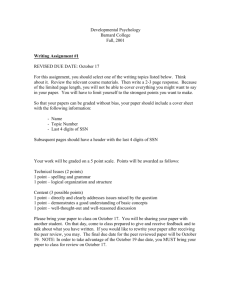

Table 2. Outline of the encoding system of the ICEP (Weinberg & Troniek, 1998).

Infant engagement

Negative engagement: The infant is negative or protesting. The infant displays negative facial

expressions (e.g., sadness, distress, crying, or grinnacing), complaining, being fussy, crying

vocalizations. When the infant is protesting, he/she often displays facial expressions of anger,

grimaces, and fussing/crying.

Withdrawn: The infant is withdrawn and minimally engaged with the caregiver. This phase often

includes sad facial expressions, whimpering vocalizations, slumped posture, and gaze aversion

Object/environment engagement: The infant is looking at objects that are either proximal (e.g., infant

seat) or distal (e.g., camera). The infant may manipulate proximal objects (e.g., infant chair strap;

caregiver's hands)

Social monitoring: Gazing at caregiver's face/eyes with a neutral or interested facial expression.

Infant may vocalize in a neutral manner

Sociai positive engagement Gazing at caregiver's face/eyes while smiling

Caregiver engagement

Negative engagement: The adult is negative, intrusive or hostile

Withdrawn: The adult is minimally engaged and withdrawn with the infant (disengagement from

infant for gaze direction, facial expressions and/or vocalizing)

Non-infant focused engagement: The adult is not attending to the infant and is involved in a

non-infant focused activity

Social monitor: Gazing at infant with neutral/interested expression or with positive vocalizing.

Social positive engagement: Positive affect (smiles, laughter, exaggerated expressions)

Infant self-regulation

Mouthing: Infant sucks on his/her body (e.g., thumb or wrist)

Seif<lasping: The infant's two hands are touching

Distancing: The infant's shoulders and trunk are rotated sideways from the caregiver and the

infant's head is averted

agreement and Cohen's kappa were .85 and .73 for infants' behaviour, .89 and .75 for

caregivers' behaviour, and .88 and .74 for the regulatory codes.

Data reduction and dependent measures

Dependent measures for the infant, caregiver, and dyad were:

(1) The proportion of time the infant or caregiver were in each ICEP phase was

obtained by dividing the total time of each code by the total length of the episode.

(2) The proportion of time for self-regulatory behaviours was obtained by dividing the

total time of each code by the total length of the episode.

(3) Three measures of coordination were analyzed: Matching, Reparation rate,

and Synchrony. Following procedures from previous studies (Troniek & Cohn,

1989; Weinberg et al, 1999), measures of coordination were defined as follows:

(a) Matching: the extent to which caregivers and infants shared joint ICEP codes;

infant and mother simultaneously in Negative, Withdraw^n, Looking a-way, Social

Monitor, or Social Positive states, (b) Reparation Rate: the rate of change between

mismatching to matching states, (c) Synchrony: the extent to w^hich mothers and

infants simultaneously increased or decreased their level of engagement in the

same direction (more or less engagement) w^ith each other. Synchrony is quantified

by first scaling the infant and mother ICEP codes from less to more engaged and

356

R. Montirosso et al.

then calculating the proportion of shared variance at LagO, as indexed by the

square of the cross-correlation between each mother and infant's time series of

mean engagement scale scores. Matching and Synchrony measures differ in that

Matching focuses on the shared or non-shared content of the behaviours of

mothers and infants (they are doing the same thing at the same time), whereas

Synchrony evaluates how mothers and infants change their levels of engagement

with each other over time, regardless of the content of their behaviour (getting

more or less engaged even if they are doing different things). Thus, some dyads

might seldom be in matching states but nonetheless have high-synchrony scores

because they tended to change their level of engagement in the same direction.

Statistical analysis

Pearson correlations were calculated in order to evaluate possible relations between

the infant's age and infant ICEP phases and infant self-regulatory behaviours and

measures of coordination. To assess the effects of group (pre-term vs. full-term) and

interactional context (Play, SF, and Reunion) on infant and maternal ICEP phases

and self-regulatory behaviours, we conducted separate 2 (group) X 3 (episode)

ANOVAs with episodes as repeated measures. For the caregiver, negative engagement,

withdrawn, and non-infant focused engagement were not included in the ANOVA

because of the low proportion of occurrence. Following the techniques used in

previous studies (Tronick & Cohn, 1989; Weinberg etal., 1999), coordination measures

w^ere analyzed as follows: Matching, the adjusted proportions were transformed using

and arcsine transformation' and then examined in a 2 (group) X 2 (episode) ANOVA

w^ith episodes as repeated measures; the Reparation Rate per second was arcsine

transformed and analyzed in a 2 (group) X 2 (episode) ANOVA with the Play and

Reunion play episodes as repeated measures; and Synchrony was evaluated using the

cross-correlations of the Mother and Infant Scale scores in a 2 (group) X 2 (episode)

ANOVA with Play and Reunion play as repeated measures. Because all mothers were

instructed to behave in the same manner during the SF episode, the caregiver and

dyadic variables were analyzed only for the Play and Reunion episodes using a repeated

measures ANOVA. Significant episode effects were evaluated in pair wise comparisons

using post hoc tests w^ith the critical p value for significance adjusted w^ith Bonferroni

correction to control for multiple tests. Effect size was evaluated using the partial Eta

square (Tip), which evaluates the proportion of variance accounted for by each

variable. The conventional cut-offs for T|p = .01, .06, and. 14 for small, medium, and

large effect sizes were used (Green & Salldnd, 2003).

Separate forward stepwise linear regressions were done to identify the significant

predictors of each itifant's SEB (infant ICEP phases and self-regulatory behaviours). The

effect of the following variables were exatnined for each episode of the FFSF procedure:

gender, birth status (full-term or pre-term birth), DQ, BDI scores, and SES. The maximum

number of variables entered into the regression analysis was five, insuring that there

were at least 10 participants for each independent variable (Munro, 1997). All analyses

were performed at a significance level/J < .05.

Recause the dependent variables were expressed as proportions, the data were arcsine transformed. The arcsine

transformation was performed to make the distribution of the variable approximately normal for statistical analysis. Cohen and

Cohen (1983) suggested this transformation for uncorrelating the means and variance of proportional data.

Pre-terw infants in stiii-face paradigm

357

Results

As expected, comparisons (t test) between the full-term and the pre-term groups'

medical and demographic variables revealed that only the infants' GA and birth weight

were significantly different, i(48) = 11.50, p < .001, and i(48) = 12.91, p < 001,

respectively. No associations were found for the correlation of corrected age and DQ.

A chi-square test revealed that gender was not significantly associated with group. There

were no significant differences in age, education, SES, and BDI scores between the

parents of fuU-term and pre-term infants. No significant correlations were found

between the infants' age and infants' behaviour, self-regulation. Matching, Reparation

Rate, or Synchrony. Consistent with findings from previous SF research, these results

suggest that the age range used in the present study w^as not associated w^ith the infant

variables or coordination measures.

Infant and maternal ICEP phases and infant self-regulation

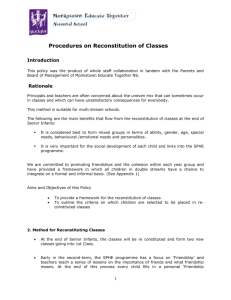

Table 3 presents the adjusted proportion means and SD of infant and maternal ICEP

phases and self-regulatory behaviours for pre-term and full-term infants. Contrary to

expectations, the analysis revealed no significant differences in ICEP codes between

groups across the three episodes for infant and maternal ICEP phases. As expected, a

significant effect was found for self-regulatory behaviours, i='(l,48) = 8.88, p < .01,

T|p = .19. The partial Eta squared level indicates a large effect size (Green & Salkind,

2003): pre-term infants compared to full-term infants showed higher levels of

distancing/turning away (0.10 vs. 0.03, respectively). No differences were found for oral

self-comforting/mouthing and self-clasping.

There were significant differences in infant ICEP phases and self-regulatory

behaviours for the different phases of the EESF: Negative engagement, F(2,86) = 11.63,

p < .00, f]l = .23; Withdrawn, F(_2,86) = 4.80,p < .05, iq^ = .11; Object/environment

engagement, F = (2,86)17.60, p < .001, TI^ = .32; Social monitor, F(2,86) = 4.70,

p < .05, Tip = .11; Social positive engagement, 7^(2,86) = 13.72, p < .001, Tip = .26,

and Distancing/turning away from caregiver, F(2,86) = 6.^0, p < .01, Tip = .14. These

size effects were moderate to large.

As expected, regardless of group membership, a Bonierroni post hoc analysis found

that infants exhibited a greater proportion of negative affect and withdrawn behaviour

during the SE Moreover, there •was an increase in the infant's negative affect in the

Reunion, which did not return to the levels found in the Play episode. In the SE episode

infants also engaged in more self-regulatory behaviours and showed a reduction of Social

Monitoring and Social Positive engagement, both of which returned in the Reunion

episodes to the levels observed in the Play episode. These findings show that both

groups reacted with negative affect to the SF and both had a carry-over effect of negative

affect from the SE into the Reunion episode as well as an increase in positive affect

reflecting the ambivalent nature of the infant's behaviour during the Reunion play. There

was one significant group X episode interaction for Social Monitoring, F(2,86) = 397,

p < .05, Tip = .10. Separate t tests for each episode revealed that during the Reunion

episode, the pre-term dyads showed greater social monitoring than full-term dyads

(respectively, 0.28 vs. 0.17), i(48) = -2.21,p < .05. There were no significant episode

effects (Play vs. Reunion) for the Caregiver Engagement Phases.

The regression analysis evaluating the predictors of infant SEB during the SF

paradigm is presented in Table 4. None of the predictor variables were correlated w^ith

each other at greater than r = .38 indicating little multi-coUinearity. The significant

R. Montirosso et al.

lN00>O

INOIN

OCSci

mnvo

1

<00^

—O

ÖÖ

o ——

O O O

O O O

LOLO

f^. "^

OÖ

(v.)f^|•T^

—O—

O O Ö

<NLo

O O O

mt^

ON — o

ÖÖÖ

ÖÖ

ÖÖÖ

OÖ

ÖÖÖ

Lororo

INOIN

O O O

>o<N

——

O'O

OO —

O O O

O O O

lo-o

ININ

CiO'

— pLO

<~iC>

pop

00 — —

OOO

O

—p ^

ÖÖÖ

<s — .

ÖO

p p p

ÖÖÖ

lo IN -o

w-i CN

rM ~ IN

~ O

I

títítí títí

O

I

O

I

'^'"i

P° —

rviNOO

— OO

OOCi

OO

<N — LO

i^f^

ÖÖ

— p p

ÖÖÖ

ro IN O„

— O —

I '

títítí

L O v O r O l O

—

^~ ^ 3 >O

—^ ^ 3

os — LO

^ 5 ^ 3 ^—

ÖÖÖ

ÖÖ

I I I

"^ ^ i rsj

•^-. ^^

^5 ^^ ^^

rsj fNj

OOO

ÖO

ocio'

ÖÖ

^^

^ ^ ^ ^

^ ^ ^ ^ ¿ ^

l,^ ^ ^

ÖÖ

Ö Ö Ö ÖÖ

^ ^ ^O

^ ^ ^^ ^ ^

^^ f^

^ ^ p^ QQ

—o

O O O

ININ

— O O

^N( P O

ÖÖÖ

00

Po ^ ^

IN~IN

II

Ö Ö Ö

^i ^i ~^

OÖÖ

^ ^ ^^p ^ ^

Ö Ö Ö

títítí títí títítí títí títítí

J:

a.

U

bo

se

-o

c

«

O^ LO fN

^— ^5 LO

Ö Ö Ö

^~ ' ^

fN ^3

OÖ

^3 ^3 ^3

^3 ^3 ^5

Ö Ö Ö

r**» ro

r**» rS

ÖÖ

t*v —~ r o

^3 ^3 ^3

Ö Ö Ö

^O ro Lo

ro ""^ fN

^í* f^

~"^ ^5

^i ^ ^ ^3

^3 ^i ^i

^— •""

fNj rs4

^ ^ •"- r o

••^ ^i

^i

CiCÍO

Ö Ö

ÖO'Ö

Ö Ö

Ö Ö Ö

f*J ^ r o í

00 LO

^3 ^3 C3

r**. fN|

p*>i, ^3 —

rop^

ÖÖÖ

—p

ÖÖ

p p p

ÖÖÖ

f^f^ p p p

ÖÖ Ö Ö Ö

"<O ' O Ov

f Ñ —• rsj

"^ —

— O

Ö Ö Ö

Ö Ö

íN p lO

Ö Ö Ö

— p

Ö Ö

<

(U

-O

tu

-o

3

O

5

tu

c

lU

O)

E

c

P

títítí

00

—

vO

§ §ö

o o

o o

tí o tí

o o

IN

tí

I I

rs| ro

tí

888

IN

IN

tí

O

es

o o

o o

T3

C

IN

O

O

05

02

01

IN

I I I

76

24

a

E

o

o o

.03

.61

2

T3

C

o.

O

,28

,05

E

C

O

t

o

a.

lU

<u

E

T3

C

S)

ve en

rawn

:/envii

358

•5 ,Si.

| z

XI

lU

(U

E o.

L.

•"t'§

tu

>

tu ü

tM) U

o o

u

(J

«_i

S (^ (8 ^

,Í2

5

Pre-terw infants in still-face paradigm

359

predictor was birth status, accounting for 22% of the variance in Distancing during the

Play and accounting for 9% of the variance in Social Monitoring during the Reunion.

Thus, pre-term status was predictive of greater distancing during Play and Social

Monitoring during the Reunion.

Table 4. Linear regression for variables predicting infant SE B during SF paradigm

Episode

Infant behaviour

Predictor

B

Play

Distancing

Birth status

0.07

Reunion

Social monitoring

Birth status

0.13

SEB

0.03

Adjusted« ^ = .22

0.05

Adjusted R^ = .09

ß

0.43*

0.43*

Note. SE B, standard error of B; *f> < .05.

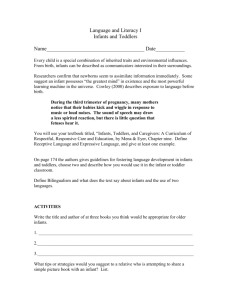

Measures of coordination

The measures of coordination were assessed in the Play and Reunion episodes. Table 5

presents the adjusted proportion means and SD of measures of coordination for preterm and term infants. There w^as no main effect of group for Social Monitor Match and

Social Positive Match. There were significant episode effects. There was a reduction of

Look Away from Partner Match, P(l,46) = 11.43,/» < .01, T|p = .24, during Reunion

(0.23) as compared to Play (0.34) suggesting that dyads of both groups were more

attentive to their partner or looked less at objects after the stressful condition. There

were fewer Total matches states during Reunion (0.30) than during Play (0.40),

F(l,47} = 7.60, p < .01, Tip = .17, suggesting more difficulty in coordination when

dyads resume interaction after the SF episode. There w^as a significant effect for

Reparation Rate between mismatching and matching states suggesting reparation

rate was slower during Reunion (.11 per second) than during Play (.09 per second),

P(l, 47) = 4.10, p < .05, Tip = .09. There was also a significant episode effect for

Synchrony, F(l, 45) = 4.50, p < .04, r\^ = .11. Across the groups, mothers and infants

showed a higher synchrony score during Reunion (0.32) than during Play (0.25),

indicating that after the perturbation of the SF the direction of their changes in

engagement level was more coordinated. The effect sizes were moderate to large (Green

& Salkind, 2003), suggesting that the Reunion episode is a stressful interaction that

requires a complex mutual dyadic adjustment for the mothers and infants.

Discussion

The findings demonstrate similarities as well as differences in the social behaviour,

coping and qualities of dyadic interactions of pre-term and full-term infants and their

mothers. The lack of findings of group differences fails to support the prediction that

pre-terms would be less socially capable and display less social attentiveness, less

positive expressive behaviour and greater negative emotion than full-terms. These

findings are consistent with previous studies that found no differences in interactive SFB

between pre-term and full-term infants in the second half of the first year (Brachfeld

et al., 1980; Schermann-Eizirik et al, 1997). Nonetheless, as we expected based on the

MRM and the literature there appear to be differences in regulatory behaviours between

the groups. Pre-term infants displayed more distancing from their mothers (e.g., by

turning away, twisting, or arching) than full-term infants across all the episodes.

360

R. Montirosso et al.

I

I

~ fN 1^ o ^^ O>

<N o —

I rs

Ö Ö C) ci O O

ro m 0^ O ^ iN

ro — — "^ o rn

I Ö Ö Ö Ö Ö O

00 IN 00 O.

~: -

~

•*

-: O

o o o oo

I

00 ^^ ^O ^^ ^^ 00

rs — IN ro p ro

I Ö Ö Ö Ö Ö Ö

I

I O O O O O

I

I ci Ö O ci O

I

I O Ö Ö Ö Ö Ö

00 "^ ro IN o >O

00 l/^ *O o

O

Lr) o*

O

ro Os rs IN O i/ï

3

T3

o

O

•¡3

'

' ci ci o' o' ci ci

I

I

00 L/^ ro LO O^ NO

, — — — fS p f^

I o o o o o o

o

'c

J

u

<u

-u

3

O- -o 00 — u-i 00

rs o

00 r s I N ON — •<»•

I N r s — ro — I N

I Ö Ö Ö Ö o o

T3

C

o

a

E

Q.

2

n)

ë

1-

p

n)

t

Q.

v2

-5 JZ

i

ii

Q

(1)

td

-F, E

ifli

XI .£ _

u

Q

§

_

XI

Pre-term infants in still-face paradigm

361

In particular, there was greater distancing during Play. The infant's attempts to increase

physical distance from the caregiver are a sign of stress and a failure of self-regulation

(Gianino & Tronick, 1988). Consequently, a greater use of distancing in the pre-term

group may indicate a greater level of stress and a lower capacity for self-regulation

compared to their full-term counterpart even in the normal interactions. This result and

along withfindingsby others (Mouradian et al., 2000; Wolf eí al., 2002) suggests deficits

of self-regulation in pre-term infants during the first year of life.

Interestingly, pre-term infants also evidenced more social monitoring than full-term

dyads in the Reunion episode subsequent to the stress of SF and prematurity was a

significant predictor of social monitoring during the Reunion. These findings suggest

that pre-term infants may try to deal with the stress of the Reunion with the

compensatory strategy of increasing their social monitoring, a less aroused state than

either positive or negative affective states (Greene et al., 1983; Weinberg & Trotiick,

1997). In other words, they use an other-directed strategy (Gianino & Tronick, 1988) in

an attempt to obtain regulatory support from the adult to modulate their stress because

their own self-directed regulatory mechanisms are inadequate. It should be noted that

the differences found here were not associated to gender, developmental quotient, level

of maternal depressive symptomatology, SES, or maternal SEB. These findings suggest

that these low-risk pre-term infants do not have comparable emotional regulatory

functions to their full-term peers and it may be important to monitor their negative

affect, regulation, arousal, and stress reactivity especially in stressful environments in

order to facilitate their optimal development (Feldman, 2006).

Pre-term infants, like full-term infants, displayed the SF effect: more negative affect and

withdra'wn behaviour, less social and positive engagement, and an increase in distancing

from the caregiver in the SF episode than in the Play episode. These results are in partial

disagreement with the study by Segal et al. (1995). They found no differences in negative

affect between pre-term and full-term infants, but also reported that pre-term infants

spent proportionally less time displaying smiles than full-terms. This difference may be

due to methodological differences. Their coding scheme for positive affect may have been

more sensitive than the coding scheme used in this study, whereas the coding scheme for

negative affect was similar (Segal et al., 1995). There was also a reunion effect (Weinberg

& Tronick, 1996) for both groups: the pre-term as well as the full-term infants displayed an

increase in negative affect, less interest in objects and the environment, a decreased

distancing from the caregiver and the prototypical rebound of social positive

engagement. These results confirm Weinberg and Tronick's (1996) hypothesis that the

process of reparation in the Reunion episode is a stressful and complex task for the infants

because of the ongoing effects of the SF experience and the resumption of positive

interaction. Thefindingof SF and reunion effects for the pre-term infants attest to their

capacity to form social expectations, their sensitivity to stress and their capacities for

coping with stress; that is it speaks to social emotional and regulatory Wellness.

Several studies suggest that in thefirstyear of life mothers of pre-term infants are less

responsive to infants' signals than mothers of full-term infants (Harrison, 1990; Harrison

& Magill-Evans, 1996). By contrast, other studies have found that mothers of pre-term

infants are particularly responsive to their infants' affective signals (Barratt etal, 1992)

and several reported that they may actually exhibit more over stimulating behaviour

(Brown & Bakeman, 1980; DiVitto & Goldberg, 1979; Field, 1979). The results of the

present study do not support the findings of either greater or lesser responsiveness of

mothers of pre-terms compared to mothers of full-terms. Mothers of both pre-terms and

full-terms had similar levels of social monitoring and positive affect. Specifically, in both

362

R. Montírosso et al.

groups the mothers' gaze was focused on their infants' or their infants' activities and the

mothers expressed positive affect (e.g., by vocalizations, motherese, making kissing, or

clicking sounds, and singing) at similar levels. These findings are consistent with

previous research in which mothers of pre-term infants were described as relatively

competent in their interactive behaviour with their infants (Schermann-Eizirik et al.,

1997; Stjernqvist & Svenningsen, 1990). Our results on maternal behaviour are

consistent with the evidence that the differences in maternal social behaviour, observed

in the first 6 months of life between the pre-term and full-term groups, tend to fade

during the second half of thefirstyear of age (Brachfeld et al., 1980). It seems likely that

in the second 6 months of life, full-term as well as pre-term infants' behaviours (e.g.,

social skills) tend to consolidate and mothers' adjustment to their infants, as well as their

increased experience with them may overcome stressful factors such as anxiety about

the infants' health and concerns about depression. Consequently, similar tofindingsby

Landry, Chapieski, & Schmidt (1986), our results suggest that maternal adaptation to

pre-term infants tends to be more appropriate towards the end of the first year of life.

This interpretation is further supported by the lack of differences between the groups

on the three measures of coordination (Matching, Synchrony, and Reparation Rate).

These results were not expected. Previous findings suggested that pre-term dyads show

lower levels of synchrony. However, previous research (Eeldman, 2006; Feidman &

Eidelman, 2007; Lester etal., 1985) quantified social interaction during thefirst6 months of

life (3-5 months). In home observational research. Watt (1986) reported that at 3 months of

age, pre-term dyads had lower levels of interaction and synchrony in comparison with their

full-term counterparts but by 6 months ofage the pre-term dyads showed higher levels of

simultaneous interaction, mutual gaze and were more synchronized than full-term dyads.

Thus, it is possible that, in spite of the differences between full-term and pre-term dyads in

their first months of life, the mutual regulatory capacities of the pre-term become more

effective during the second half of the first year of life, and the quality of interaction

becomes comparable between the two groups (Korja et al., 2008). Ourfindingindicated

that overall for both groups, mother-infant synchrony showed a mean value of 0.09, which

is consistent with earlierfindings.Tronick and Cohn (1989) found that at 6 and at 9 months

ofage, synchrony varied from 0.09 to 0.23 for different mother-infant pairs and Weinberg

etal. (1999) reported a mean value of 0.08. Thus, our results suggest that from 6 months of

age, pre-term dyads may be able to synchronize their engagements in a similar way of fullterm dyads. With regard to Matching and Reparation Rate thefindingsof current study

suggest that pre-term infants and their mothers maintained levels of mutual engagement

and reparation similar to those of full-term dyads. In line with previous studies of this age

range (Cohn & Tronick, 1989), the dyads of both groups spent most of their interaction time

in mismatching states (more than 60%). Withdrawn behaviour and negative match were

extremely rare (less than 1%) while social monitor and positive match occurred on average

about 17% and 15% of the time. Furthermore, for both groups the data indicated that the

dyads spent most of the time in a Look Away from Partner Match (25% and 33%,

respectively). Both mother and infant looked at objects that were either proximal (e.g.,

infant seat) or distal (e.g., light switch). This result suggests that the partners are not only

interested in the dyadic context, but also clearly show other behaviours, oriented 'outside

the relationship'. A possible explanation for this result is that the behaviours refiect the

infant's growing interest in objects and that the dyadic focus on other objects is a positive

developmental change (Feidman, 2007). For example, between 3 and 9 months of age,

episodes of shared gaze decrease to about a third of the time while shared attention to

objects increases dramatically (Landry, 1995).

Pre-term infants in still-face paradigm 363

In this study, the mean reparation rate across the groups was 0,09 per second. This

finding is consistent with Weinberg etal.'s (1999) study, which reported a 0,10 reparation

rate during normal face-to-face interactions at 6 months of age. Thus, in both studies, the

repair rate was about once every 10 s, suggesting that reparations are typical features of

the interaction. Consistent with the theoretical perspective of the MRM, these findings

confirm that in pre-term and full-term dyads, interactions are organized into a matching

and mismatching pattern with reparations resolving the mismatches (Tronick, 1989),

As this mismatch-repair-match organization is similar in both groups, it appears that from

6 months of age neither healthy pre-term infants nor their mothers are compromised in

their capacity to coordinate face-to-face interactions, even when they had to deal with a

stressful condition (i,e,, the SF), Thus, our results on coordination suggest that a favourable

infant-mother relationship may function to attenuate the effects of prematurity on early

socio-emotional delays and/or that healthy pre-term infant dyads are able to achieve a

normal quality of interactive regulation in the second half year of life.

Another sign of the normalcy of these pre-term infants was that, as in the fullterm group, the amount of shared engagement (Total matches) decreased in the

reunion play compared to the first play As has been argued by Weinberg and

Tronick (1996), it is likely that after the stress of the SF, both infants and mothers

find it more difficult to coordinate their social behaviour and maintain mutual

engagement. This is corroborated by the finding that the rate of reparations was

slower during Reunion than during the first play interaction. The finding suggests

that mothers and infants made fewer attempts at reparation during Reunion than

during Play and/or found it more difficult to make repairs of mismatching states.

These data appear to be compatible with interpretations suggesting that the

processes of reparation and mutual regulation are more stressful and complex in the

Reunion episode than in the Play episode preceding the SF (Kogan & Carter, 1996;

Weinberg & Tronick, 1996), Dyads showed a higher synchrony score during the

Reunion episode than in the first play, suggesting that after the SF perturbation these

mothers and infants were more sensitive or vigilant to changes in each other's

engagement. Thus, while synchrony and matching are often seen as measuring

similar phenomena they may not be, A higher synchrony score may indicate that the

dyads tracked each other's behaviour more carefully whereas a lower matching

scores may indicate that they are less able to coordinate their behaviours

successfully. In this perspective, a higher level of synchrony may be indicative of

reduced flexibility in interaction (Tronick & Cohn, 1989) and suggestive of greater

dyadic effort to create more predictability in the interaction (Jaffe et al, 2001),

Thus, while synchrony is typically thought of as an indication of a 'good' interaction

(Stern, 1985), it may actually be a measure of hypervigilance, possibly being used as

a strategy for renegotiating the interaction after a stress. In summary, the lack of

group differences indicates that the pre-term infant-mother dyads reacted typically

to the additional stress of the Reunion episode.

There are several limitations in the present study. The sample size though typical for

many micro analytic studies of interactions is relatively small. The pre-term infants w^ere

relatively healthy so the results cannot be generalized to more at-risk populations of

infants. Replications with a larger sample and greater variations of SES and health status

are needed. The study did not follow-up these infants so that we cannot assess the

relations between the differences in regulatory behaviours and later outcome. It would

also be interesting to have other measures of stress (e,g,, skin conductance. Ham &

Tronick, 2008) on the infants and mothers.

364

R. Montirosso et al.

Nevertheless, the results from this study suggest that it is important to evaluate preterm infants and their mothers in different interactive contexts (normal vs. stressful

conditions) and to obtain measures of their coordination in addition to measures of each

partner's interactive behaviours in order to obtain a better understanding of the

mother-infant interaction. The pre-term infant-mother dyads were able to coordinate

their interactions in a similar manner to full-term dyads. Pre-term dyads also

demonstrated similar capacities for the reparation of interactive matches, which

suggests that pre-term infants experience normal levels of reparation. Thesefindingson

coordination and reparation, along with the findings on the typicality of the pre-terms'

reaction to the SF, demonstrate the coping and social competence of the pre-term

infants and their mothers. In the MRM it is argued that reparation is one of the primary

mechanisms underlying normal development, including the development of trust and

attachment, mastery, the experience that negative affect or stress can be transformed

into positive affect and the elaboration of coping capacities (Tronick, 1989, 2007). The

social competence observed in these healthy pre-term itifant-mother dyads suggests

that their interactive experience is typical and likely to lead to positive developmental

outcomes. These findings can be used clinically to reassure parents, which can further

reduce their anxiety and consequently improve their interaction with their pre-term

infant. A technique may be to explain to parents that miscoordination and mismatching

in their interactions with their itifants is normative along with the value of reparation for

their infants' development. Understanding the importance of the inherent messiness of

interactions may help parents overcome their search for the perfect, wished-for

interaction (Brazelton, 1999) which only serves to make them anxious when the fail to

achieve it. Clinicians also need to see reparation and miscoordinations as normal

interactive processes. Indeed, the findings suggest that the clinician can expect pre-term

infant-mother pairs to be interacting w^ell by 6 months of age, but 'well' must be seen as

involving interactive mismatches and reparations as indicators of normalcy and not as

indicators of something going awry and requiring intervention (Trotiick, 2007).

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by funds from the Italian Health Minister (Ricerca Corrente 2003),

partially supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Chiesi Farmaceutici, and from grants

from the National Institute Child Health & Human Development (R01HD37138 & RO1HDO5O459;

E. T, PI) and the National Science Foundation (NSF 06-511; E. T., PI). The authors wish to thank

the nursing and neonatology staff from the nurseries of the Manzoni Hospital NICU (Lecco) and

community pediatricians in Lecco for their support. We thank Patrizia Cozzi for their support in

the data collection. We also wish to thank Sara Averna, Gloria Mauri, Sonia Monticelli, Viviana

Sabadini, Elisa Zoboli for their help in data coding; when the research was conducted they were

graduate psychology students at the Catholic University of Milan. Furthermore, we are grateful to

Carlo Magni from Scientific Institute Medea's Bioengineering Laboratory for the software and the

computer program used for the video analyses. Thanks are due to Dr Uberto Pozzoli for his

support in the matching analyses. Finally, special thanks go to all infants and their mothers

participating in this study.

References

Adamson, L. B., & Frick, J. E. (2003). The still-face: A history of a shared experimental paradigm.

Infancy, 4(4), 451-473.

Pre-term infants in still-face paradigm

365

Als, H. (1983). Infant individuality: Assessing patterns of very early development. In J. D. Call,

E. Galenson, & R. L. Tyson (Eds.), Frontiers of infant psychiatry. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Als, H., Duffy, E H., MeAnulty, G. B., Rivkin, M. J., Vajapeyam, S., Mulkern, R. V, etal (2004). Early

experience alters brain function and structure. Pediatrics, 113(/î), 846-857.

Anand, K. J., & Scalzo, E M. (2000). Can adverse neonatal experiences alter brain development and

subsequent behaviour? Biology of the Neonate, 77(2), 69-82.

Barratt, M. S., Roach, M. A., & Leavitt, L. A. (1992). Early channels of mother-infant

communication: Preterm and term infants./oMma/ of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and

Allied Disciplines, 33(7), 1193-1204.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of Beck depression

inventory: TWenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8(1), 77-100.

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erlbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for

measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561-571.

Beebe, B., & Lachmann, E M. (2002). Infant research and adult treatment: Co-constructing

interactions. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

Brachfeld, S., Goldberg, S., & Sloman, J. (1980). Parent infant interaction in free play at 8 and

12 months: Effects of prematurity and immaturity. Infant Behaviour and Development, 3(1),

289-305.

Brazelton, T. B. (1999). How to help parents of young children: The touchpoints model.Joumal of

Perinatoiogy, 19(6), 6-7.

Brown, J., & Bakeman, R. (1980). Relationships of human mothers with their infants during the

first year of Ufe. In R. Bell & W. Smotherman (Eds.), Maternal influences on eariy behaviour

(pp. 437-447). New York: Spectrum.

Brunet, C, & Lézine, I. (1955). Échelle de développement psychomoteur de tapremière enfance.

Manuel d'instructions. [Scaie of the psychomotor deveiopment of early childhood.

Instruction Manual]. Clamart, France: Éditions Scientifiques et Psychotechniques.

Cohen, J. (I960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educationai and Psychoiogicai

Measurement, 20(1), 37-46.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Appiied regression/correiation analysis for behavioural sciences

(2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cohn, J. E, & Troniek, E. Z. (1987). Mother-infant face-to-face interaction: the sequence of dyadic

states at 3-6 and 9 months. Developmental Psychology, 23, 68-77.

Crawford, J. W. (1982). Mother-infant interaction in premature and full-term infants. Child

Development, 53('i), 957-962.

Crnic, K. A., Ragozin, A. S., Greenberg, M. T., Robinson, N. M., & Basham, R. B. (1983). Social

interaction and developmental competence of preterm and full-term infants during the first

year of life. Child Development, 54(5), 1199-1210.

DiVitto, B., & Goldberg, S. (1979). The effects of newborn medical status on early parent-infant

interaction. In T. M. Eield, A. M. Sostek, S. Goldberg, & H. H. Shuman (Eds.), Infants bom at

risk (pp. 311-332). New York, NY: Spectrum Books.

Eckerman, C. O., Hsu, H. C, Molitor, A., Leung, E. H., & Goldstein, R. E (1999). Infant arousal in an

en-face exchange with a new partner: Effects of prematurity and perinatal biological risk.

Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 282-293.

Eckerman, C. O., Oehler, J. M., & Medvin, M. B. (1994). Premature newborns as social partners

before term age. Infant Behaviour and Development, 17(\), 55-70.

Eeldman, R. (2006). Erom biological rhythms to social rhythms: Physiological precursors of

mother-infant synchrony. Developmental Psychology, 42, 175-188.

Eeldman, R. (2007). On the origins of background emotions: Erom affect synchrony to symbolic

expression. Emotion, 7(3), 601-611.

Eeldman, R., & Eidelman, A. 1. (2007). Maternal postpartum behavior and the emergence of infantmother and infant-father synchrony in preterm and full-term infants: The role of neonatal

vagal tone. Developmental Psychobiology, 49, 290-302.

366

R. Montirosso et al.

Feldman, R., Greenhaum, C. W., & Yirmiya, N. (1999). Mother-infant affect synchrony as an

antecedent of the emergence of self-control. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 223-231.

Feldman, R., Weiler, A., Leckman, J. F., Kuint, J., & Eidelman, A. I. (1999). The nature of the

mother's tie to her infant: Maternal bonding under conditions of proximity, separation, and

potential loss, foumal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(6), 929-939.

Feldman, R., Weiler, A., Sirota, L., & Eidelman, A. I. (2003). Testing a famUy intervention

hypothesis: The contribution of mother-infant skin-to-skin contact (kangaroo care) to family

interaction, proximity and touch, foumal of Family Psychology. 17iV), 94-107.

Field, T. M. (1979). Interaction patterns of preterm and term infants. In T. M. Field, A. M. Sostek,

S. Goldberg, & H. H. Shuman (Eds.), Infants bom at risk (pp. 333-356). New York, NY:

Spectrum Books.

Field, T. M. (1981). Infant arousal, attention, and affect during early interactions. In L. P. Lipsitt &

C. Rovee-Collier (Eds.), Advances in infancy research (Vol. 1, pp. 57-100). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Field, T. M. (1987). Interaction and attachment in normal and atypical infants, foumal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(6), 853-859.

Fogel, A. (1993). Developing through relationships. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Forcada-Guex, M., Pierrehumbert, B., Borghini, A., Moessinger, A., & MuUer-Nix, C. (2006). Early

dyadic patterns of mother-infant interactions and outcomes of prematurity at 18 months.

Pediatrics, 118(1), 107-114.

Gesell, A., & Amatruda, C. S. (1947). Developmental diagnosis (2nd ed.). New York: HoeberHarber.

Gianino, A., & Tronick, E. Z. (1988). The mutual regulation model: The infant's self and interactive

regulation and coping and defense capacities. In T. Field, P. McCabe, & N. Schneiderman

(Eds.), Stress and coping (Vol. 2, pp. 47-68). HiUsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Green, S. B., & Salkind, N. J. (2003). Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and

understanding data (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Greene, J. G., Fox, N. A., & Lewis, M. (1983). The relationship between neonatal characteristics

and three-month mother-infant interaction in high-risk infants. Child Development, 54(5),

1286-1296.

Ham, J., & Tronick, E. (2008). A procedure for the measurement of infant skin conductance and its

initial validation using clap induced startle. Developmental Psychophysiology, 50(6),

626-631.

Harrison, M. J. (1990). A comparison of parental interactions with term and preterms infants.

Research in Nursing and Health, 73(3), 173-179.

Harrison, M. J., & Magill-Evans, J. (1996). Mother and father intemctions over the first year with

term and preterm infants. Research in Nursing and Health, 19(6), 451-459.

Hofer, M. A. (1994). Hidden regulators in attachment, separation, and loss. Monographs of the

Society for Research in Child Development, 55(2-3), 192-207.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). Pour-factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University,

Department of Sociology, Unpublished manuscript.

Jaffe, F, Beebe, B., Feldstein, S., Crown, C. L., & Jasnow, M. D. (2001). Rhythms of dialogue in

infancy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 66, 1-151.

Kogan, N., & Carter, A. S. (1996). Mother-infant reengagement following the still-face: The role of

maternal emotional availability in infant affect regulation. Infant Behaviour and

Devetopment, 19(5), 359-370.

Korja, R., Maunu, J., Kirjavainen, J., Savonlahti, F., Haataja, L., Lapinleimu, H., et al. (2008).

Mother-infant interaction is influenced by the amount of holding in preterm infants. Early

Human Development, 84(4), 257-267.

Landry, S. H. (1995). The development of joint attention in premature low birth weight infants:

Effects of early medical complications and maternal attention-directing behaviors. In C. Moore

& P J. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention: Its origins and role in development. Hülsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Pre-term infants in stiii-face paradigm 367

Landry, S. H., Chapieski, M. L., & Schmidt, M. (1986). Effects of maternal attention-directing

strategies on preterms' response to toys. Infant Behaviour and Development, 5(4), 257-269.

Landry, S. H., Chapieski, M. L., Richardson, M. A., Palmer, J., & Hall, S. (1990). The social

competence of children born prematurely: Effects of medical complications and parent

behaviors. Child Development, 61(5'), l605-l6l6.

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Miller-Loncar, C. L., & Swank, P. R. (1998). The relation of change in

maternai interactive style to the developing social competence of full-term and preterm

chUdren. Child Development, 69, 105-123.

Lester, B. M., Hoffman, J., & Brazelton, T. B. (1985). The rhythmic structure of mother-infant

interaction in term and preterm infants. Child Development, 56(V), 15-27.

Lewis, M., Hitchcock, D. F. A., & Sullivan, M. W. (2004). Physiological and emotional reactivity to

learning and frustration. Infancy, 6(1), 121-143.

Lowe, J., Woodward, B., & Papüe, L. A. (2005). Emotional regulation and its impact on

development in extremely low birth weight infants. Joumal of Developmental and

Behavioural Pediatrics, 26(5), 209-213.

Macey, T. J., Harmon, R. J., & Easterbrooks, M. A. (1987). Impact of premature birth on the

development of the infant in the famäy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(6),

846-852.

Malatesta, C. Z., Culver, C, Tesman, J. R., & Shepard, B. (1989). The development of emotion

expression during the first two years of life. Monographs for the Society of Research in Child

Development, 54, 1-2.

Malatesta, C. Z., Grigoryev, P, Lamb, C, Albin, M., & Culver, C. (1986). Emotion socialization and

expressive development in preterm and full-term infants. Child Development, 57(2), 316-330.

McGehee, L. J., & Eckerman, C. O. (1983). The preterm infant as a social partner: Responsive but

unreadable. Infant Behaviour and Development, 6(4), 461-470.

Minde, K., Whitelaw, A., Brown, J., & Fitzhardinge, P (1983). Effect of neonatal complications in

premature infants on early parent-infant interactions. Developmental Medicine and Child

Neurology, 25(6), 763-777.

Mouradian, L. E., Als, H., & Coster, W. J. (2000). Neurobehavioural functioning of healthy preterm

infants of varying gestational ages. Developmental and Behavioural Pediatrics, 21(6),

408-416.

MuUer-Nix, C, Eorcada-Guex, M., Pierrehumbert, B., Jaunin, L., Borghini, A., & Ansermet, E

(2004). Prematurity, maternal stress and mother-child interactions. Early Human

Development, 79(2), 145-158.

Munro, B. (1997). Statistical methods for health care research. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott.

O'Hara, M., Rehm, L. P, & Campbell, S. B. (1983). Postpartum depression: A role for social network

and life stress variables. The Joumal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 171(6), 336-341.

Sander, L. W. (2000). >XTiere are we going in thefieldof infant mental health? Infant Mental Health

Joumal, 21(1-2), 3-20.

Schermann-Eizirik, L., Hagekull, B., Bohlin, G., Persson, K., & Sedin, G. (1997). Interaction