Stopping Porta-Nukes Christopher Helman, Forbes Magazine, 12.24

advertisement

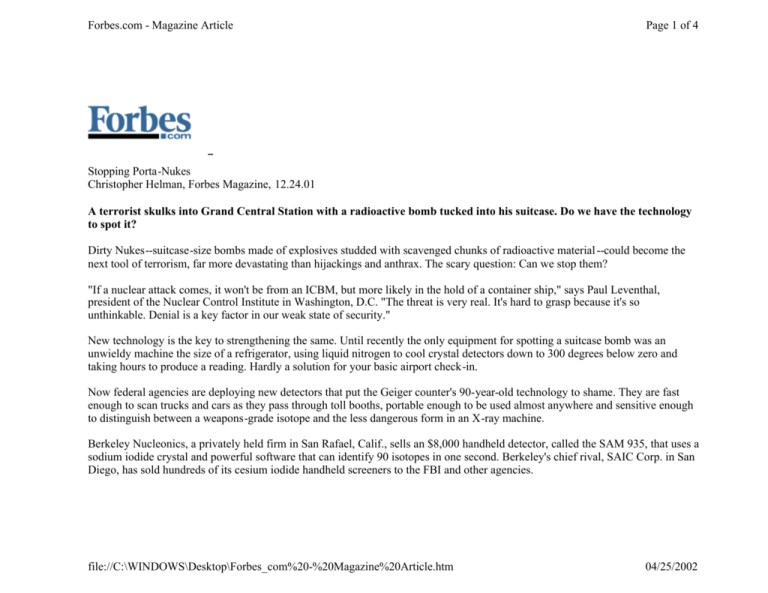

Forbes.com - Magazine Article Page 1 of 4 Stopping Porta-Nukes Christopher Helman, Forbes Magazine, 12.24.01 A terrorist skulks into Grand Central Station with a radioactive bomb tucked into his suitcase. Do we have the technology to spot it? Dirty Nukes--suitcase-size bombs made of explosives studded with scavenged chunks of radioactive material --could become the next tool of terrorism, far more devastating than hijackings and anthrax. The scary question: Can we stop them? "If a nuclear attack comes, it won't be from an ICBM, but more likely in the hold of a container ship," says Paul Leventhal, president of the Nuclear Control Institute in Washington, D.C. "The threat is very real. It's hard to grasp because it's so unthinkable. Denial is a key factor in our weak state of security." New technology is the key to strengthening the same. Until recently the only equipment for spotting a suitcase bomb was an unwieldy machine the size of a refrigerator, using liquid nitrogen to cool crystal detectors down to 300 degrees below zero and taking hours to produce a reading. Hardly a solution for your basic airport check-in. Now federal agencies are deploying new detectors that put the Geiger counter's 90-year-old technology to shame. They are fast enough to scan trucks and cars as they pass through toll booths, portable enough to be used almost anywhere and sensitive enough to distinguish between a weapons-grade isotope and the less dangerous form in an X-ray machine. Berkeley Nucleonics, a privately held firm in San Rafael, Calif., sells an $8,000 handheld detector, called the SAM 935, that uses a sodium iodide crystal and powerful software that can identify 90 isotopes in one second. Berkeley's chief rival, SAIC Corp. in San Diego, has sold hundreds of its cesium iodide handheld screeners to the FBI and other agencies. file://C:\WINDOWS\Desktop\Forbes_com%20-%20Magazine%20Article.htm 04/25/2002 Forbes.com - Magazine Article Page 2 of 4 SAIC also makes larger "portal" detectors that look like the metal detectors at airports. Packed into two 65-pound suitcases, these $10,000 snoopers also use sodium iodide crystals to spot radiation on individuals, but they can't discern among isotopes. That requires a scan with a more precise handheld device. "This time next year there will be hundreds of these used at critical points across the U.S.," says James Winso, an SAIC director. Government agencies have spent an estimated $100 million on detection gear this year, says Ralph James, a research director at Brookhaven National Laboratory. The market could double in three years, speculates David Brown, president of Berkeley Nucleonics: "Instead of selling 10 units at a time, we're now selling devices in quantities of 100." But signs of the growing risk occurred long before Sept. 11. Since 1993 nearly 400 cases of illegal trafficking in nuclear and radioactive materials have been tracked by the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna. In 18 instances small amounts of bomb-grade uranium or plutonium were involved. In July four men were arrested in Georgia, the former Soviet republic, on a charge of plotting to sell 4 pounds of enriched uranium 235; it takes 55 pounds of it to build a bomb. Customs agents carry basic Geiger-counter-like devices in their shirt pockets to measure radiation exposure. But while the Geiger counter spots radiation easily, it can't determine which isotope is present, and therefore is unable to tell whether danger is at hand. Geiger counters use an electrically charged wire inside a metal tube filled with methane and argongas. A window at one end lets in ionizing radiation from a decaying isotope. The radiation ionizes an atom in the gas mixture, setting off a cascade of electrons that hit the wire and register as an electric pulse counted by a meter or amplified into the familiar "click-click-click." The newer detectors forgo wires and gas in favor of highly engineered crystals made from sodium iodide or cesium iodide. These ice-cube-size crystals are grown slowly in ovens heated as high as 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, adding just one centimeter in a day. They are so dense they can absorb radiation entirely. When exposed to an isotope, the crystals flash for 50 billionths of a second. Since every isotope that spews gamma or X rays or charged particles does so in a unique way--an atomic fingerprint, of sorts--the color and intensity of the flash tells the detector which isotope is present and in what quantity. Berkeley Nucleonics' SAM 935, introduced in 1995 and upgraded annually, looks like a big can of shaving cream, with a crystal positioned inside the opening at one end. Once an isotope causes the crystal to flash, a photosensitive cathode releases electrons into a vacuum tube where a chain reaction produces a cascade, as in the Geiger counter. Resulting electrical pulses are analyzed by file://C:\WINDOWS\Desktop\Forbes_com%20-%20Magazine%20Article.htm 04/25/2002 Forbes.com - Magazine Article Page 3 of 4 software that can determine on the fly which isotopes are present. Founded in 1960, Berkeley Nucleonics has annual sales of less than $50 million, peddling measurement devices to the nuclear and chemical industries. It has sold hundreds of the new detector units to the military, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy and emergency response teams. Terrorists could find a way around some of these scanners--for example, by lining a suitcase with lead. SAIC and Berkeley Nucleonics can respond with additional detectors that pick up neutrons. In the end nuclear security comes down to a battle of brainpower. Says SAIC's Winso: "A lot of these terrorists have fine German and American engineering educations. They're smart people." Let's hope our guys are smarter. file://C:\WINDOWS\Desktop\Forbes_com%20-%20Magazine%20Article.htm 04/25/2002 Forbes.com - Magazine Article Page 4 of 4 file://C:\WINDOWS\Desktop\Forbes_com%20-%20Magazine%20Article.htm 04/25/2002