ambiguity. - Brainstorm Services

advertisement

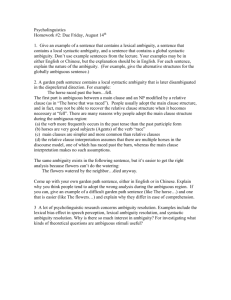

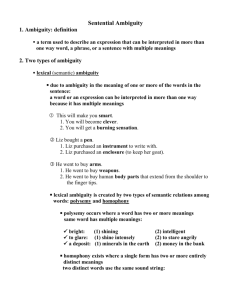

AMBIGUITY AMBIGUITY: A word, phrase, sentence, or other communication is called ambiguous if it can be interpreted in more than one way. Ambiguity is distinct from vagueness, which arises when the boundaries of meaning are indistinct. -Wikipedia.org Above are a few classic examples of perceptual “ambiguity.” Depending on your view, you might see an old woman or a young woman, a face or the back of someone wearing a parka. Which do you see first? How long before you can see more than one image? How do you decide which “interpretation” of these ink marks is the “correct” one? The online glossary for the Compact Bedford Introduction to Literature defines ambiguity in a literary context as follows: “[Ambiguity] allows for two or more simultaneous interpretations of a word, phrase, action, or situation, all of which can be supported by the context of a work. Deliberate ambiguity can contribute to the effectiveness and richness of a work.... However, unintentional ambiguity obscures meaning and can confuse readers.” Hopefully these terms—“deliberate” and “unintentional”—aren’t themselves a little misleading. Creative writers probably aren’t “deliberately” ambiguous; beauty and ambiguity end up being the byproducts of an artist’s power with words. Just as a writer is not “deliberately ambiguous,” only a weak piece of writing would be “unintentionally ambiguous.” Meyer helps us understand here that literary ambiguity means more than “vague” or “imprecise,” or “unclear.” It means just the opposite. Ambiguity suggests the potential for many meanings, all of them equally clear and perceptible to the reader. Nonfiction writers do not strive for or tolerate ambiguity; the aim in nonfiction is to make one’s point unambiguous and unequivocal. Nonfiction writers hope that any two readers approaching their text would come away with the same understanding of it. On the contrary, imaginative literature may be called “richly ambiguous” in the sense that it supports differing “interpretations” (meanings). Two readers can experience the same work in different ways, pull different ideas, emotions, memories from it; they can pursue differing associative meanings. Some readers may even develop highly personal interpretations in the sense that no one else reading the same work would be likely to choose to interpret it quite the same way. Although the knee-jerk tendency in such a case might be to declare those interpretations “wrong,” it’s more appropriate (and way more interesting) to acknowledge that no interpretation can be completely “wrong.” We make meaning from a work of literature in highly personal, sometimes highly eccentric ways. And even these eccentric interpretations have a place; they’re valuable at least to the person who makes them. The way you choose to interpret something is a key part of the deep enjoyment you get from reading. What could be worse than someone telling you your feeling about a character is “wrong”? That would destroy your experience of the work, not add to it. Sometimes people agree, sometimes they don’t. In my view, and in the view of reader response critics generally, there are no “wrong” interpretations, any more than it would be appropriate to say of the above picture that people who see the old woman are “wrong.” Great literature is open to interpretation; it’s ambiguous.