HYPNOTICALLY REFRESHED TESTIMONY AND ITS

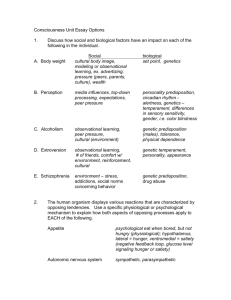

advertisement