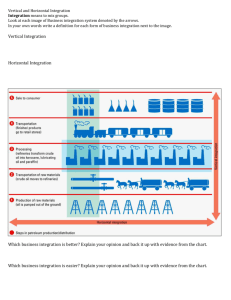

the novel approach of the cjeu on the horizontal

advertisement