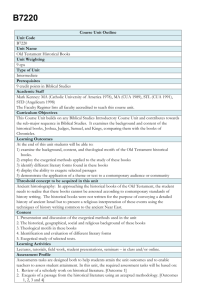

JESOT 2.1 () - Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old

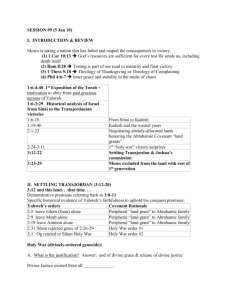

advertisement