Expert Review: Examination of a Hernia

advertisement

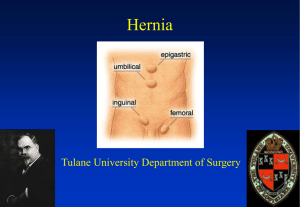

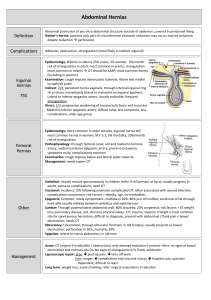

Expert Review Examination of Groin Hernias Laurence Toms*, Sam Mathew Lynn† and Ashok Handa # …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. The Journal of Clinical Examination 2011 (11): 32-43 Abstract Examination of groin hernias is an important skill for medical students and doctors. This article presents a comprehensive, concise and evidence-based approach to examination of groin hernias which is consistent with The Principles of Clinical Examination [1]. We describe the signs seen with groin hernias and, based on a review of the literature, the precision and accuracy of these signs is discussed. Word Count: 2543 (excluding tables, figures, references and abstract). Key words: Hernia examination, Clinical examination, Inguinal hernia, Femoral hernia. Address for correspondence: laurence.toms@doctors.net.uk Author affiliations: * Final Year Medical Student, University of Oxford. † Final Year Medical Student, University of Bristol. # Clinical Tutor in Surgery and Consultant Surgeon, University of Oxford and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Introduction A hernia is the protrusion of tissue through the wall of the cavity in which it is normally contained. Common types of abdominal and groin hernias are listed in Table 1. This article describes the approach to clinical examination of suspected groin hernias (inguinal and femoral) in adults. It does not describe the examination of other abdominal wall hernias. The aim of the examination is to characterise the lump and to make a diagnosis and differential diagnosis. It is important to note that the differential diagnosis includes pathologies which are not hernias but maybe mistaken for them. The relative frequencies of different types of hernia are difficult to estimate and estimates are largely based on registry data of operative management – hence they underestimate those types of hernia that are more often conservatively managed. See Table 1. Background - Review of relevant anatomy Inguinal hernias The inguinal canal is a passage formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique, internal oblique and transversalis fascia. The passage runs from the deep inguinal ring (in the transversalis fascia) to the superficial inguinal ring (in the external oblique fascia). The inguinal canal contains the spermatic cord (Figures 1 and 2) in men, which runs from the abdominal cavity to the scrotum. In women, where the canal is smaller, it contains the round ligament of the uterus. The ilioinguinal nerve also runs through the inguinal canal in both sexes. The inguinal canal traditionally is thought of as having four borders; inferior, superior, anterior and posterior. The anatomy is shown in Figure 2. The inferior border of the canal (often called the floor) is the inguinal ligament (formed from the external oblique aponeurosis). The anterior wall is mainly formed by the external oblique aponeurosis, with the lateral part reinforced by fibres of the internal oblique. The medial end of the external oblique aponeurosis forms the superficial ring. The posterior wall is formed by the transversalis fascia): at the lateral end of this is the deep inguinal ring and at the medial end is the insertion of the conjoint tendon, where the inferior borders of the transversalis and internal oblique apnoneuroses fuse and join to the pubis. The superior border (often called the roof) is formed from this conjoint tendon. 32 Figure 1 Photographs taken during surgical repair of a hernia showing the anterior view of (a) the left spermatic cord within the inguinal canal. Figure 1 (b) the exposed spermatic cord Figure 1 (c) The completed mesh repair just prior to closure. The deep inguinal ring and Hesselbach’s triangle are weak points in the abdominal wall and are thus predisposed to hernias. In an indirect inguinal hernia, abdominal contents move through the deep inguinal ring, down the inguinal canal to the superficial ring and hence become extra abdominal. A direct inguinal hernia moves directly through a defect in the transversalis fascia and may or may not pass through the superficial ring. For the purposes of clinical examination it is important to understand how surface anatomy relates to this underlying anatomy. The inguinal ligament runs from the pubic tubercle to the anterior superior iliac spine (see Figure 3a and 3b). The deep ring is immediately superior to the mid point of this ligament (see Figure 4) and the superficial ring is superio-medial to the junction of the ligament with the pubic tubercle. The mid point of the inguinal ligament should not be confused with the mid point of the inguinal line (called the mid-inguinal point), which runs from the pubic symphysis to the anterior superior iliac spine. The mid-inguinal point marks the femoral artery, which is medial to the deep ring. The Inferior epigastric artery originates from the femoral artery, which is important in defining the borders of Hesselbach’s triangle. 33 its medial border is particularly sharp-edged (formed by the lacunar ligament), meaning that femoral hernias are especially prone to irreducibility and strangulation. Figure 2 The anatomy of the right inguinal canal showing (a) the bony pelvis with the inguinal ligament Figure 2 (c) the superficial ring with the external oblique muscle and aponeurosis in place Figure 2 (b) the deep inguinal ring with the external oblique muscle and aponeurosis removed Femoral hernias A femoral hernia occurs when abdominal contents pass through the femoral canal (see Figure 5). This space, which usually only contains a few lymph nodes, is the medial compartment of the femoral sheath. The inguinal ligament is the superior border, the femoral vein forms the lateral border, the lacunar ligament forms the medial border and the fascia over pectineus muscle forms the posterior border. The neck of the femoral canal is narrow and An inguinal hernia always originates superior to the inguinal canal at a variable point along its length depending on whether the hernia is direct or indirect. The end point of the inguinal canal is the pubic tubercle, and a femoral hernia always originates infero-medially to this. Hence if the point of origin can be found, defining the surface anatomy of the inguinal canal and the pubic tubercle are key steps in differentiating these two types of hernia. It is often stated that inguinal hernias originate superior-medial to the pubic tubercle, as this is where the superficial ring is. Whilst this is often the case, inguinal hernias do not always exit via the superficial ring, so this is not always true. However, inguinal hernias always originate above the inguinal ligament. Finding the public tubercle and inguinal ligament is therefore the key step in clinical examination of the groin. Clinical presentation and management Hernias usually present as a unilateral lump but they may present with the symptoms of obstruction or strangulation (for definitions of these terms see Table 2). Complications of hernias are often medical emergencies which are beyond the scope of this article. Here we will focus on the non-emergency presentation of a unilateral groin lump. This article will focus on the examination of hernias which are non-tender and non-obstructed at presentation. See 34 Table 3 for descriptive terminology applied to hernias. Figure 4 Palpating the deep ring at the midpoint of the left inguinal ligament Examination Figure 3 (a) Schematic demonstrating the difference between the midpoint of the inguinal ligament and the mid-inguinal point. Preparation Introduce yourself to the patient and confirm their identity. Wash your hands and put on a pair of gloves (gloves are not necessary but you may prefer to wear them). The entire groin and waist must be exposed for an adequate examination – see Figure 6. This may cause embarrassment so try to minimise the duration and the extent of exposure of the genitalia. Allow the patient privacy to undress and provide gowns and sheets if required. Ask the patient to lie as flat as possible on an examination couch with a pillow behind the head for comfort. This positioning of the patient facilitates easy inspection by ensuring that the groins are not creased and also reduces intra-abdominal pressure allowing reducibility/irreducibility of hernias to be demonstrated. Ensure the patient is comfortable, check they do not have any pain and take informed consent. Figure 3 (b) Identifying the right inguinal ligament by palpating the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine. Literature Search We searched the literature with the ‘Diagnosis’ option of PubMed’s Clinical Queries feature, using all appropriate MeSH terms (hernia; hernia, inguinal; hernia, femoral; hernia, abdominal). We searched a selection of standard European and American textbooks, including specialised evidence-based texts [3,4]. We also searched specific web based resources [5,6] and relevant journals (Hernia and Evidence Based Medicine) [7,8]. No clinical prediction rules were identified. Figure 5 The anatomy of the right femoral canal Lying or Standing? 35 There is no consensus in the literature on the whether the patient should be examined standing, supine or both. The supine position allows subsequent examination of the abdomen and is more comfortable for both the patient and the examiner. Although a hernia will often be more obvious in the standing position, a satisfactory examination in the supine position will obviate the need for standing examination. We therefore recommend starting with the patient supine. Figure 7 A healed incision from a previous open inguinal hernia repair operation. The scar is now barely visible and may easily be missed on first inspection. Figure 6 The correct positioning of the patient for supine examination of a hernia. Note the use of a towel to preserve patient dignity while achieving adequate exposure. Examination routine Examination of a hernia has much overlap with the generic Examination of Lumps and Bumps [9] and as with all examinations proceeds in the following sequence: inspection, palpation, auscultation followed by special tests. It is often helpful to compare the side with the suspected hernia to the contralateral side because a ‘normal’ groin is difficult to define and asymmetry is an important indicator of unilateral pathology. However, beware that groin hernias can be bilateral and so symmetry does not necessarily mean that both sides are normal. Inspection Inspect the groin for lumps and look for scars in the inguinal region from previous operations - see Figure 7. Concentrate particularly on the area at the medial end of the groin crease. Ask the patient to cough (ask the patient to turn away first to avoid them coughing on you) and then to lift their head off the bed. These actions raise the intra-abdominal pressure which may cause hernias to appear or become more prominent. Try to make a judgement about the site of the lump, its size, its shape, the condition of the overlying skin, and whether or not it appears to descend into the scrotum. Palpation You will already have an impression of the characteristics of the lump from your inspection. Confirm the site, size and shape of the lump as well as the relationship of the lump to underlying structures. As already explained, it is particularly important to relate the site to the public tubercle and the inguinal ligament. Try to define characteristics of the surface and edge of the lump. Examine the lump for consistency including fluctuance, compressibility, pulsation and transillumination. Table 4 summarises the key features of the differential diagnoses. If the lump descends into the scrotum it is necessary to differentiate it from scrotal pathology by attempting to ‘get above’ it. If the testes can be felt separately, then the lump is unlikely to be scrotal in origin. Please see The JCE Expert Review: Examination of the male external genitalia [10]. The cough test The cough test should be performed during the palpation section of the examination. The tips of the examiner’s fingers should be placed over the lump. The patient is then asked to cough (turning away from the examiner to do this) - see Figure 8. If the lump expands on raising the intra-abdominal pressure in this way, the lump is said to be expansile. This indicates that the pressure wave is being transmitted through the abdominal wall to increase the size of the lump, and therefore that a hernia is likely. It is important to note that this is different from a transmitted non-expansile cough impulse, which is sometimes present in the absence of a hernia. 36 be less likely to cause pain. Successful reduction may be accompanied by a ‘squelch’ (indicating that the hernia contains bowel) and confirms the diagnosis of a hernia. If it is not possible to reduce the hernia then, by definition, this is an irreducible hernia. Figure 8 Performing the cough test. Here the examiner is palpating a suspected inguinal hernia. Auscultation Auscultate the hernia for bowel sounds with a stethoscope. The interpretation of this test is subjective, and it is generally considered to be of low sensitivity and specificity, although there is little evidence in this area. The presence of bowel sounds confirms the presence of a bowel loop with ongoing peristalsis. The absence of bowel sounds is non-specific and requires more interpretation. The most obvious explanation is that the hernia does not contain a loop of bowel. However, bowel sounds will also not be present in strangulated hernias because of the failure of peristalsis. Reduction If a hernia is diagnosed then attempts should be made to reduce it back into the abdominal cavity. Should the hernia be very tender to palpation or irreducible, urgent general surgery consultation is required. It is easiest to reduce groin hernias with the patient lying flat in the supine position. Using both hands, with the pulps of the fingers surrounding the neck of the hernia, the proximal part should be guided by slow gentle pressure through the fascial defect aiming to move it from outside to inside the abdominal cavity. If examination/manipulation of the hernia at any stage is painful then the examination should stop. In difficult cases a “Trendelenburg tilt”, in which the patient is positioned supine at 20 degrees with their head down, may aid reduction. Analgesia (to relax the abdominal wall musculature), or a cold compress (to reduce oedema) can also be used but should be allowed adequate time to work. Excessive pressure on the apex of the hernia can cause it to mushroom around the abdominal wall defect, impeding reduction. Asking the patient to reduce the hernia himself is an alternative and may Once the hernia is reduced it is important to try to differentiate between femoral and inguinal hernias as the former are at higher risk of strangulation (see Table 5). This is achieved by applying pressure over the suspected origin of the hernia and then increasing intra-abdominal pressure to see if the hernia remains reduced. Classically an inguinal hernia is said to lie above and medial to the pubic tubercle, whereas a femoral hernia lies lateral and below. However, as discussed above, this is not always the case. To identify a femoral hernia, Hair et al. suggest applying pressure over the femoral canal. This can be achieved either by following adductor longus tendon to below the inguinal ligament and then placing a finger anterior and lateral to the tendon, or by palpating the femoral artery and placing a finger approximately a finger breath medial to it. These manoeuvres should obstruct the femoral canal and hence a femoral hernia should remain reduced, while an inguinal hernia will re-appear as an obvious swelling when the patient is asked to cough[11]. Differentiating between direct and indirect inguinal hernia has less clinical significance and current data suggests that the accuracy of doing so is poor, EB2, but none the less the question often arises in medical finals and post-graduate examination and candidates should use this opportunity to demonstrate their understanding of the relevant anatomy and pathology. First, with the hernia reduced, locate and apply pressure over the internal inguinal ring at the midpoint of the inguinal ligament and ask the patient to cough. If this manoeuvre prevents the hernia reappearing, the hernia is said to be indirect. If this fails, apply pressure over Hesselbach’s triangle and ask the patient to cough. If this prevents reappearance, the hernia is then said to be direct (see Figure 9). If the hernia does not reappear, ask the patient to stand and repeat both tests. Inguinoscrotal hernias are almost always indirect. See Table 6. 37 rectus muscles. In medical school and postgraduate examinations you should indicate to the examiner any additional examinations you would like to perform and he may or may not ask you to proceed. Finally thank the patient, help them dress and wash your hands. Acknowledgements Many thanks to Professor Paul Glasziou and Jo Hunter for their advice with literature searches. Thanks to Miss M Weisters for her help. Conflicts of Interest None declared Figure 9 Hesselbach’s triangle Examination in the Standing Position As previously noted there is no consensus on the whether the patient should be examined standing, supine or both. The routine above describes the examination with the patient supine, however some hernias spontaneously reduce in this position and are only clinically detectable when the patient is standing. The authors recommend starting the examination with the patient in the supine position but if no groin mass is identified, or examination is inconclusive, then the examination should be performed with the patient standing. Ask the patient to stand, exposed below the waist. Sit or crouch facing the patient with your eyes at waist height. Inspect, palpate, auscultate and attempt to reduce any mass as previously described. The examination is technically more difficult with the patient in the standing position, but often makes the identification (but not reduction) of hernias easier due to the effects of gravity. Examination then proceeds in the same way as the supine examination. To Complete the Examination In addition to the core examination described above it may be necessary to examine the contralateral groin for a hernia and also to examine the abdomen. See The JCE Expert Review: Examination of the Gastrointestinal System [17]. A hernia on either side is a risk factor for a hernia on the contralateral side so a thorough examination should always include both groins. Examination of a hernia may also reveal pathology in the abdomen such as abdominal wall hernias or divarication of the 38 References [1] Jopling H, The principles of Clinical Examination. The Journal Of Clinical Examination, 2006; 1: 3-6 [2] Henry M, T. J. Clinical Surgery. 2nd edition. Saunders 2004 [3] Sapira. Sapira's Art and Science of Bedside Diagnosis. 3rd edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2005 [4] McGee. Evidence Based Physical Diagnosis. 2nd edition. Saunders 2007 [5] Clinical Evidence, BMJ ClinicalEvidence.com [6] Up to Date, Wolters Kluwer UptoDate.com [7] Hernia; The World Journal of Abdominal Wall Surgery, Springer http://www.springer.com/medicine/surgery/journal/1 0029 [8] Evidence Based http://ebm.bmj.com/ Medicine, BMJ Nyhus classification of inguinal hernias and typerelated individual hernia repair. A case for diagnostic laparoscopy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 7(5): 373-7 [13] Kraft BM, K. H., Kuckuk B, Haaga S, Leibl BJ, Kraft K, Bittner R. Diagnosis and classification of inguinal hernias. Surg Endosc; 2005; 17(12): 20214 [14] Van den Berg JC, d. V. J., Go PM, Rosenbusch G. Detection of groin hernia with physical examination, ultrasound, and MRI compared with laparoscopic findings. Invest Radiol (1999); 34(12): 739-43 [15] Novitsky YW, C. D., Kercher KW, Kaban GK, Gallagher KA, Kelly JJ, Heniford BT, Litwin DE. Advantages of laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal herniorrhaphy in the evaluation and management of inguinal hernias. Am J Surg 2007; 193(4): 466-70 [9] Carey, J., Mortensen N. Examination of lumps and bumps. The journal of Clinical Examination 2008; 6: 12-17 [16] Black J, T. W., Burnand K, Browse N. Browse's Introduction to the Symptoms and Signs of Surgical Disease. 4th edition. Hodder Arnold 2005 [10] Examination of the male external genitalia The Journal of Clinical Examination 2011; 11: 22-31 [17] Gardner, A. Examination of the Gastrointestinal System. The Journal of Clinical Examination 2006; 1:7-11 [11] Hair A, Paterson & O’Dwyer Diagnosis of a femoral hernia in the elective setting. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh (2001) 46:117-18 [12] Renzulli P, F. E., Schäfer M, Werlen S, Wegmüller H, Krähenbühl L. (1997). Preoperative 39 Hernia type Description Inguinal Femoral Epigastric Caused by a weakness in the inguinal canal. Relative incidence 78%. Caused by a weakness in the femoral canal. Relative incidence 7%. Caused by the weakness in the epigastric linea alba, between the umbilicus and the xiphisternum. Relative incidence 1%. Caused by the weakness in the obturator canal in the thigh. Mostly discovered at laparotomy for strangulation. Caused by weakness around the umbilical scar in adults, displacing the umbilicus to one side. High risk of obstruction and strangulation. Caused by weakness in wounds after abdominal operations (relative incidence 35%). Most often in mid–line vertical incisions. Risks factors are wound infection, obesity and poor surgical technique. Strangulation is rare. Relative incidence 10%. Caused by a weakness in linea semiluminaris, at the lateral border of rectus abdominis. High risk of strangulation. Only occurs in infants through the congenital weakness at the umbilicus. Most spontaneously resolve. Relative incidence 3%. Obturator Paraumbilical Incisional Spigelian Umbilical Table 1: Types of abdominal and groin hernias [2]. Relative incidence is the incidence of each particular type of hernia relative to all abdominal wall hernias. Complication Irreducible Strangulated Obstructed Definition The hernial contents cannot be returned to the bowel. This is either due to adhesions or a narrow hernial neck. The blood supply to the contents of the hernia e.g. bowel or omentum is compromised. Venous occlusion followed eventually by arterial occlusion results in ischemia/infarction. This is a surgical emergency. The bowel lumen within the hernia sac becomes obstructed with typical clinical features of pain, vomiting diarrhoea or constipation. This is a surgical emergency. If the loop is closed, this will proceed to strangulation. Table 2: The complications of abdominal and groin hernias. Terminology Richter’s hernia Maydyl’s hernia Pantaloon hernia Sliding hernia Definition The antimesenteric border of the bowel herniates through the abdominal wall defect. Can result in strangulation and necrosis without obstruction. Also called ‘hernia en W’, the ‘W’ shaped loop of bowel results in an intra-abdominal segment (the middle of the loop), which is the strangulated segment Indirect and direct hernia are found together Part of the wall of the sac is formed by a viscus e.g. bladder or large bowel Table 3: Special types of hernia. 40 Differential Diagnosis of Groin Lumps Inguinal/femoral hernia Saphena Varix Ectopc/undescended testes Femoral artery aneurysm Lymph node Hydrocoele of the cord Lipoma of the cord Characteristics See table 5 Mass at the junction of the long-saphenous vein and femoral vein (2cm infero-medial to the femoral artery) caused by an incompetent valve. Expansile mass with a cough impulse and a thrill on distal percussion. Often has a bluish tinge. Often a mass in the external ring. Underdeveloped hemi-scrotum. Expansile mass along the course of the femoral artery (runs through mid point of the inguinal line). No cough impulse, non reducible, firm mass No cough impulse, fluctuates and transilluminates Soft mass, able to get above, does not transilluminate or fluctuate Table 4: Differential diagnosis of a scrotal groin lump. Femoral Reduces to a point infero-lateral to the pubic tubercle Often irreducible Often presents with strangulation Small Inguinal Reduces to a point superio-medial to the pubic tubercle Mostly reducible Mostly presents with asymptomatic mass Can be large Table 5: Distinguishing features of femoral and inguinal hernias. Indirect Can descend into scrotum Reduces upwards, laterally and backwards Controlled by pressure over the internal ring Defect not palpable (behind fibres of external oblique) After reduction, the bulge appears at the middle of the inguinal canal then flows medially Direct Does not descend into scrotum Reduces upwards, and straight backwards Not controlled by pressure over the internal ring Defect may be palpable After reduction, the bulge appears exactly where it was before Table 6: Distinguishing features of direct and indirect hernias. From The Symptoms and Signs of Surgical Disease [16]. 41 Four studies [12-15] have looked at the accuracy (sensitivity and specificity) of clinical diagnosis of inguinal hernias. The methods and results are summarised in the table below. None of these studies quantified kappa. All four studies looked at populations of patients referred to hospital by general practitioners with a clinical diagnosis of inguinal hernia. The majority of these patients had a unilateral hernia. However, some patients had clinically evident bilateral hernias at presentation and were referred for management of both sides (for example, Renuzulli et al [12] looked at 30 patients who were referred with 35 hernias i.e. 5 of the patients had bilateral clinically evident disease). The studies compared findings at clinical examination for both sides to those at laproscopic surgery for both inguinal regions (in most cases this meant one clinically abnormal groin and one normal groin). The procedure used was transabdominal preperitoneal laparoscopic repair. This procedure allowed an anatomical examination from within the abdomen of both inguinal regions, even if only one groin was repaired. It was the gold standard for accurate anatomical diagnosis of both groins. This methodology as was used so that clinically normal groins could have a definitive anatomical diagnosis, and hence the true negative and false negative rates of clinical examination could be collected (in addition to the true positive/false positive rates at the clinically positive side). Hence examining both sides allowed both sensitivity and specificity to be calculated. The results are shown in the table below. Authors Ref Population n Incidence* Sensitivity Specificity Renuzulli et al [12] 30 0.47 0.96 0.43 Kraft et al [13] 220 0.66 0.92 0.64 Van den Berg et al [14] 41 0.67 0.75 0.96 Novitsky et al [15] 30 patients (with 35 suspected groin hernias) referred for surgical management of probable inguinal hernia. 220 patients (with 274 suspected groin hernias) referred for surgical management of probable inguinal hernia. 41 patients referred for surgical management of clinically evident inguinal hernias. 262 patients (with 283 suspected groin hernias) referred for surgical management of probable inguinal hernia. 262 0.54 0.95 0.80 *Incidence quoted is the total number of inguinal hernias found at surgery divided by the total number of groins examined i.e. this is a measure of incidence per groin, whether clinically evident or not. In summary, the sensitivity of clinical diagnosis of inguinal hernia is 0.75 - 0.96 and the specificity of clinical diagnosis of inguinal hernias is 0.43 - 0.96. These are relatively wide ranges and more data is required to draw confident conclusions but it suggests that clinical examination is relatively powerful for detecting and excluding the presence of an inguinal hernia. Evidence Box 1: Diagnosing Inguinal Hernias 42 Two studies looked at the accuracy of differentiating direct from indirect hernias. In these studies the examining clinician stated pre-operatively whether he/she thought the clinically evident inguinal hernia was direct or indirect. This was compared with the findings at laparoscopic repair, which again provided a definitive clinical diagnosis. The clinically normal side was not part of this analysis. In one study [12], the sensitivity of detecting a direct inguinal hernia in a population of inguinal hernias was 0.71 and the specificity was 0.57. In the other study [13], the ‘accuracy’ of differentiating direct from indirect hernias is given as 0.54. The authors define ‘accuracy’ as the proportion of positive concurrences (i.e. the authors do not give the data in the traditional sensitivity/specificity format, and do not provide the raw data for its calculation). In summary, there are no high quality studies addressing this question, but the current data suggests that the accuracy of differentiating direct from indirect hernias is poor. In medical finals and post-graduate examination candidates are often asked to distinguish direct and indirect inguinal hernias by clinical examination. Candidates should be aware that this examination is likely to have very little discriminating value but a proper explanation of the traditional account allows them to demonstrate their understanding of the relevant anatomy and pathology. Evidence Box 2: Differentiating Direct from Indirect Inguinal Hernias 43