power of education - Šiaulių universitetas

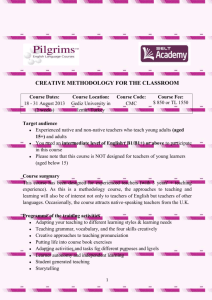

advertisement